With the COVID-19 virus spreading at an aggressive rate, causing widespread disruption and threatening a global recession, central banks around the world are racing to cut interest rates to zero in an attempt to allay the economic impact.

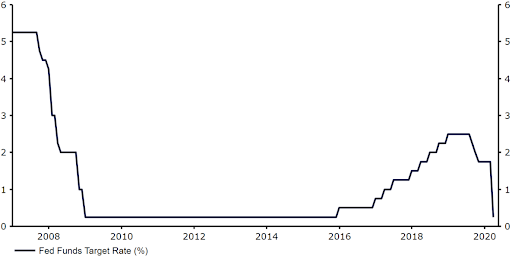

Figure 1: Fed Funds Target Rate (2007 – 2020)

In addition to the aforementioned rate cut, the FOMC also unveiled a host of other sweeping measures designed to support the US economy, unleashing many of the tools it used in ‘08. The bank’s quantitative easing programme was relaunched. Under the programme, the Fed will buy $700 billion worth of assets in the coming weeks, $500 billion of which will be US Treasuries, with the rest made up of mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Moreover, the Fed’s discount window, the interest rate on loans for commercial banks that require emergency lending, was cut. This rate was lowered by 125 basis points to 0.25%, with the term of the loans to be extended from overnight to 90 days. Reserve requirements for some banks were cut to zero, while the Fed also announced cooperation on dollar-swap lines with other central banks. These latter moves should help ease the liquidity tensions that were apparent in markets late last week.

Given the severity of the situation, Sunday’s bazooka of a stimulus announcement is not a major surprise – we were already pencilling in a 100 basis point move at the bank’s scheduled meeting this week. Since the 3rd March rate cut, the number of confirmed cases of the virus has continued to increase at an accelerated rate, up from 12,746 outside of China to 88,717 and from 124 to 3,680 in the US alone*. This ensures that more than 50% of the total cases of coronavirus have now been reported outside China. US equity markets have also continued to sell-off sharply despite the initial 50 basis point rate cut, as they have done around the world. The Dow Jones and S&P 500 indices are currently trading approximately 30% lower since mid-February (Figure 2), moves reminiscent of the great crash of ‘08.

Figure 2: S&P 500 and Dow Jones Indices (February ‘20 – March ‘20), In light of the dramatic sell-off in US equity markets and the global recession that we think the virus is set to trigger, a cut to zero is entirely justified, in our view. Other central banks have followed suit in the past few weeks, with the Bank of England, Bank of Canada and European Central Bank, to name but a few, all either cutting rates or announcing more unconventional measures designed to support their domestic economies. We think that those central banks that have room to continue cutting rates to zero will now do so, accompanied with additional injections of stimulus where possible. A combination of extremely low rates, bank forbearance and fiscal stimulus is a powerful antidote to the economic and financial consequences of the pandemic.

The issue for the Federal Reserve is that it has now almost exhausted the more conventional tools available at its disposal. There is certainly no appetite among the FOMC to lower rates into negative territory. According to Chair Powell, the Fed ‘do not see negative policy rates as likely to be an appropriate policy response here in the United States’. We think that the bank will therefore focus more on pumping liquidity into the sectors of the US economy that are most exposed to the crisis. This may involve expanding its QE programme to riskier assets, including corporate bonds or even stocks.

The reaction among currency traders to the Fed’s announcement was to send the US dollar lower, down around 1% versus the euro during Asian trading. For now, however, the dollar is continuing to be viewed as the safe-haven of choice, having rallied sharply against almost every other currency last week (Figure 3). We think that this could remain the case in the immediate-term as investors continue to favour the greenback due to its role as the world’s most liquid currency. The US is also less-dependent on external demand than its safe-haven peers, while the spread of the virus there appears to be less aggressive than in the Euro Area, although this is likely to be at least partly due to a lack of testing. The absence of a historical precedent for the current situation does, however, ensure that predicting currency moves in both the short- and long-term is incredibly difficult.

Figure 3: EUR/USD (09/03/20 – 16/03/20)