This month’s Bank of England monetary policy meeting is shaping up to be a much more significant one than investors had anticipated.

The soon to be former governor Carney gave the first real hint that lower rates could be on the horizon at the beginning of the year. Speaking during an event on inflation targeting, Carney stated that there would be a ‘relatively prompt response’ from the bank should weakness in the UK economy persist into 2020. Fellow policymaker Silvana Tenreyro struck a similar tone a few days later, claiming that UK growth was likely to undershoot the bank’s November projections and that she would support a rate cut should the economy continue to slow. Gertjan Vlieghe, who joined the rate-setting board in 2015, was even more forthright in his view, saying that he would vote for a rate cut this month, barring an ‘imminent and significant’ turnaround in UK growth data.

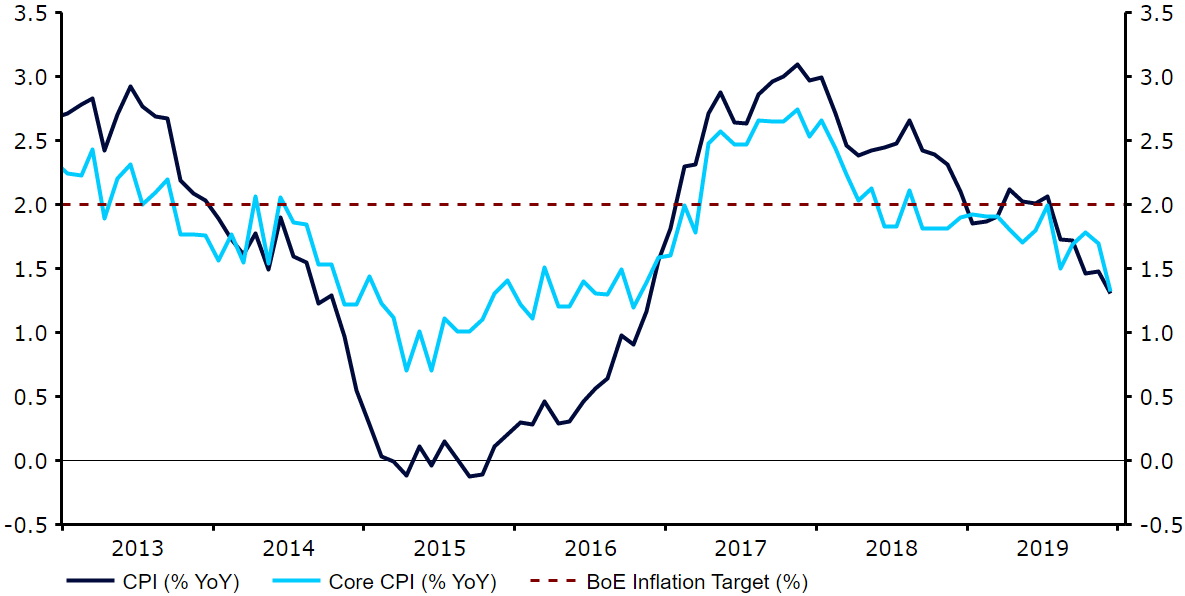

The dovish shift in the committee has come off the back of serially weak UK macroeconomic data since the most recent meeting on 19th December. Of the fifteen data releases that we consider most meaningful since then, nine have surprised to the downside, notably inflation, retail sales and the November growth number. Consumer price growth in the UK is now well short of the BoE’s 2% target. The main headline rate of inflation came in at a three-year low 1.3% year-on-year in December, while the core measure also nosedived to its lowest level since October 2016 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: UK Inflation Rate (2013 – 2019)

Retail sales massively undershot expectations last month with 2020, on the whole, the worst year for consumer spending in the UK in twenty-five years according to the British Retail Consortium (BRC). Of even greater cause for concern for policymakers will be the rotten November GDP growth number, which showed that the UK economy contracted by 0.3% month-on-month. While undoubtedly disappointing, it is worth noting that activity in November was very likely to have been dragged lower by the intense political uncertainty surrounding the general election and Brexit – uncertainty that has, of course, since receded.

Figure 2: UK Macroeconomic Data (since December BoE meeting)

, That being said, we did receive a much better-than-expected set of business activity PMI data out on Friday that has somewhat cooled expectations for a rate cut. The crucial services index, which accounts for around 80% of overall UK GDP, leapt to a sixteen-month high 52.9 in January, a sharp rebound from the December number. While the manufacturing index remained below the level of 50 that denotes contraction, even this moved sharply higher from December’s lows.

The strength of the data is not particularly surprising, given that it covered the first full month since Boris Johnson’s emphatic election victory on 12th December, which effectively removed the entirety of the short-term ‘no deal’ Brexit uncertainty. We had said prior to the data that we thought the key to whether or not the Bank of England cuts interest rates next week could depend on the strength of the January PMI figures. Now that the data has been released, we think that the MPC will have enough justification to refrain from cutting rates on Thursday, although it is likely to be a close call.

At the December meeting, members Saunders and Haskel both dissented in support of an immediate cut, with the vote split 7-2 in favour of no change. Even following Friday’s strong PMI numbers, we think that there is a decent chance that Vlieghe and Tenreyro follow suit. On the other end of the spectrum, hawks Ramsden and Haldane are very unlikely to vote for a cut this time around, particularly given their recent arguments regarding the need for a more restrictive policy. Jon Cunliffe has recently warned that prolonged easing may risk financial instability. Ben Broadbent has also appeared to place a greater onus on UK labour data, which has actually remained pretty resilient of late. Governor Mark Carney himself appears to be the most on the fence, although we think he’s now more likely than not to side with the hawks at the January meeting.

Figure 3: Bank of England Hawk-Dove Scale

, In the event of a cut, which we believe would be a ‘one and done’, we actually think that the reaction in the FX market could be relatively mild. This cut, we believe, would be of a similar ‘insurance’ nature to that conducted by the Federal Reserve in the US and certainly not part of a sustained easing cycle. Currency traders also appear to be taking the prospect of lower rates in their stride, with optimism surrounding Brexit offsetting much of the rate cut concerns. During the time in which market pricing for a January cut has risen from effectively zero to more than 50% (07/01-23/01), the GBP/USD cross has actually emerged more-or-less unchanged. So while we would expect a sell-off in the pound in the event of a cut, the magnitude of the move is, in our view, likely to be contained.

Should policymakers again vote in favour of stable rates, our base case scenario, we think a move higher in sterling would ensue given the relatively high market pricing for a cut. With UK economic data expected to improve in the coming months, January may prove to be the last opportunity the bank has to deliver its ‘insurance cut’ before domestic macroeconomic fundamentals simply do not warrant lower rates.