Central banks return to the centre of attention

( 6 min )

- Go back to blog home

- Latest

In light of its significant impact on public health and the global economy, the COVID-19 pandemic has been the number one topic of interest for financial markets since early-2020.

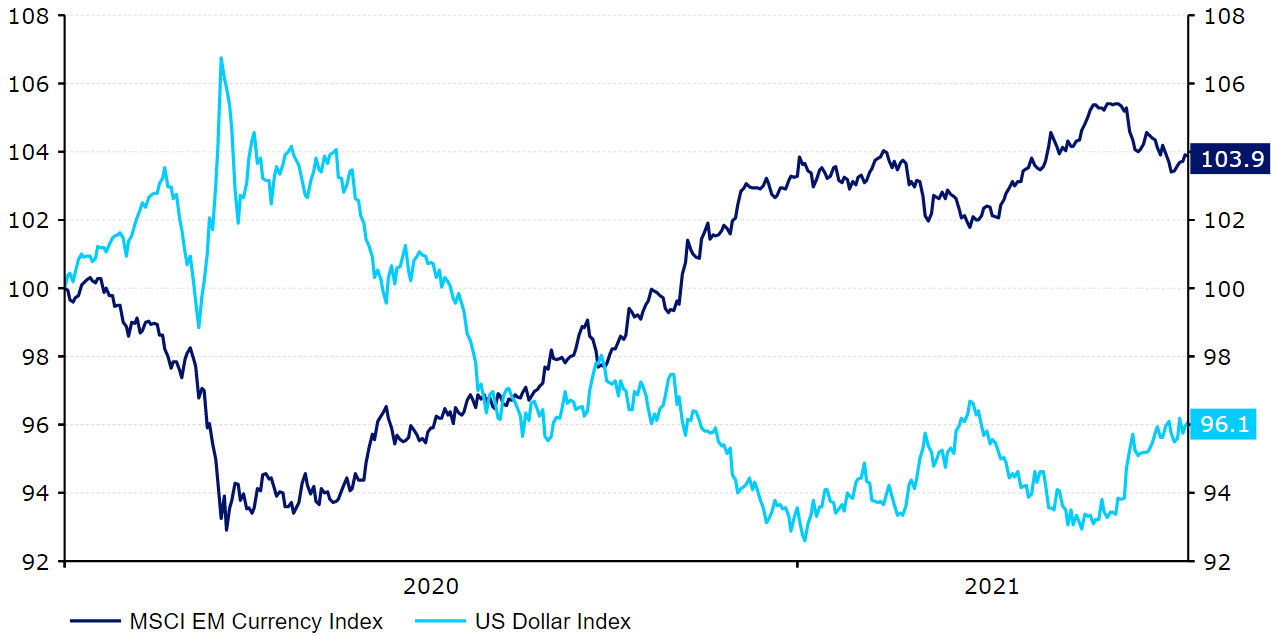

Figure 1: US Dollar Index vs. MSCI EM Currency Index [base = 100] (2020 – 2021)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 27/07/2021

The battle against the virus still has some way to go, but vaccinations have accelerated. In countries with high vaccination rates, the risk of significant curbs being reimposed has diminished, despite the fast spread of new variants. One of the main examples is the UK, where nearly 70% of the population have received at least one vaccine dose. While caseloads have rocketed back up to more than 40,000 per day this month, the number of new hospitalisations and deaths caused by the virus in this wave has, so far, been significantly lower than at the same stage in previous waves (Figure 2). The UK can be viewed as somewhat of a proxy for other developed nations with similar vaccination rates, particularly the US and most of the EU.

Figure 2: UK New COVID-19 Cases & Deaths [2nd Wave vs. 3rd Wave]

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 27/07/2021

Countries with low vaccination rates, particularly emerging market ones, remain vulnerable. In many of them the new variants have resulted in a significant increase in contagion levels. India has been a prime example of this, although we’ve also seen a surge in infection in other countries in Southeast Asia as a result of the delta variant. Now that most of the populations have been vaccinated in the key economic areas, risks related to the spread of these variants have largely eased. For the most part, we are seeing idiosyncratic moves in exchange rates of those countries that are posting sharp increases in cases coupled with significant jumps in hospitalisations and deaths.

With vaccination programmes now in full swing, and inflationary pressures rising around the world, market attention has shifted towards the more conventional topic of monetary policy. Following the sharp increase in global inflation, we have witnessed a number of central banks becoming less dovish since the beginning of the year. A handful of emerging market ones have already begun the process of raising interest rates. In March, central banks in both Brazil and Russia commenced hiking cycles. Since then, both central banks have raised rates by a total of 225 basis points, while keeping the door open to further tightening.

We saw similar developments in Central and Eastern Europe in June, with central banks in both Hungary and Czech Republic hiking rates and suggesting they might continue doing so at upcoming meetings. In the case of Hungary, it was the first such move in a decade and was followed by a larger-than-expected hike in July. Mexico also tightened policy in the summer, with Banxico unexpectedly hiking its base rate by 25 basis points to 4.25% in June, although it’s unclear whether this marks the start of a tightening cycle.

The main developed economies have seen so far few actual steps towards monetary or fiscal tightening, but are seeing a tentative shift in tone nonetheless as inflationary pressures increase globally (Figure 3). A sharp increase in commodity prices, faster than expected rebounds in economic activity and a tightening in labour market conditions have forced major central banks to revise upwards their inflation projections. A number of policymakers expect the period of ultra-loose monetary policy to end sooner than previously thought.

Figure 3: G10 3-month Annualised Core Inflation Rate (latest available)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 27/07/2021

Looking at G10 countries, the Bank of Canada has already begun tapering its QE programme, reducing the pace of weekly purchases from CAD$4 billion to CAD$2 billion. The Bank of England slowed the pace of its weekly purchases from £4.4 billion from £3.4 billion in May, albeit emphasised that the action ‘should not be interpreted as a change in the stance of monetary policy’. Nonetheless, with the bank expecting inflation to reach 3% or more in late-2021, the need for tapering appears to have been brought forward. At its July meeting, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand also surprised investors by announcing it will end its NZ$100 billion QE programme effective on 23rd July.

Among the G10 nations, a handful have already started talking about increasing interest rates or are, at least, flirting with the idea. We think that Norway is likely to be the first to raise rates. Norway is, however, somewhat of an outlier given that it has among the most negative real rates in the G10 and hasn’t launched a QE programme during the pandemic period. The bank’s June communication suggests that a hike may be just around the corner. Øystein Olsen, Norges Bank Governor, stated after the meeting that ‘the policy rate will most likely be raised in September’. New Zealand’s QE announcement has also raised expectations of higher rates, possibly as soon as the bank’s August meeting. We think we’ll see at least these two announce their first hikes before the end of 2021, with more G10 central banks set to commence their hiking cycle in 2022. The currencies of those G10 countries on course to raise rates before the end of 2022 look well placed to outperform and are, indeed, among those that we expect to perform the best over our forecast horizon.

Figure 4: Expected Timing of G10 Interest Rate Hikes [based on market pricing*]

Source: Ebury/Bloomberg Date: 27/07/2021

*assumes 15 basis point hike for BoE and RBA, 25 basis points for rest

The most important monetary policy maker worldwide remains the Federal Reserve, sometimes described as ‘the world’s central bank’. The Fed’s policy stance is particularly important for those emerging market countries that are heavily dependent on external financing in US dollars. The FOMC’s June meeting delivered an unexpected hawkish shift, with most policymakers now pencilling in at least two interest rate hikes before the end of 2023. The market reacted by pushing the US dollar higher, at the expense of EM currencies. Fed policy tightening could pressure these currencies lower. The latest ‘dot plot’ suggests that higher interest rates may not be on the cards for at least another year-and-a-half or so (Figure 5), although we wouldn’t be surprised to see another upward shift in these projections in September.

Figure 5: FOMC ‘Dot Plot’ [June 2021]

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 27/07/2021

We think that a tightening of monetary policy in the US could work in favour of the dollar, particularly against currencies of those countries whose central banks fail to follow suit. That being said, we think that many EM currencies should be able to withstand the depreciating pressure by engaging in their own tightening cycles. Indeed, the market is currently either pricing in a continuation or the start of a tightening cycle in most EM countries over the coming twelve months, particularly in Latin America and Europe. This supports our bullish view of these currencies over the medium-term. Moreover, the political pressure against policy tightening in the US suggests the gap between FOMC rhetoric and actual interest rate moves may be quite large. This would ensure that the rate gap with the US may grow in favour of EM currencies for some time yet.

We have listed below upcoming central bank monetary policy meeting dates for the G10 and key emerging market countries between now and the end of the year. Volatility in the FX market is likely to be heightened around the time of these decisions.

| Date | Location | Monetary Policy Announcement |

| July | ||

| 6th July | Australia | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| 7th July | Romania | National Bank of Romania |

| 8th July | Malaysia | Central Bank of Malaysia |

| 8th July | Poland | National Bank of Poland |

| 9th July | Peru | Central Reserve Bank of Peru |

| 14th July | Canada | Bank of Canada |

| 14th July | Chile | Central Bank of Chile |

| 14th July | New Zealand | Reserve Bank of New Zealand |

| 15th July | Korea | Bank of Korea |

| 16th July | Japan | Bank of Japan |

| 20th July | China | People’s Bank of China |

| 22nd July | Eurozone | European Central Bank |

| 22nd July | Indonesia | Bank Indonesia |

| 22nd July | South Africa | South African Reserve Bank |

| 23rd July | Russia | Central Bank of Russia |

| 27th July | Hungary | Central Bank of Hungary |

| 28th July | US | Federal Reserve |

| 30th July | Colombia | Central Bank of Colombia |

| August | ||

| 3rd August | Australia | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| 4th August | Brazil | Central Bank of Brazil |

| 4th August | Thailand | Bank of Thailand |

| 5th August | Czechia | Czech National Bank |

| 5th August | UK | Bank of England |

| 6th August | India | Reserve Bank of India |

| 6th August | Romania | National Bank of Romania |

| 12th August | Mexico | Bank of Mexico |

| 13th August | Peru | Central Reserve Bank of Peru |

| 18th August | New Zealand | Reserve Bank of New Zealand |

| 19th August | Indonesia | Bank Indonesia |

| 19th August | Norway | Norges Bank |

| 20th August | China | People’s Bank of China |

| 24th August | Hungary | Central Bank of Hungary |

| 26th August | Korea | Bank of Korea |

| 26-28th August | Jackson Hole Symposium | |

| 31st August | Chile | Central Bank of Chile |

| September | ||

| 7th September | Australia | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| 8th September | Canada | Bank of Canada |

| 8th September | Poland | National Bank of Poland |

| 9th September | Eurozone | European Central Bank |

| 9th September | Malaysia | Central Bank of Malaysia |

| 10th September | Peru | Central Reserve Bank of Peru |

| 10th September | Russia | Central Bank of Russia |

| 20th September | China | People’s Bank of China |

| 21th September | Sweden | Sveriges Riksbank |

| 21st September | Hungary | Central Bank of Hungary |

| 21st September | Indonesia | Bank Indonesia |

| 22nd September | Brazil | Central Bank of Brazil |

| 22nd September | Japan | Bank of Japan |

| 22nd September | US | Federal Reserve |

| 23rd September | UK | Bank of England |

| 23rd September | Norway | Norges Bank |

| 23rd September | South Africa | South African Reserve Bank |

| 23rd September | Switzerland | Swiss National Bank |

| 29th September | Thailand | Bank of Thailand |

| 30th September | Colombia | Central Bank of Colombia |

| 30th September | Czechia | Czech National Bank |

| 30th September | Mexico | Bank of Mexico |

| October | ||

| 5th October | Australia | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| 5th October | Romania | National Bank of Romania |

| 6th October | New Zealand | Reserve Bank of New Zealand |

| 6th October | Poland | National Bank of Poland |

| 8th October | Peru | Central Reserve Bank of Peru |

| 8th October | India | Reserve Bank of India |

| 12th October | Korea | Bank of Korea |

| 13th October | Chile | Central Bank of Chile |

| 19th October | Hungary | Central Bank of Hungary |

| 20th October | China | People’s Bank of China |

| 21st October | Indonesia | Bank Indonesia |

| 22nd October | Russia | Central Bank of Russia |

| 27th October | Brazil | Central Bank of Brazil |

| 27th October | Canada | Bank of Canada |

| 28th October | Eurozone | European Central Bank |

| 28th October | Japan | Bank of Japan |

| 29th October | Colombia | Central Bank of Colombia |

| NLT* 14th October | Singapore | Monetary Authority of Singapore |

| November | ||

| 2nd November | Australia | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| 3rd November | Malaysia | Central Bank of Malaysia |

| 3rd November | Poland | National Bank of Poland |

| 3rd November | US | Federal Reserve |

| 4th November | Czechia | Czech National Bank |

| 4th November | UK | Bank of England |

| 4th November | Norway | Norges Bank |

| 9th November | Romania | National Bank of Romania |

| 10th November | Thailand | Bank of Thailand |

| 11th November | Mexico | Bank of Mexico |

| 11th November | Peru | Central Reserve Bank of Peru |

| 16th November | Hungary | Central Bank of Hungary |

| 18th November | Indonesia | Bank Indonesia |

| 18th November | South Africa | South African Reserve Bank |

| 22nd November | China | People’s Bank of China |

| 24th November | New Zealand | Reserve Bank of New Zealand |

| 25th November | Sweden | Sveriges Riksbank |

| 25th November | Korea | Bank of Korea |

| December | ||

| 7th December | Australia | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| 8th December | Brazil | Central Bank of Brazil |

| 8th December | Canada | Bank of Canada |

| 8th December | Poland | National Bank of Poland |

| 8th December | India | Reserve Bank of India |

| 9th December | Peru | Central Reserve Bank of Peru |

| 14th December | Chile | Central Bank of Chile |

| 14th December | Hungary | Bank of Hungary |

| 15th December | US | Federal Reserve |

| 16th December | Eurozone | European Central Bank |

| 16th December | UK | Bank of England |

| 16th December | Indonesia | Bank Indonesia |

| 16th December | Mexico | Bank of Mexico |

| 16th December | Norway | Norges Bank |

| 16th December | Switzerland | Swiss National Bank |

| 17th December | Colombia | Central Bank of Colombia |

| 17th December | Japan | Bank of Japan |

| 17th December | Russia | Central Bank of Russia |

| 20th December | China | People’s Bank of China |

| 22nd December | Czechia | Czech National Bank |

| 22nd December | Thailand | Bank of Thailand |

*NLT=no later than

Sources: Central bank websites, Bloomberg

You can now listen to the latest episode of our FX Talk Podcast: