G3 Forecast Revision – January 2021

- Go back to blog home

- Latest

News headlines out of the foreign exchange market have continued to be dominated by the latest developments surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic in the past few weeks.

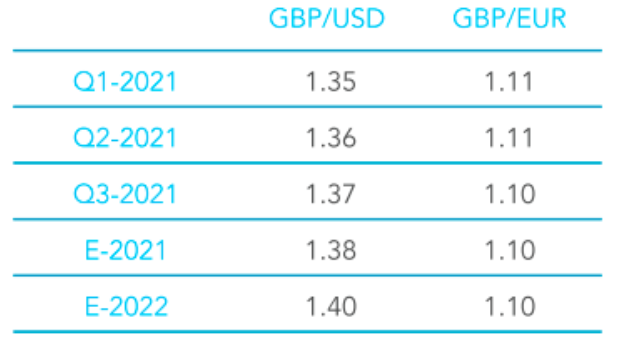

As a result, case numbers and deaths caused by the virus in the US have surged to record highs, while the same measures in most of Europe have either stabilised or fallen to multi-week lows (Figure 1). An exception to this is the UK, where the more aggressive spreading strain of the virus has caused caseloads to spiral sharply higher since the beginning of December, leading to the reimposition of further strict lockdowns in Britain in early-January.

Figure 1: G3 New COVID-19 Cases [per 1M people] (March ‘20 – Jan ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 06/01/2021

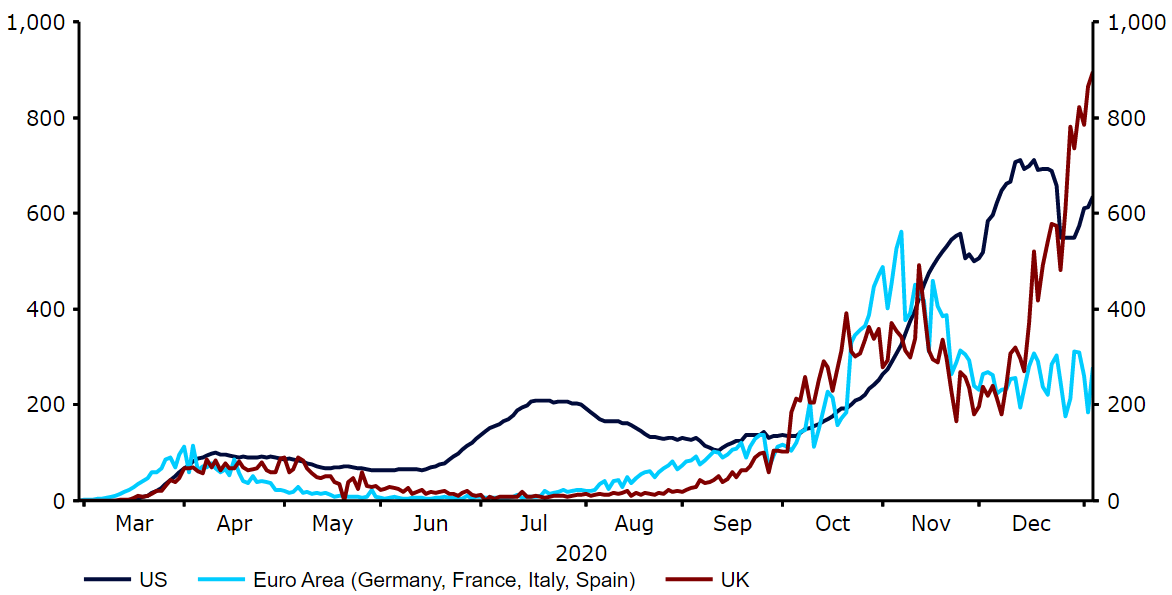

The tough virus restrictions put in place during the fourth quarter have also once again weighed on economic activity. Most major economic areas around the world bounced back strongly in Q3, posting record expansions as containment measures were gradually unwound. It does, however, look likely that both the Euro Area and the UK economy suffered from contractions once again in Q4, with overall activity still well below pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2).

Figure 2: GDP (US, Euro Area & UK) [Q1 2020=100] (2014 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 06/01/2021

That being said, encouraging news of progress towards multiple COVID-19 vaccines has buoyed financial markets and raised hopes that a return to normalcy could take place sooner than had previously been anticipated. The UK was the first country in the world to begin mass vaccinations using the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine on 8th December, with vaccinations using the AstraZeneca jab commencing in early-January. The US also began its vaccination programme in December, with the EU not too far behind. Risk assets have rallied sharply on the news with the safe-havens, including the US dollar, falling markedly. We think that news of progress towards the mass rolling out of vaccines among the developed nations will be one of the main drivers for the G3 currencies in 2021.

US Dollar (USD)

The US dollar was on the back foot against most of its major peers throughout much of the final quarter of 2020.

Investors had flocked to the dollar during the worst of the market panic earlier in the year. The currency jumped to its strongest position against its major peers in over three years at the end of March, although these safe-haven bets were reversed in the second and third quarters. Since the beginning of the fourth quarter, the dollar has been back under selling pressure again as markets cheered both the outcome of the US presidential election and news of progress towards multiple COVID-19 vaccines. The US dollar index is currently trading around its lowest level since April 2018 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: US Dollar Index (January ‘20 – January ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

November’s presidential election was perhaps the biggest event risk in financial markets in the past few months, outside the COVID pandemic. Investors had a case of deja vu on the night of the election, as early results suggested that Trump had once again outperformed the opinion polls. With the vast majority of mail-in votes cast by Democrats it did, however, become increasingly clear that Biden was heading for victory fairly early on, even though the final outcome in a handful of states was not known until a few days after election night. Investors ditched the safe-haven dollar and favoured risky assets long before the final result was officially adjudicated. A Biden presidency has been perceived as a positive for risk assets and negative for the safe-haven US dollar, given the likelihood of a larger fiscal stimulus programme and decreased trade uncertainty under a Democratic administration.

An issue for Biden at the time was that the Democrats were unable to win control of the Senate and achieve a so-called ‘blue wave’. Two run-off Senate elections in Georgia on 5th January took on an unusual amount of significance and were closely watched by financial markets. The Democrats required a double-win in order to obtain full control of Congress, thus granting Biden a much better chance of passing legislative changes once he takes office later this month. In the end, the Democrats surprised our and indeed the markets’ expectations in winning both votes. So far, currencies have reacted as we anticipated that they would in such a scenario, with the dollar selling off across the board. We think that the dollar could come under a bit of additional selling pressure in the short-term, as investors continue to price in larger fiscal support from the Biden administration.

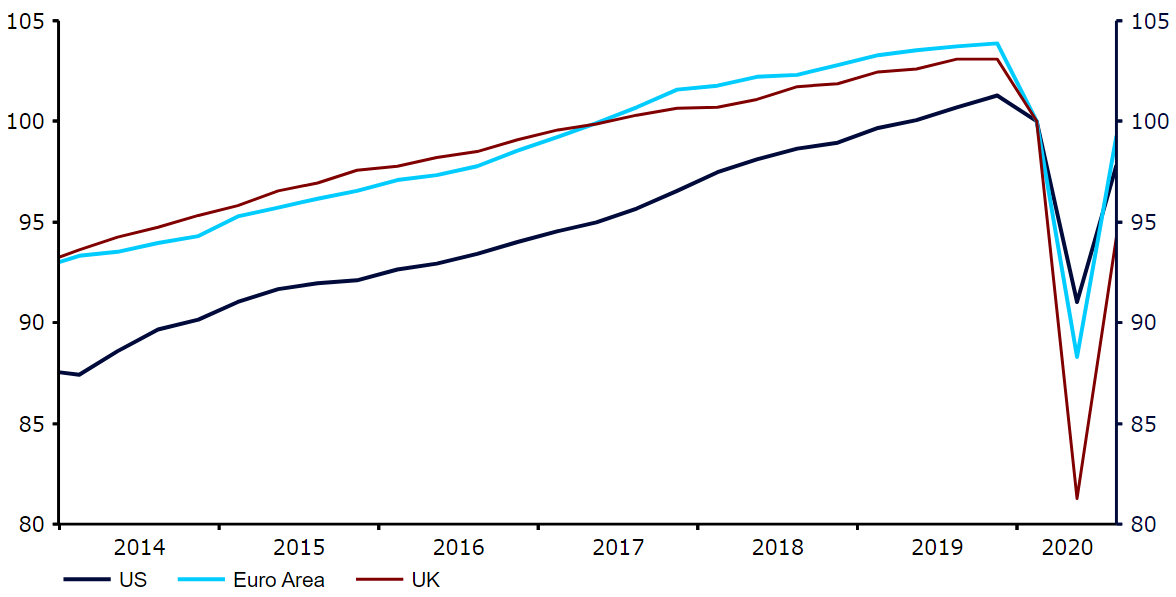

One of the most contentious issues leading up to the election was President Trump’s handling of the ongoing pandemic. Since our last G3 update, the virus situation has worsened in the US, as it has done throughout much of the developed world. New daily cases have jumped to record highs (Figure 4), as have deaths caused by the virus. According to Worldometer, the US now has one of the top fifteen worst COVID death rates in the world (more than 1,100 per 1 million people) and a cases per capita ratio that far outstrips most other developed nations (approximately 65,000 per 1M).

Figure 4: New Daily COVID-19 Cases [US] [per 1M people] (March ‘20 – Jan ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

Action from US authorities in response to the recent sharp increase in confirmed virus cases has, however, been slower than that seen in almost all of Europe. There has been no national lockdown and the state level responses that we have seen has, for the most part, been subdued compared to the more draconian measures enforced in the European continent. So far, this light touch approach means that the US economy has rebounded better from the sharp downturn experienced in the second quarter of the year. Third-quarter growth of 33.1 % annualised was comfortably the fastest expansion on record, aided by a jump in domestic consumption and strong gains in investment and export growth.

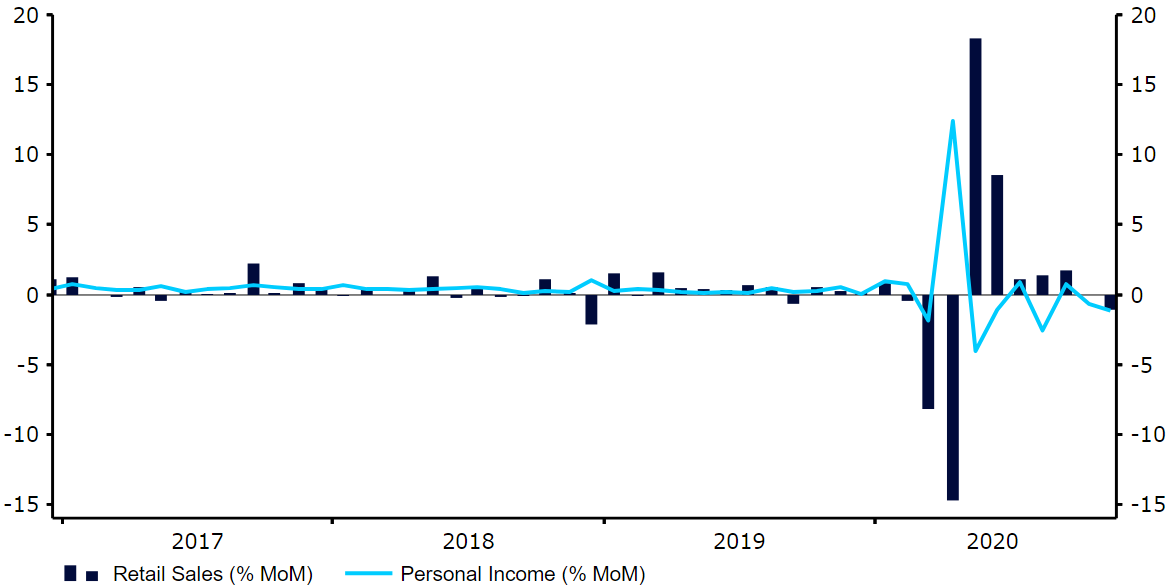

Advance indicators of business activity covering the Q4 period have also painted a fairly rosy picture. The latest business activity PMIs have continued to trend higher and have diverged from their European equivalents. The non-manufacturing PMI from ISM has remained comfortably in expansionary territory, despite easing slightly to 55.9 in November. November’s composite PMI from Markit actually increased on a month previous despite the surge in virus cases, rising to a more than five-year high 57.9, albeit this index eased again in December. Consumer spending growth has fallen slightly, although retail sales have remained positive on a year-on-year basis in each of the past six months and were 4.1% higher in November than a year previous, having risen to just shy of an eight-year high in September (Figure 5). We expect the US economy to have outperformed its Euro Area counterpart in the final quarter of 2020. This, we believe, may present a bit of a downside risk to EUR/USD in the short-term.

Figure 5: US Retail Sales & Personal Income (2017 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

The long delay from the US government in providing additional unemployment support is, however, almost certain to have weighed on activity in the final quarter of the year, in our view. The government’s additional $600 a week unemployment insurance benefit scheme, provided as part of the CARES act, expired at the end of July. Talks to extend the scheme beyond this date reached a stalemate, with the Republicans and Democrats unable to reach an accord over the size and details of the measures. A $900 billion COVID-19 relief package was finally signed off in late-December, albeit this will see the aforementioned additional benefits scaled down to $300 a week.

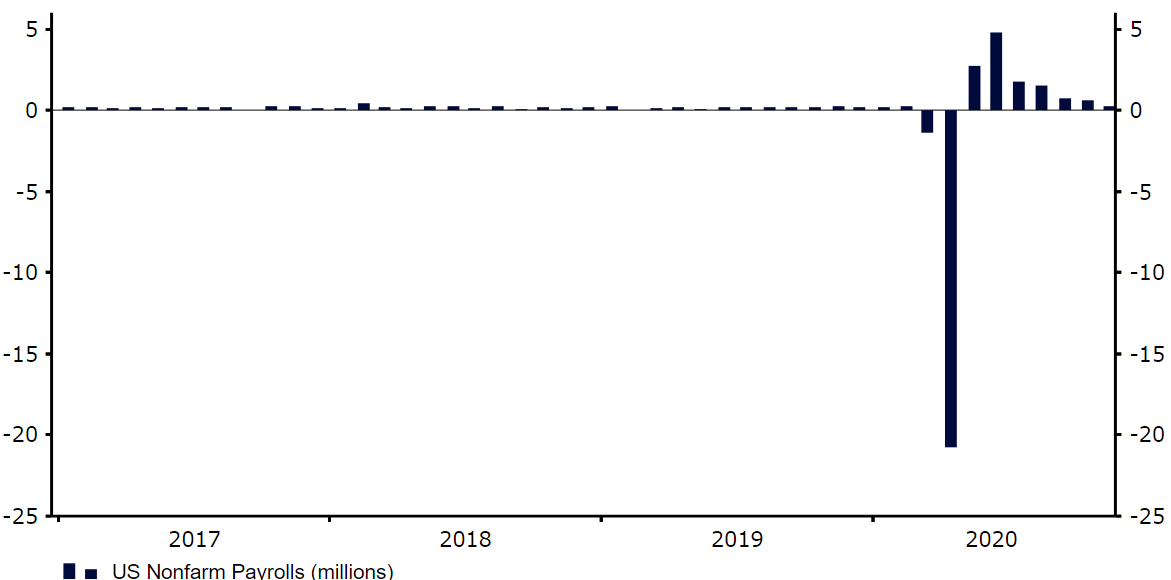

We think that the considerable lag in providing extra stimulus risks a further deterioration in a labour market that has so far only recovered a little of 50% of the total net jobs lost since the start of the crisis (Figure 6). We are already beginning to see signs of a worsening in labour market conditions as containment measures are gradually reintroduced. The moving average of initial jobless claims has increased again, personal income has fallen in five of the past seven months, with the November nonfarm payrolls report also surprising to the downside. The jobless rate has fallen sharply from its peak (14.7% in April to 6.7% in November), although this partly has to do with individuals leaving the labour force.

Figure 6: US Nonfarm Payrolls (2017 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

With most conventional monetary policy tools already in use, we’ve continued to see little policy changes from the Federal Reserve since our last update. The central bank slashed its main fed funds rate by a total of 150 basis points to the effective lower bound (0-0.25%) at the beginning of the pandemic. While the bank has shown no appetite to cut rates into negative territory, it continued to indicate in its December ‘dot plot’ that future hikes remain a long way off and are not likely until at least the end of 2023. Recent communications have also struck a dovish tone, with policymakers warning that adjustments could be made to their quantitative easing programme in an effort to provide additional support to the US economy. The Fed has already pledged to purchase an unlimited amount of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities, although we believe that it is leaving its options open for an increase in the monthly pace of purchases, should it deem necessary. Markets would likely perceive this as a bearish development for the US dollar.

The lack of state coordination and sporadic nature of virus restriction measures reintroduced means that we think that the US economy will likely outperform most of its major peers in Q4, particularly the UK and Euro Area. As mentioned, we think that this presents a bit of a short-term downside risk to EUR/USD, although we remain of the view that the likely path for the dollar this year is lower. While the US is expected to be one of the main beneficiaries of the COVID vaccine from Pfizer and BioNTech, we think that the return to more normal levels of global economic activity in 2021 brought about by the various vaccines should support risk sentiment and weigh on the safe-haven currencies.

As mentioned in our previous G3 revisions, we believe that the weak job retention schemes in the US also ensures that the US labour market is likely to get back on track at a slower rate than most other developed nations once the virus is brought under control. We are therefore continuing to forecast a depreciation of the dollar versus most major currencies in 2021.

Euro (EUR)

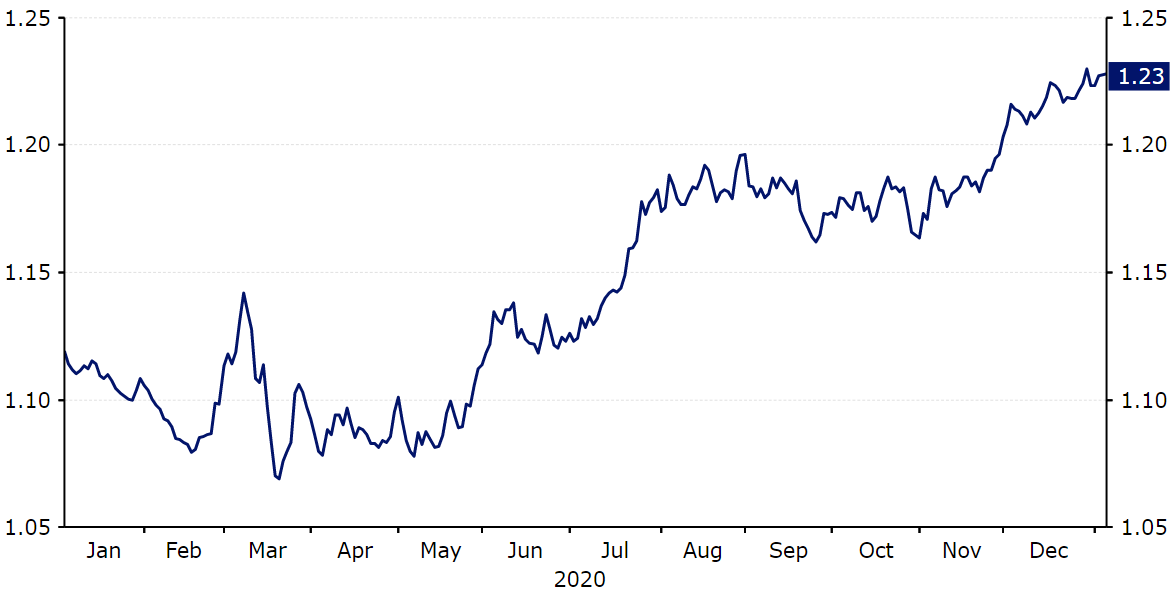

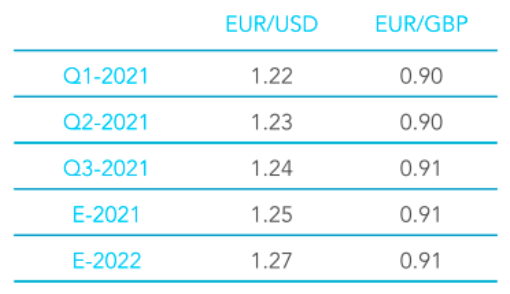

The euro marched higher versus the US dollar in November and December, rallying above the 1.23 level in early-January to its strongest position since March 2018 (Figure 7). The common currency was supported first by the result of the US presidential election and then by the general improvements witnessed in risk sentiment following news of progress towards multiple COVID-19 vaccines.

Figure 7: EUR/USD (January ‘20 – January ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

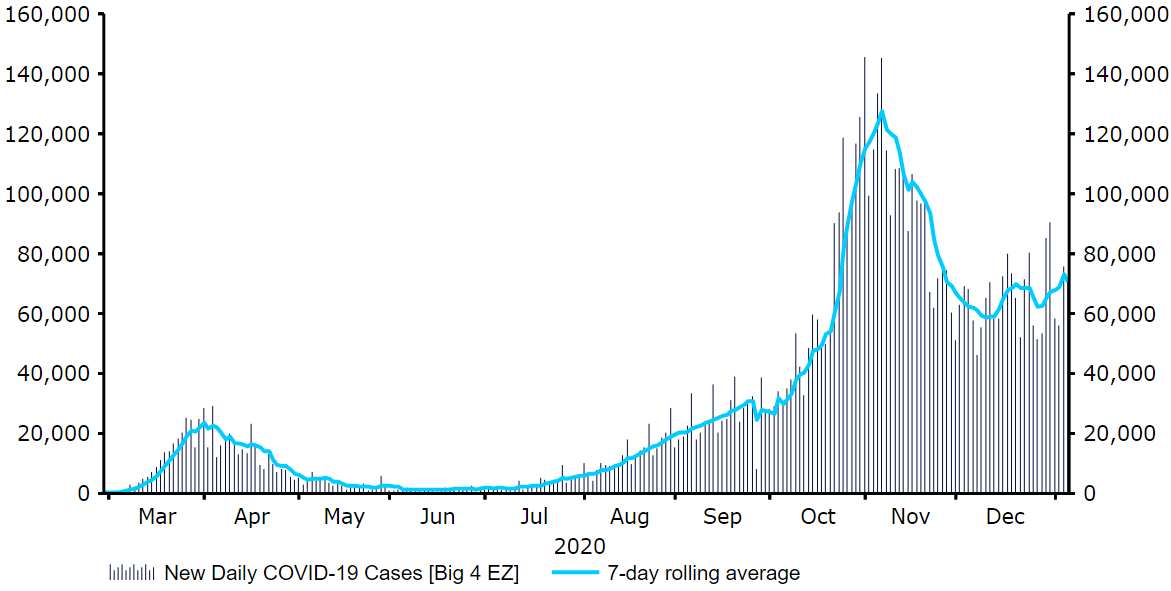

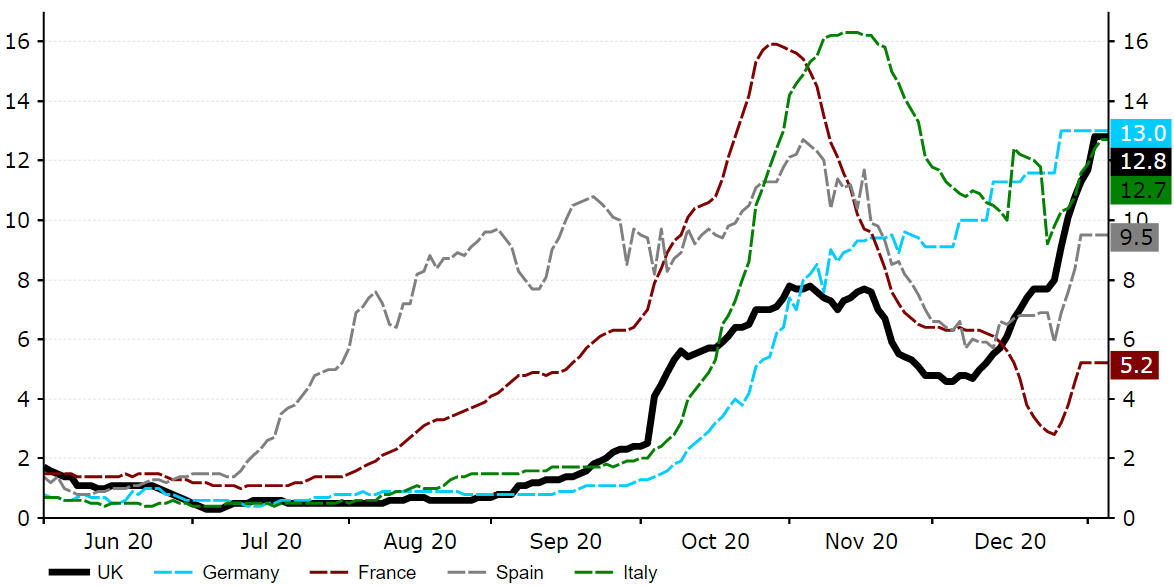

The move higher in the euro comes as the number of new COVID-19 cases during the continent’s second wave of virus infection eases. New daily cases among the four largest countries in the bloc (by population size) began increasing sharply in early-October (Figure 8). Caseloads have retreated since peaking in the first week of November following the re-introduction of containment measures, albeit we note that new tests conducted per capita have levelled off for the most part since then, unlike in the UK where testing has increased sharply. France was the first major country in the bloc to impose another month-long national lockdown at the end of October. Germany followed suit with a more relaxed, partial lockdown on 2nd November, with many other nations in the bloc enforcing a range of measures since then such as tiered systems, nighttime curfews and the early closure of hospitality venues. Test positive rates within the bloc have, for the most part, either stabilised as a result of the measures (such as in Spain and Italy), or eased sharply (e.g Belgium and France).

Figure 8: New COVID-19 Cases [Big 4 EZ] [per 1M people] (March ‘20 – Jan ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

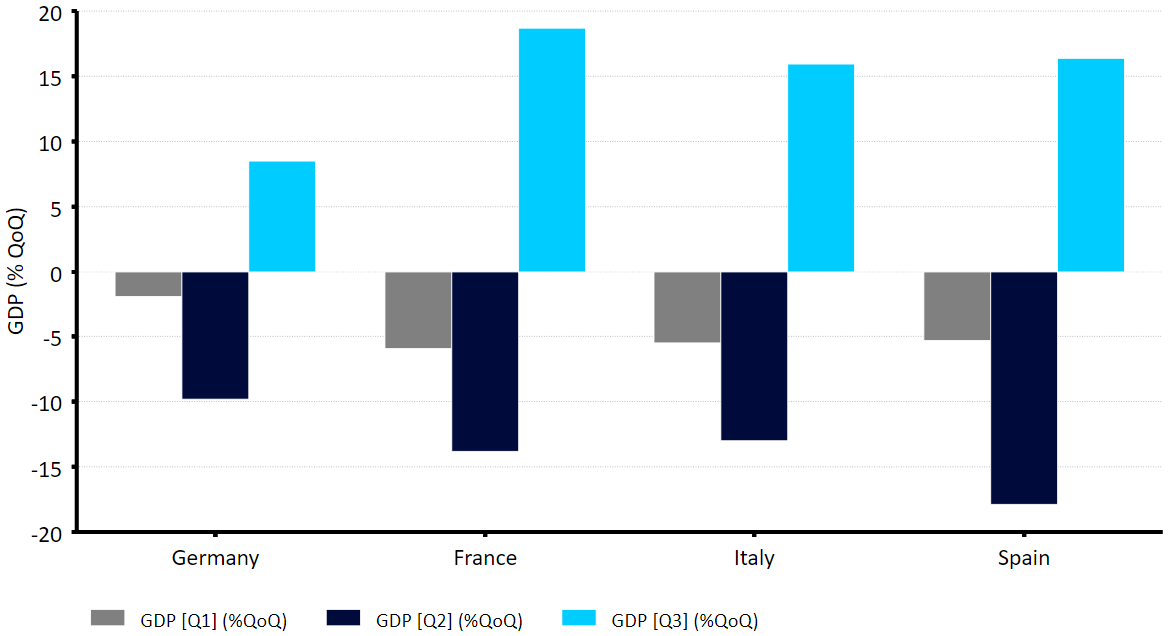

We think that the reintroduction of these stringent virus restriction measures across most of the continent means that another contraction in the Euro Area’s economy in the final quarter of 2020 is inevitable. The bloc’s economy bounced back strongly in the third quarter of year as case numbers dropped dramatically and restrictions were unwound. It grew by 12.5% quarter-on-quarter in the three months to September, with all major nations registering record high levels of expansion. Unsurprisingly, those economies that experienced the harshest lockdown during the early stages of the pandemic contributed the most to this rebound, with France, Italy and Spain all posting growth of between around 16-19% (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Euro Area GDP Growth Rate [by country] (2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

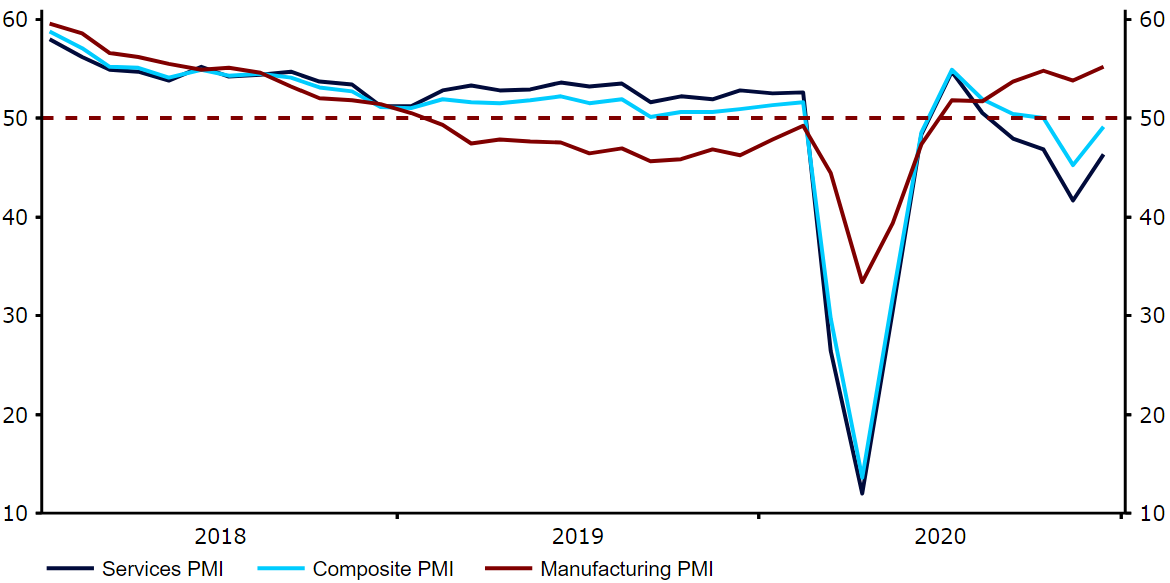

The latest indicators of economic activity have, however, already shown a sharp downtrend, particularly the timely business activity PMIs. The index that denotes activity in the manufacturing sector of the economy has actually proved resilient, despite the strict containment measures, and has remained comfortably in expansionary territory in each of the past six months. By contrast, activity in the services sectors appears to have fallen sharply in Q4, albeit we did witness a rebound in December. The services index sank to a six-month low 41.7 in November, dragging the composite PMI into a deeply contractionary 45.3, its lowest level since May. It is still too early to see the full impact of the recent restrictions on hard indicators of economic activity. We expect growth to turn negative in Q4, although the extent of the downturn will be nowhere near as severe as in Q2, as the latest measures have been softer and imposed over a shorter time period.

Figure 10: Euro Area PMIs (2017 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

As we mentioned in our last update, the European Central Bank has had almost no room to cut interest rates to combat the downside risks posed by the crisis. The Governing Council has instead pledged to inject vast sums of stimulus into the economy via its asset purchase programmes. The bank’s new scheme, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), was expanded and extended again in December, with the ECB committing to purchasing a total envelope of assets worth €1.85 trillion at least through to the end of March 2022. The growth forecast for 2021 was revised lower, with the largest rebound in activity now expected to take place in 2022. Lagarde did, however, appeared slightly more concerned over the strength of the euro. It is our view that the ECB’s aversion to a stronger currency may act to cap gains for the euro in the coming months.

We think that while the prospects for the Euro Area economy in the fourth quarter of 2020 look relatively bleak, activity is likely to bounce back strongly in the first few months of this year. The bloc’s economy will begin receiving injections of stimulus from the EU in 2021, which should help support overall activity. The EU will make available an unprecedented €750 billion fiscal rescue package commencing at the beginning of the year, which will see €360 billion made available in loans and €390 billion in grants. Unlike the US, European governments have also remained committed to supporting jobs during the second wave of the pandemic. Job retention schemes in Germany and France, for instance, have both been extended until the end of 2021. These stimulus measures, combined with the mass roll out of vaccinations should prevent a ‘double-dip’ recession in the Eurozone in the first quarter of the year.

The bloc’s heavy emphasis on supporting businesses to maintain employment during the worst of the crisis will, in our view, allow the Euro Area economy to recover more rapidly than its US counterpart in 2021. This outperformance, combined with an improvement in risk sentiment that we believe the multiple vaccines will bring, means that we continue to envisage gains for EUR/USD over our forecast horizon.

UK Pound (GBP)

Sterling has been one of the better performing currencies in the G10 in the past few months and has raced towards our long-term forecasts faster than we had anticipated.

The pound has rallied by approximately 7% versus the US dollar since late-September, rising to its strongest position since April 2018 at the end of December following news of a post-Brexit trade agreement between the UK and European Union. This rally ensures that the GBP/USD pair is currently trading just below the levels that it was in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote in June 2016. More meaningful gains for the currency have, however, been capped by the latest sharp increase in virus caseloads in Britain and the reimposition of national lockdowns in early-January.

Figure 11: GBP/USD (January ‘20 – January ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

Aside from the pandemic, the main news headlines in the UK in the past few months have continued to be dominated largely by Brexit. In line with our and the markets’ expectations, a modest post-Brexit trade agreement was reached between the UK and the EU on 24th December, which eliminates the possibility of a cliff-edge ‘no-deal’ exit. The deal itself is a thin, bare bones agreement, with much still left to be decided. There will be no tariffs or quotas between the UK and EU, although unilateral tariffs can be imposed in principle. The EU has also imposed significant barriers to food and drink, with additional red tape on manufacturing, chemicals and pharmaceuticals. Significantly, there is no real agreement yet on services, which accounts for around 50% of the UK’s exports to the EU, so there is unlikely to be any massive changes in the near-term. We do, however, think that additional negotiations this year will take place largely in the background and foresee no sizable impact on sterling given the importance the market is placing on the ongoing pandemic.

The encouraging signs of progress towards mass COVID-19 vaccinations also provides reason for optimism. Britain was the first country in the world to begin inoculations using the Pfizer-BioNTech jab on 8th December, with the rollout of the low-cost and easy to store vaccine from Oxford University-AstraZeneca also commencing on 4th January. We think that the UK, and therefore sterling, is set to be among the main beneficiaries of the mass vaccine rollouts in the first half of 2021. Aside from Canada, the UK has so far ordered more vaccine doses per capita than any other country or economic area in the world (approximately six per head).

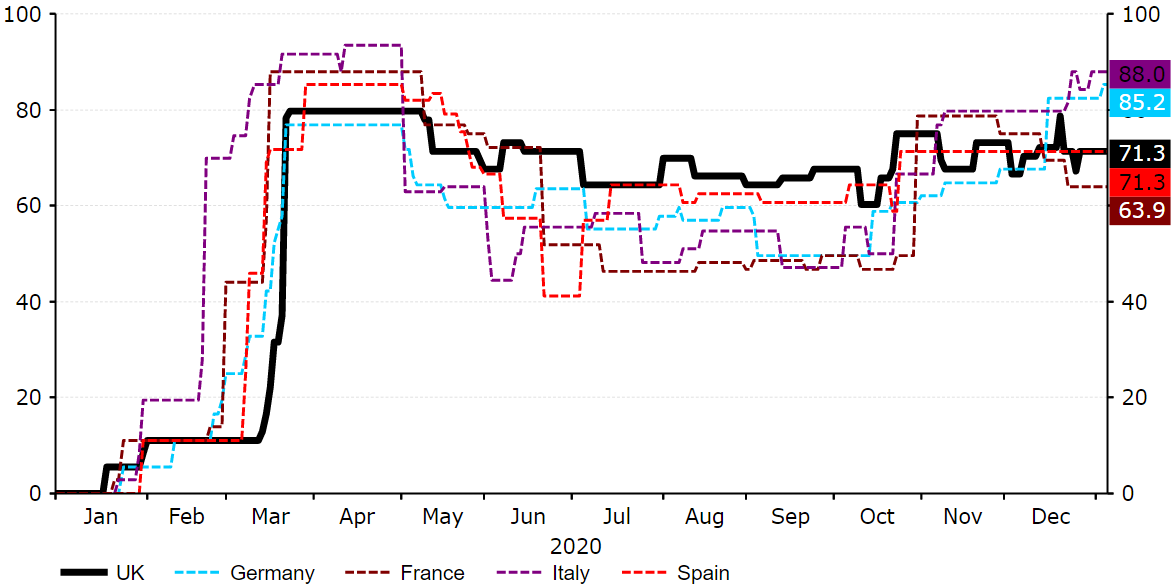

The UK has also been perceived by investors as one of the worst affected countries in Europe by the virus, and therefore may benefit disproportionately once mass vaccinations have taken place. Overall cases as a percentage of the population have actually been relatively mild compared to many of Britain’s major European peers (around 41,500 per 1 million), particularly when taking into account that the UK has conducted more tests per capita than all of the other twenty-four most populous nations in the continent (nearly 850,000 per 1M). Unfortunately, the UK’s COVID death rate per capita is among the highest at more than 1,100 per 1M. As a result, the various restrictions imposed by Boris Johnson’s government since the onset of the crisis have been among the most strict in Europe, evident in the UK’s COVID-19 government response stringency index (Figure 12), courtesy of Oxford University. The average of this index since the beginning of March 2020 is currently higher in the UK than any other nation or economic area in the G10. This suggests to us that the UK economy could receive a relatively larger economic boost once these stringent measures are eventually unwound.

Figure 12: COVID-19 Government Response Stringency Index [UK vs. Big 4 EZ] (2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 05/01/2021

On a more pessimistic note, the recent sharp increase in virus cases in the UK, said to be triggered largely by the emergence of the more aggressive spreading variant of the virus, does present a risk to sterling in the short-term. Virus caseloads have jumped to record highs, with the one-week moving average of deaths also at its highest level since late-April. We note that the UK’s test positive rate (which denotes the percentage of COVID-19 tests that return a positive result) has more than doubled since the beginning of December to around 13% (Figure 13). Investors have also reacted negatively to the reintroduction of national lockdowns in the UK at the beginning of the year, which are set to weigh heavily on economic activity in Q1.

Figure 13: UK vs. Big 4 EZ COVID-19 Test Positive Rate (March ‘20 – January ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 06/01/2021

Activity bounced back strongly in the third quarter of 2020, with the economy expanding by a record 16% quarter-on-quarter. This was driven predominantly by a sharp jump in household consumption (around 18%), supported by the large fiscal response from the UK government. A £330 billion coronavirus stimulus package was unveiled in March (the equivalent of 15% of the UK’s GDP), with a host of other additional measures launched since then aimed at supporting businesses and households. We remain encouraged by the UK government’s heavy focus on job retention, particularly the extension of its furlough scheme through to at least the end of April. Fourth quarter activity is, however, on course to show contraction once again, with the announcement of further strict lockdowns at the beginning of January ensuring that the chances of a double-dip recession are now very much increased.

With the UK economy set for further hardship in early-2021, there is likely to be growing pressure on the Bank of England to ramp up its stimulus measures this year. As anticipated, the bank’s quantitative easing programme was increased for the third time since the onset of the crisis in November, by a larger-than-expected £150 billion to £875 billion. The bank’s communications were also unsurprisingly dovish, with Governor Andrew Bailey hinting at a further increase in the programme down the road if required. GDP forecasts were revised sharply lower, as expected, with a 2% contraction now pencilled in for Q4 versus the 4% expansion that they had previously anticipated.

While the larger-than-expected QE expansion is a sterling negative, investors were encouraged by the bank’s apparent lack of appetite for additional interest rate cuts. There has been very little mention of negative rates in the BoE’s recent communications and the MPC continues to appear torn over the effectiveness of sub-zero rates. Markets have, however, brought forward their expectations for a cut following the latest lockdown announcement and are now pricing in a 10 basis point cut to zero at the August 2021 MPC meeting.

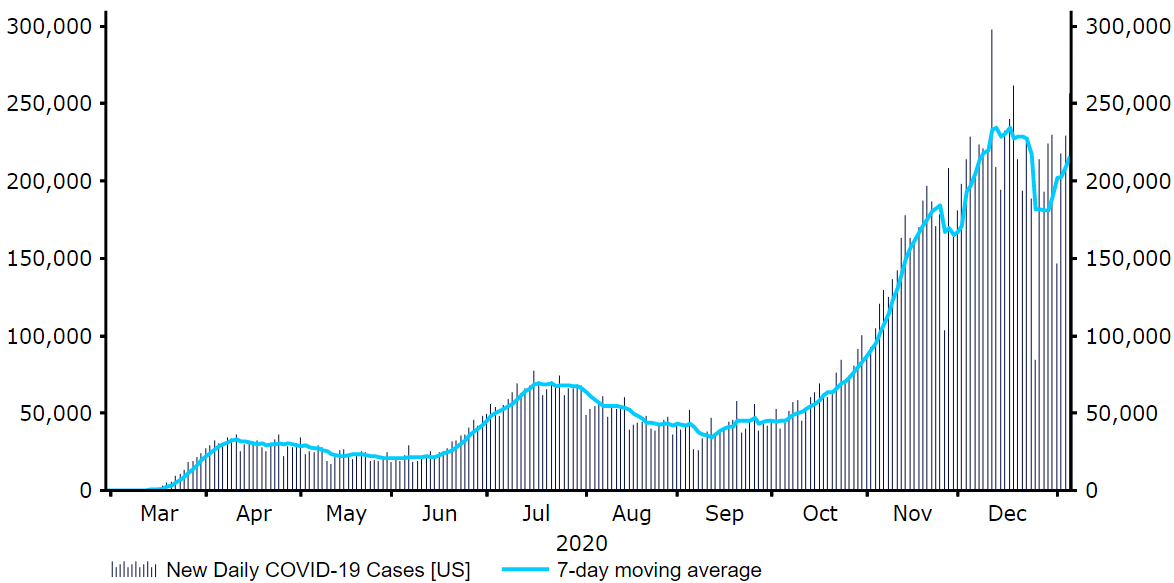

The recent aggressive spread of the COVID-19 virus in Britain, and the reimposition of strict lockdowns at the beginning of the year, undoubtedly presents a short-term downside risk to the pound, in our view. Following the latest encouraging vaccine news we are, however, revising our sterling forecasts for this year modestly higher. As mentioned, we think that the pound will be one of the main beneficiaries in the G10 of the mass rollout of COVID-19 vaccines this year, and think that economic near normality could be restored in the UK towards mid-2021 once the bulk of the restrictions have been unwound. We are, therefore, pencilling in gains for the pound against the US dollar over our forecast horizon, and relative stability versus the euro.