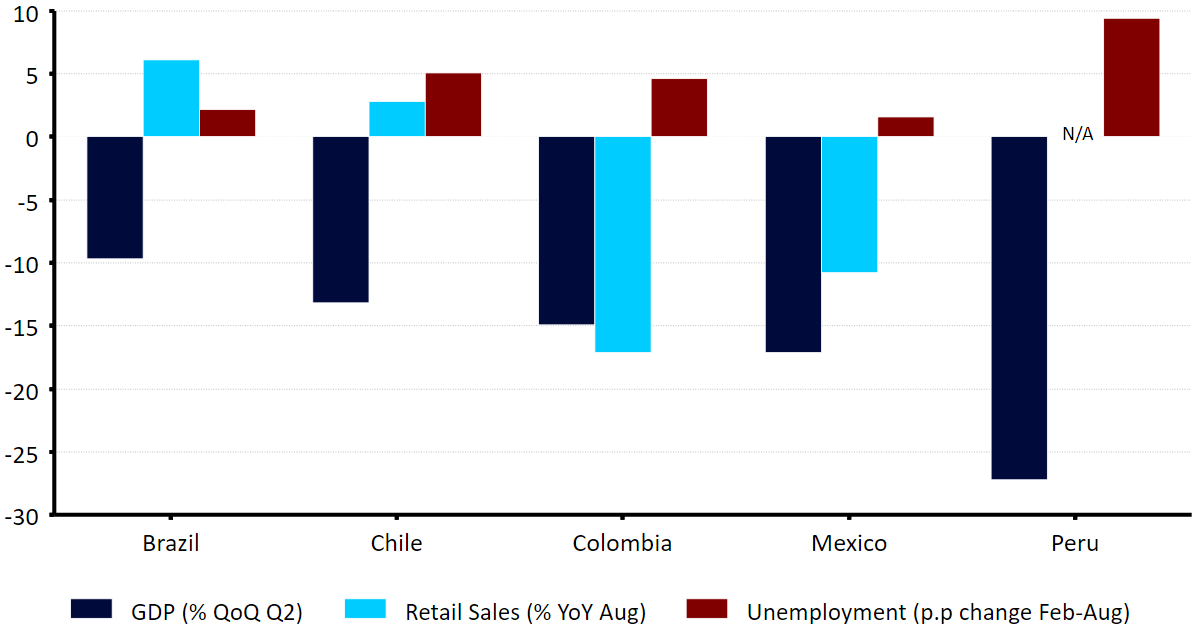

Latin America FX Forecast Revision

( 10 )

- Go back to blog home

- Latest

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit the Latin American region particularly hard since the onset of the crisis.

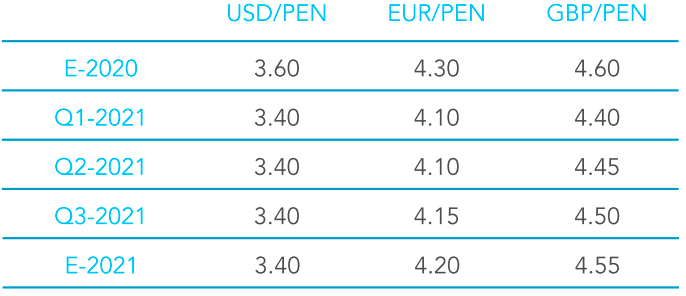

Figure 1: COVID-19 Confirmed Cases [per 1M people] [Latin America] (as of 06/11)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 03/11/2020

COVID-19 deaths as a percentage of the population, which tends to provide a more accurate representation of the severity of the virus’ spread in counties with inadequate levels of testing, also has Peru as the worst affected country in the region. Barring the microstate of San Marino and Belgium, Peru currently has the highest number of COVID-19 deaths per capita in the world (1,044 per 1 million people) according to worldometers. Brazil (752), Chile (746) and Mexico (712) are not too far behind, with Colombia having the fewest fatalities per capita of the five thus far (620).

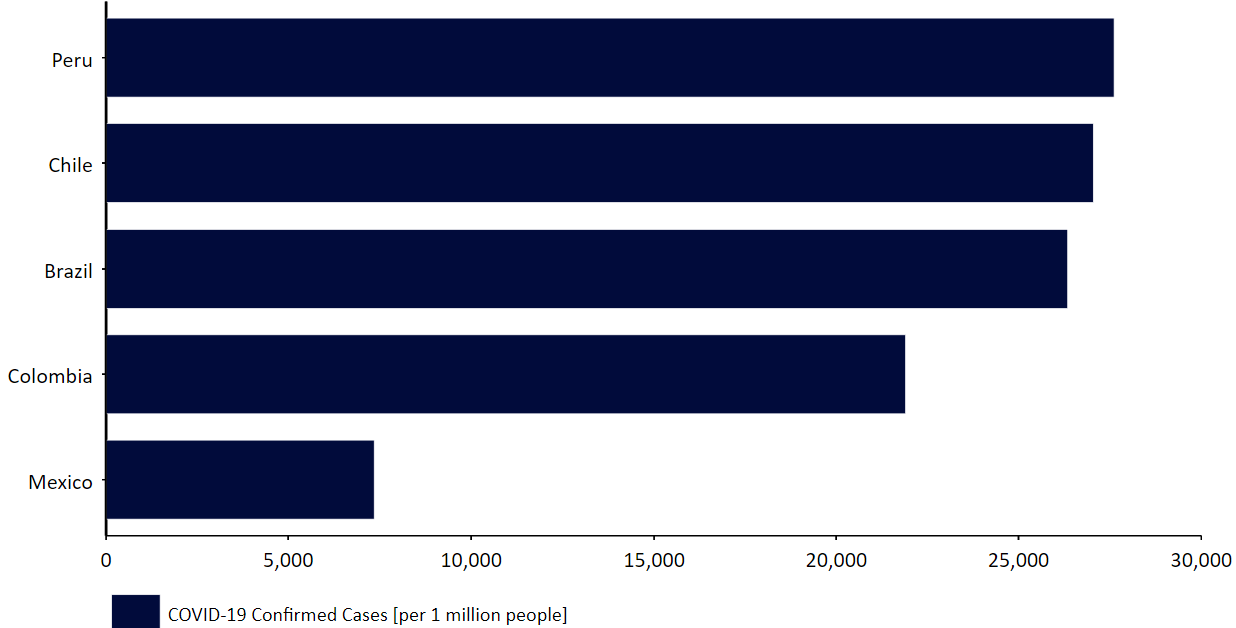

Figure 2: LatAm COVID-19 Deaths [per 1M] [4-week moving average] (Mar ‘20 – Oct ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 28/10/2020

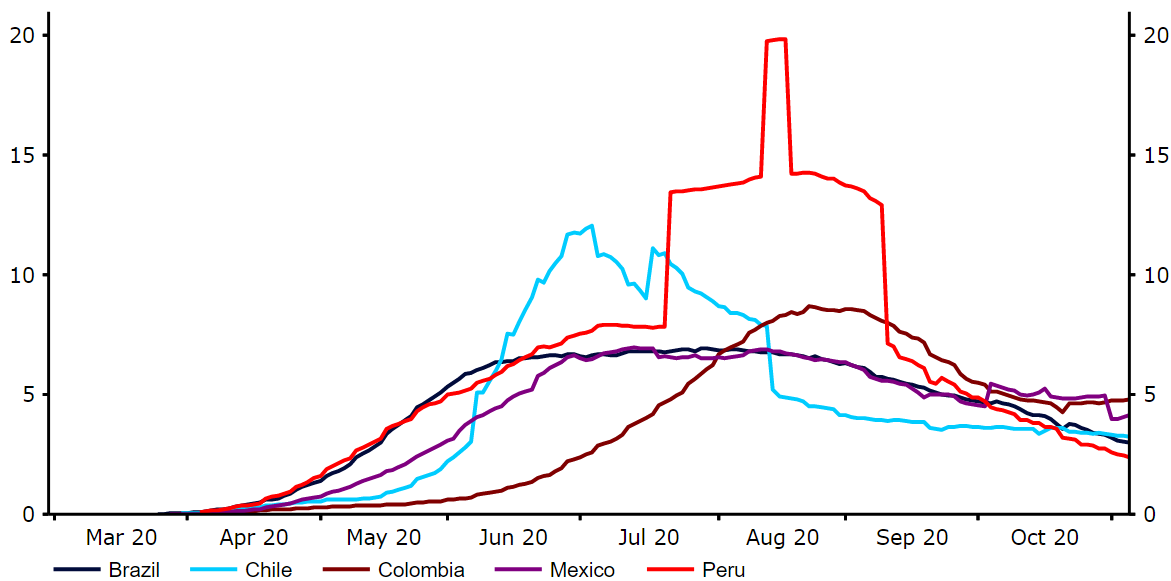

As has been the case across the globe, the various national and regional measures put in place to limit the spread of the virus have weighed significantly on economic output in Latin America. As a consequence of its much stricter lockdown measures, Peru’s economy suffered from the largest contraction of all the Latin American countries we cover in the second quarter of the year (-27.2% QoQ), with Brazil (-9.7%) experiencing the smallest. Since then, we have witnessed a generalised rebound in economic output in the region as restrictions have been gradually unwound. Consumer spending, as represented by retail sales, has bounced back sharply in some instances (notably in Brazil and Chile), where large levels of fiscal support have been made available by the local government, and remained subdued in others (such as Colombia and Mexico). Unemployment has eased since the peak of the crisis, although remains high in the region and above pre-pandemic levels in all five countries, considerably so in Peru (+9.4 p.p).

Figure 3: LatAm Macroeconomic Performance [during COVID-19 pandemic]

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 28/10/2020

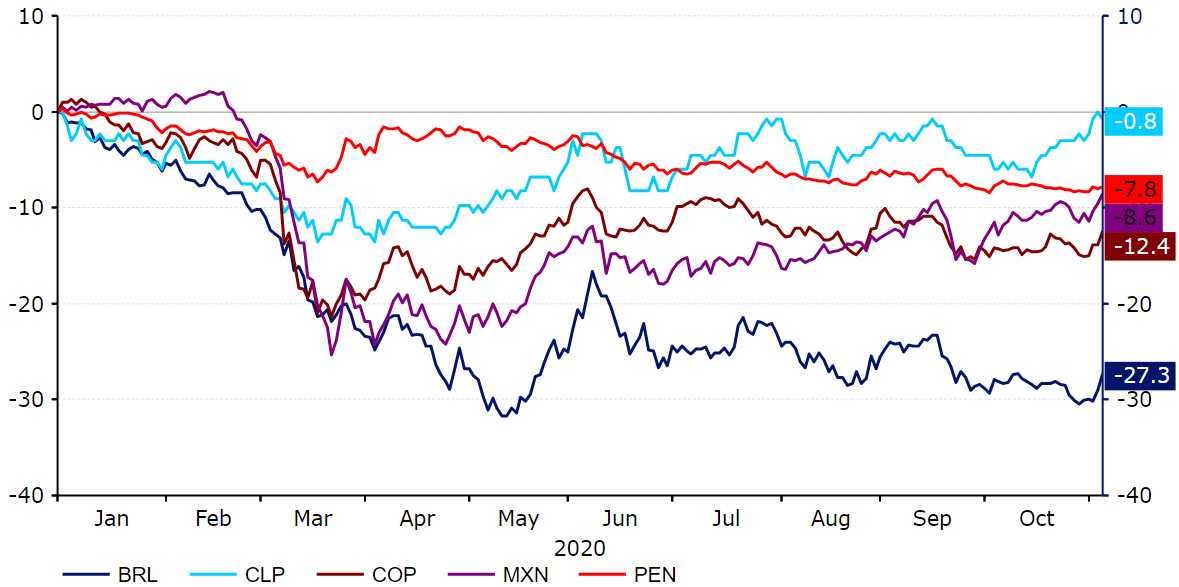

The outbreak of the pandemic triggered an aggressive risk-off mode in financial markets during the first quarter of 2020. While most emerging market currencies have rebounded from their lows, the majority continue to trade lower versus the US dollar year-to-date, including all five of the Latin American currencies in this report. The Chilean peso (CLP) has proved the most resilient, currently trading almost flat versus the USD YTD (Figure 4). By contrast, the Brazilian real has sold-off aggressively in the past few months and has been one of the worst performing currencies in the world this year.

Figure 4: Latin America FX Performance vs. USD [% change] (YTD)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 28/10/2020

We believe that these sell-offs have left all five currencies at levels that are not necessarily justified by economic fundamentals. We are therefore forecasting rebounds in all of them versus the US dollar between now and the end of 2021, particularly given our view for a recovery in risk appetite once the global pandemic situation is brought under control. We are pencilling in the bulk of these projected gains to occur between now and the end of Q1 2021, when news on the rolling out of a vaccine will hopefully be available. A resurgence in the virus in the region in the coming months does, however, provide a risk to this view.

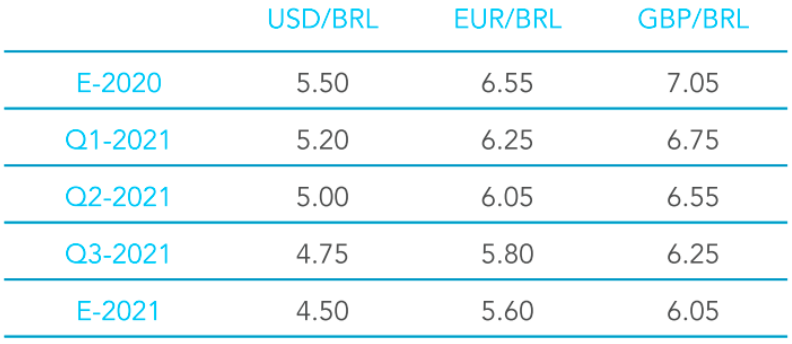

Brazilian Real (BRL)

The Brazilian real (BRL) has been one of the worst performing currencies in the world since the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus turned it into a full-blown pandemic.

The currency lost almost one-third of its value versus the US dollar at one stage, as investors flocked to low beta assets and sold those deemed as higher risk during the first half of 2020. This sell-off sent the currency to its lowest ever level at just shy of 6 to the USD in May. The currency rebounded sharply through to early-June, although sold-off again in the four months through to late-October. It has, however, recovered sharply again following the US election.

Generalised criticism of Brazilian authorities’ handling of the pandemic was behind much of the real’s dramatic collapse in the second quarter of the year. Far-right President Jair Bolsonaro has adopted a troublesome approach to dealing with the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus, actively encouraging people to defy social distancing, ignore regional lockdown and partake in large gatherings. He has also given the green light for the mass distribution of the pill chloroquine, despite the lack of scientific evidence that it helps treat the virus.

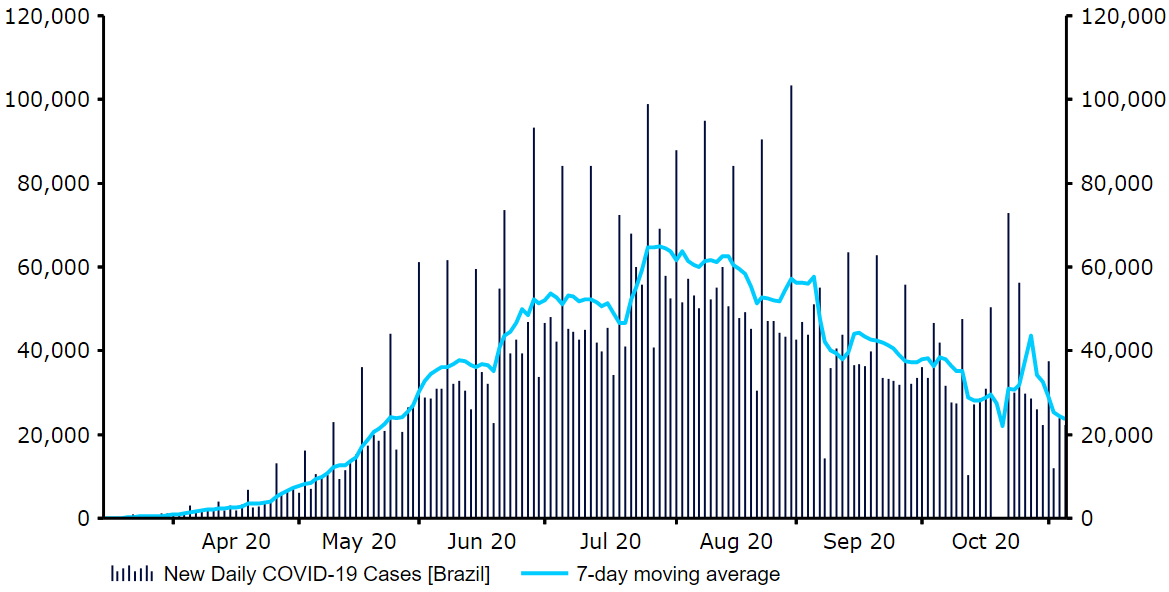

Brazil has now racked up the third largest number of reported cases of the virus in the world, in excess of 5.5 million, and over 160,000 deaths at the time of writing. These numbers are likely much higher in reality due to relatively limited levels of testing – 103 tests conducted per 1,000 people versus 450 per 1,000 in the US. New daily cases of the virus have, however, begun to ease gradually in Brazil in the past few weeks, albeit very gradually. The one week moving average of deaths caused by the virus has also slowed, although again only very gradually and at a rate much slower than witnessed among developed nations.

Reports that the majority of the population in some of Brazil’s largest cities ignored isolation orders is likely to have helped spread the virus at a faster rate that we have witnessed across much of the rest of the world. This inability to rein in the number of new infections risks anchoring Brazil in a prolonged recessionary period. The Brazilian entered back into recession in Q2, posting a record 9.7% quarter-on-quarter contraction. Activity data since then has been largely encouraging, notably the jump in retail sales back into positive annual territory in each of the three months through to August. Sales grew by a record 6.1% year-on-year in August, largely due to an easing in virus restrictions and fiscal stimulus targeted at low-income families. Momentum in consumer spending activity does, however, appear to be easing and is expected to slow further should fiscal support be unwound before the end of the year, as is expected.

Figure 2: New Daily COVID-19 Cases [Brazil] (March ‘20 – November ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 03/11/2020

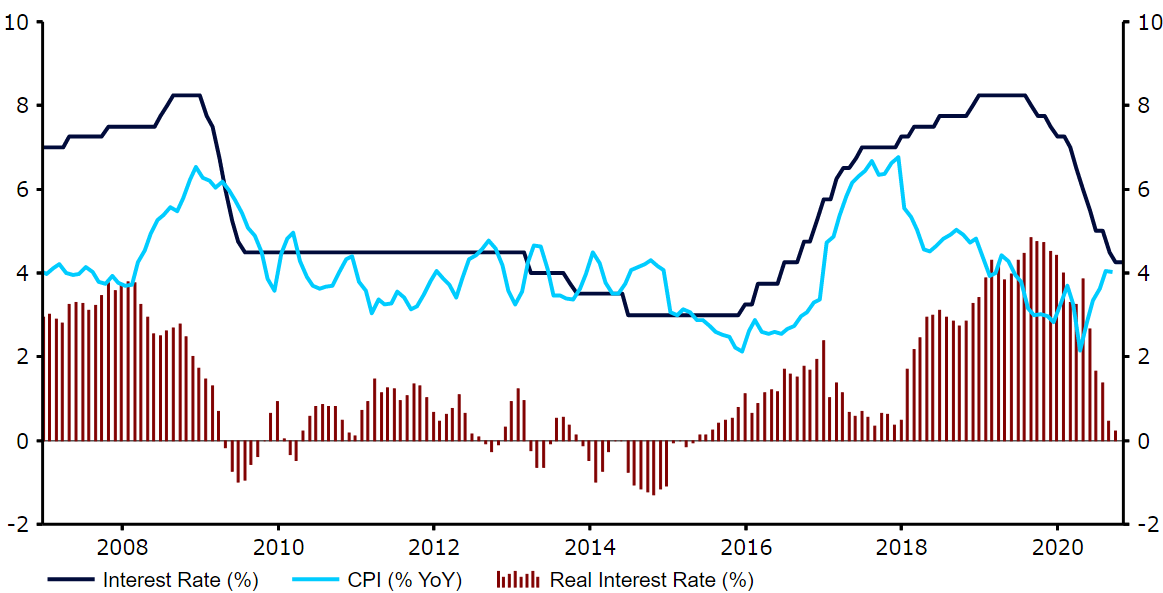

Even prior to the COVID outbreak, investors had placed a large risk premium on Brazil in light of the country’s heightened political uncertainty. Like many of his predecessors, President Bolsonaro faced allegations of corruption that have resulted in calls for his impeachment, albeit this now seems a remote possibility. Until recently, investors were compensated for Brazil’s heightened political risk premium by the country’s very high real interest rates, which peaked at almost 8% in 2017. A series of interest rate cuts from the Central Bank of Brazil so far this year in response to the crisis has, however, significantly lowered the currency’s appeal. Rates have been slashed by a total of 225 basis points since the onset of the pandemic, with the central bank cutting by another 25 basis points during its September meeting to a record low 2%. This has significantly dented Brazil’s appeal from a carry trade perspective, particularly now that real interest rates have fallen into negative territory for the first time since December 1997.

There is some good news, however, in Brazil’s solid macroeconomic fundamentals. Purely from that perspective, we think that BRL is one of the better placed EM currencies to weather additional losses during the pandemic.

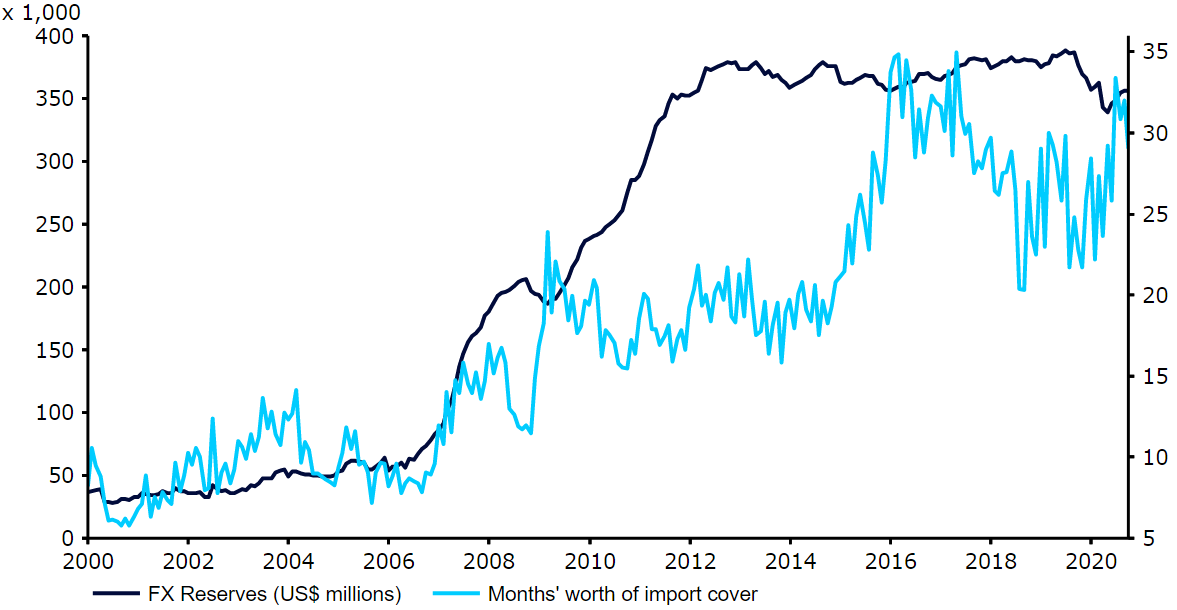

High FX reserves that equate to around 30 months’ worth of import cover. This is an ample level of ammunition for the Central Bank of Brazil to successfully intervene in the market in order to reverse the currency’s sell-off. Central bank President Roberto Campos Neto has stated that the bank has plenty of room to intervene and may step up its efforts to support the currency, should it deem necessary. He did, however, note in September that the bank ‘lacked the proper tools to combat high volatility’, stating that it was more straightforward to merely tackle currency weakness.

Figure 3: Brazil FX Reserves (2000 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 22/09/2020

Low levels of external debt that equate to approximately 18% of GDP – among the lowest in South America. The recent sharp depreciation in BRL does, however, increase the real value of the debt payments.

A manageable and decreasing current account deficit. The deficit stood at 2.7% of GDP in 2019, although is set to end 2020 relatively balanced, having posted continuous positive flows between April and September.

Depreciation in FX does not seem to be filtering through to materially higher inflation, so an inflationary spiral in which currency depreciation feeds on itself seems unlikely.

Given the above supportive factors, and our view that the currency is very cheap at current levels, we do not think that a continued sell-off in the real at the rate witnessed since the onset of the crisis is likely in the long-term. We are instead continuing to pencil in a recovery for the currency against the dollar through to the end of 2021, and think that Brazil’s solid macroeconomic fundamentals should allow the currency to successfully bounce back once the worst of the crisis is over.

The main issue for the real is, of course, the extent to which Brazil is able to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus. An inability to do so relative to most of the rest of the world, and subsequent economic damage that this would cause, presents itself as a significant downside risk to our outlook.

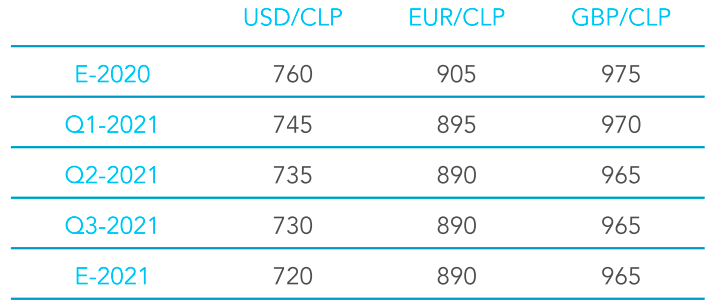

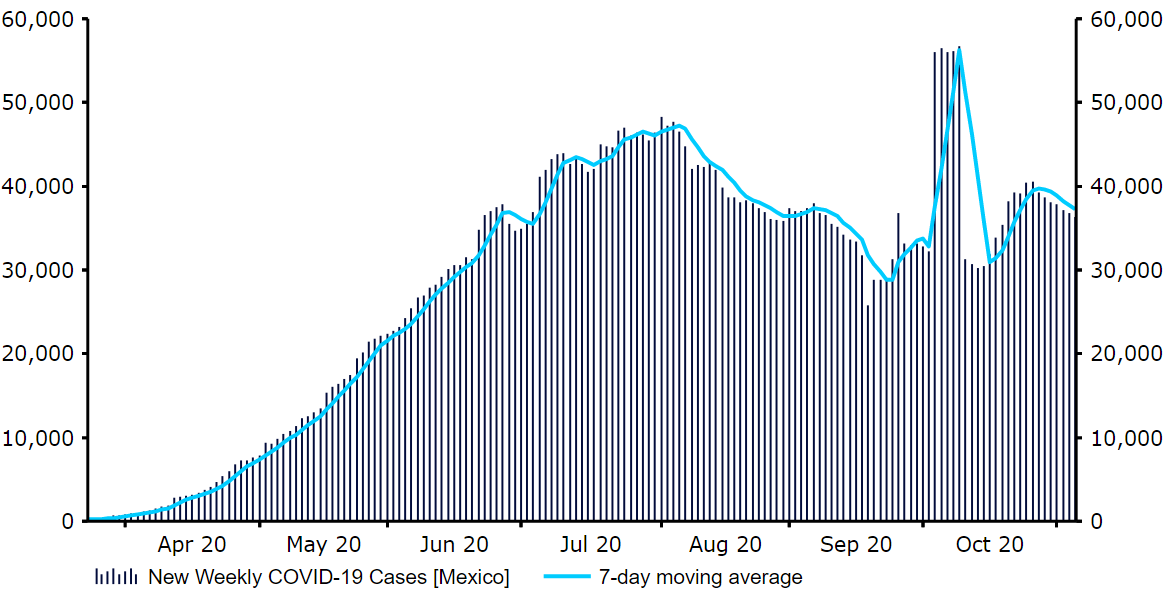

Chilean Peso (CLP)

The Chilean peso (CLP) has continued to rebound strongly since our last Latin America update.

CLP has been one of the more resilient emerging market currencies since the depths of the COVID-19 market panic earlier in the year. The peso has appreciated by more than 15% since falling to an all-time low in March, ensuring that it is now trading roughly where it was versus the US dollar since the beginning of the year. This puts the Chilean peso as the best performing currency in the Latin American region since the start of 2020.

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 28/10/2020

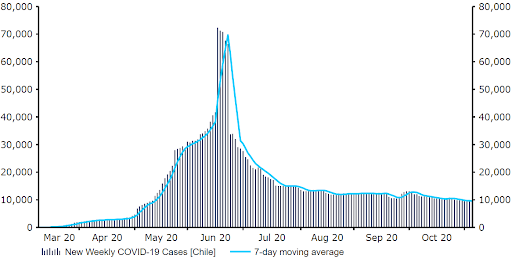

The relative resilience of CLP, particularly since the height of the general market panic in March and April, has defied the aggressive spread of the COVID-19 virus in Chile. Chile has been one of the worst affected countries in the world to the virus, with reported cases there now around the 520,000 mark (27,000 cases per 1M people). As a percentage of the total population, the country currently has the seventh highest number of COVID deaths per capita in the world.

High levels of infection are almost certainly a consequence of the less strict containment measures imposed by the Chilean government at the beginning of the crisis, as the country did not impose a national lockdown. Regional lockdowns have instead been implemented, notably across parts of the capital Santiago, along with a nationwide nighttime curfew. Encouragingly, however, there has been no signs of a second wave of infection just yet, with the moving average of new cases relatively flat since the beginning of July despite a doubling in testing during that time. This suggests that the regional shutdown measures appear to have had at least some positive impact on containing the virus’ spread.

Figure 5: Chile New Weekly Reported COVID-19 Cases (March ‘20 – October ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 28/10/2020

Similarly to its neighboring Peru, the Chilean government has had plenty of fiscal wriggle room to provide financial support to the domestic economy. The government has unveiled more than $30 billion in stimulus measures (greater than 12% of GDP), which place a heavy focus on income support and worker subsidies. This impressive financial response appears to have calmed some of the political unrest surrounding rising costs of living and high inequality that was triggered following the subway fare hike in October last year. The delayed referendum held at the end of October yielded an overwhelming majority in favour of rewriting Chile’s constitution. This, we believe, is an encouraging step in the right direction towards ending the political unrest that had placed a significant risk premium on the peso.

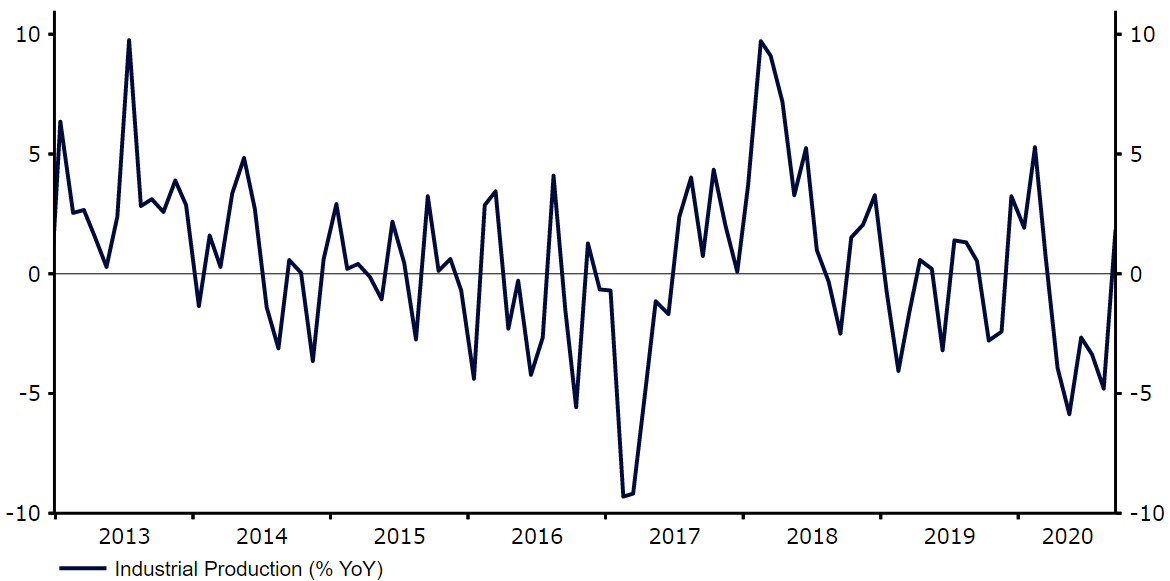

The less strict containment measures imposed in Chile allowed the Chilean economy to outperform many of its peers during the initial few months of the crisis period. After a decade-high 3% QoQ expansion in the first quarter of the year, the country’s economy contracted by 13.2% in Q2. While this marked the economy’s largest downturn on record, it represents a less violent contraction than that experienced by most of its Latin American peers, notably Peru. Importantly for Chile, the world’s largest producer of copper, authorities have managed to keep up activity in the industrial and mining sectors. Output data, including industrial (Figure 6), mining and steel production have held up much better during the pandemic period than in many other neighbouring Latin American countries. Improved copper demand from China following an economic rebound there should also help support activity, as does the rebound witnessed in copper prices that are now around their highest level since mid-2018.

Figure 6: Chile Industrial Production (2013 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 28/10/2020

We remain optimistic regarding the Chilean peso. While the aggressive spread of the virus in the country is a cause for concern, the relative outperformance of the Chilean economy, large-scale fiscal response and the passing of the constitutional reform in October should continue to support the currency, in our view. This, we believe, should allow the peso to post decent gains against the US dollar in 2021. Real interest rates in negative territory (around -2%) does, however, provide a downside risk to these forecasts.

Colombian Peso (COP)

The Colombian peso (COP) has remained resilient versus the US dollar since our last Latin American forecast revision.

The peso shed around one-fifth of its value in a three-week period during the height of the market panic in March (Figure 7), extending its year-to-date losses to over 20%. The currency roared back sharply after falling to an all-time low, leading the gains among currencies in the region. COP has spent almost all of the past four months within the 3600-3800 range, although it still remains one of the worst performers in the emerging market universe year-to-date.

The sell-off in the peso earlier in the year was exacerbated by the dramatic collapse in global oil prices, to which the Colombian economy is closely linked. The peso has historically followed a remarkably similar trend to that of global oil prices, given that oil accounts for around two-thirds of Colombia’s overall export revenue. Global Brent Crude oil prices crashed below $20 a barrel in April, although have since recovered to around $40 a barrel. This is just below Colombia’s projected breakeven oil price of $45 a barrel. Colombia’s oil production increased for the third straight month in August, although remained 16% lower than the same period a year previous, with a return to pre-pandemic levels appearing some way off.

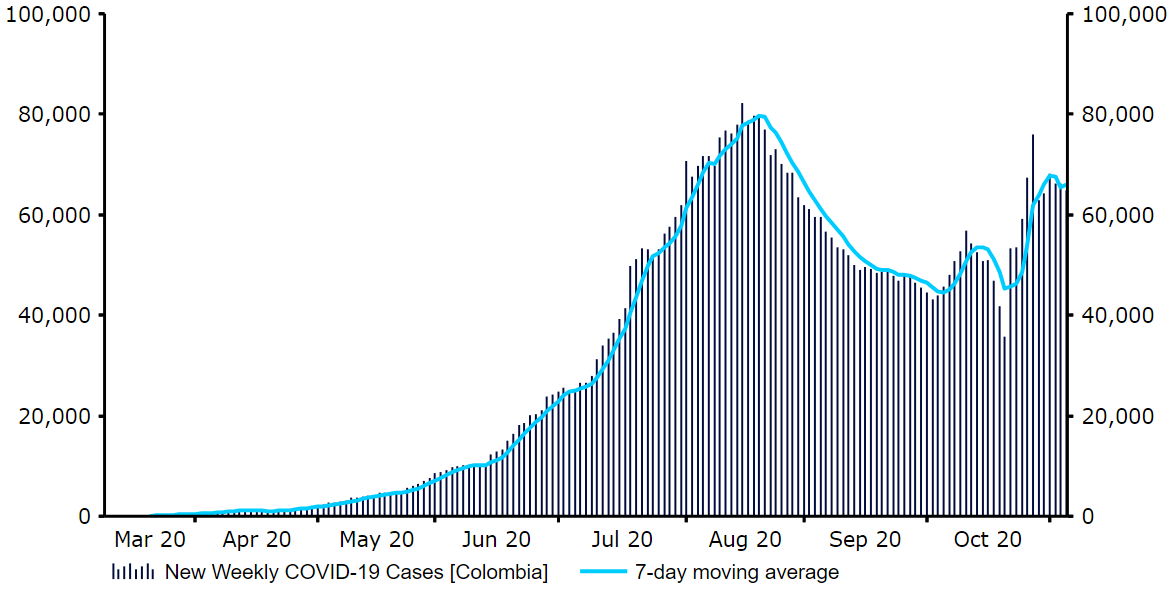

A worrisome development since our most recent update in July has been the sharp increase in COVID-19 cases witnessed in Colombia, albeit cases have stabilised since their peak in August. Following a rather dramatic threefold increase in testing between mid-June to early-August, new daily case numbers rose aggressively, peaking at more than 10,000 per day. This ensures that Colombia now has the ninth highest total number of confirmed cases of the virus in the world, despite the still limited levels of testing conducted (103 per 1,000 people versus 460 in the US). The number of reported deaths caused by the virus per 1,000 tests conducted has also risen more rapidly than its peers during this time, albeit it is not yet at disproportionate levels relative to other countries in the region. These large virus caseloads have, we believe, been behind at least some of the recent weakness in COP that has seen it underperform almost all of its regional peers in the last few months.

Figure 8: Colombia New Weekly COVID-19 Cases (March ‘20 – October ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 23/10/2020

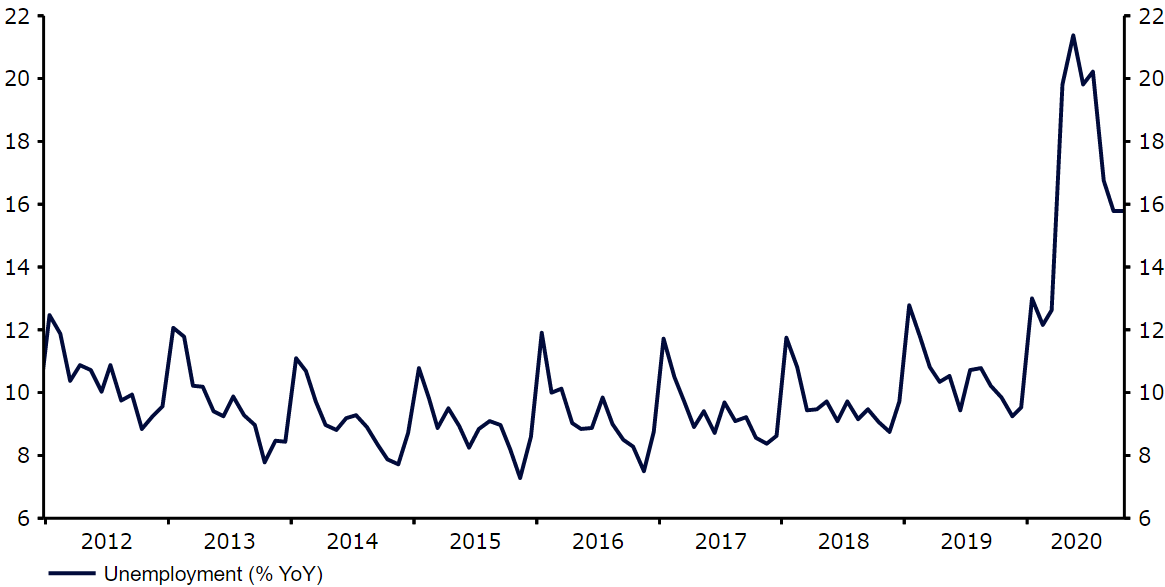

The strict social distancing measures and national lockdown imposed earlier in the year triggered a record 14.9% contraction in the Colombian economy in the second quarter of the year. Worst case scenarios for economic activity do, however, appear to have been prevented, with the relatively well executed handling of the pandemic allowing most indicators to bounce back well. This recovery has been most notable in retail sales and industrial production, albeit both remain well below pre-pandemic levels. We expect the Colombian economy to mildly outperform its peers in the coming months. A sharp increase in unemployment presents a downside risk to this view, although the jobless rate did fall relatively sharply in August to 16.8% from more than 20% (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Colombia Unemployment Rate (2013 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 28/10/2020

While the scale of the fiscal response from the Colombian government was relatively limited at the beginning of the crisis, the country’s government has announced plans to increase the country’s 2021 budget by 13.4%. This would allow a debt financed increase in public sending in order to aid the recovery. The suspension of the country’s ‘Fiscal Rule’ designed to rein in the deficit earlier in the year has also been greeted positively by the market and will be welcome news for a labour market that has been battered by the lockdown and oil price collapse. There also remains additional room for further central bank cuts, in our view. Interest rates were cut again by another 25 basis points by the Central Bank of Colombia during its September meeting in a narrow 4-3 vote, taking the main base rate to 1.75%. The rather dramatic fall witnessed in inflation has provided room for the aforementioned cuts, although with headline price growth rising back to 2% in September, there may be limited room for more easing given that real rates are now below zero.

We remain largely optimistic regarding the Colombian peso. The country’s fairly solid fundamentals, notably high FX reserves equivalent to twelve months of import cover and low external debt (40% of GDP), should continue to support the currency, in our view. The possibility of additional fiscal stimulus is also a positive. The current account deficit also looks set to narrow in 2020, having risen to more than 4% of GDP last year, and remains almost completely financed by high quality FDI flows. We therefore forecast continued mild gains for the peso against the US dollar in 2021.

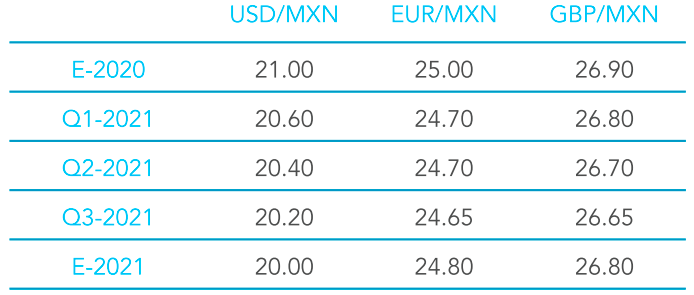

Mexican Peso (MXN)

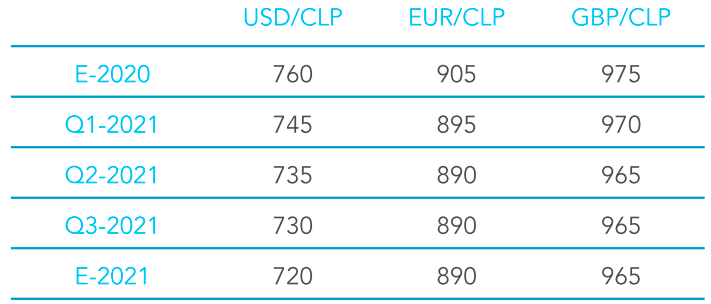

The Mexican peso (MXN) was one of the worst-performing currencies in the world in March and April. MXN shed around one-third of its value in the three weeks or so from the beginning of March, sending the peso to an all-time low north of 25 to the US dollar.

The currency rallied back sharply in the second and third quarters of the year, appreciating to its strongest position since early-March in September as investors once again favoured high risk assets. The peso sold-off again in late-September, although it is now back trading just above the 20 level to the dollar following the US election.

Figure 10: USD/MXN (November ‘19 – November ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 28/10/2020

One of the main reasons for the currency’s move lower earlier in the year was the peso attractiveness from a carry trade perspective. Such currencies tend to experience larger sell-offs during intense ‘risk off’ modes, as investors unwind long positions and exit these carry trades en masse. It is for this reason that we think MXN has been one of the better performers in the EM universe since the peak of the market trough, albeit its appeal as a carry trade strategy has lessened since the onset of the pandemic. Banxico has cut interest rates aggressively, lowering its main rate by a total of 300 basis points to 4.25%. The decision to cut rates at the most recent central bank meeting in September marked the eleventh straight meeting of cuts. The 25 basis point reduction was, however, less than the 50 basis points of cuts delivered in the five meetings previous, in part due to higher domestic inflation. Further cuts present a possible downside risk to the peso, particularly given Mexico’s positive carry has long been one of the currency’s key appeals to foreign investors.

A further cause for concern among currency traders has been the Mexican government’s unwillingness to spend money to protect the economy. Unlike most of the world, Mexico’s President, López Obrador, has resisted pressure to loosen fiscal policy. Obrador has voiced concerns over taking on additional debt, despite the country’s relatively low public debt-to-GDP levels. As things stand, Mexico is set to increase its spending by less than 1% of GDP this year – a very modest level compared to most of its peers.

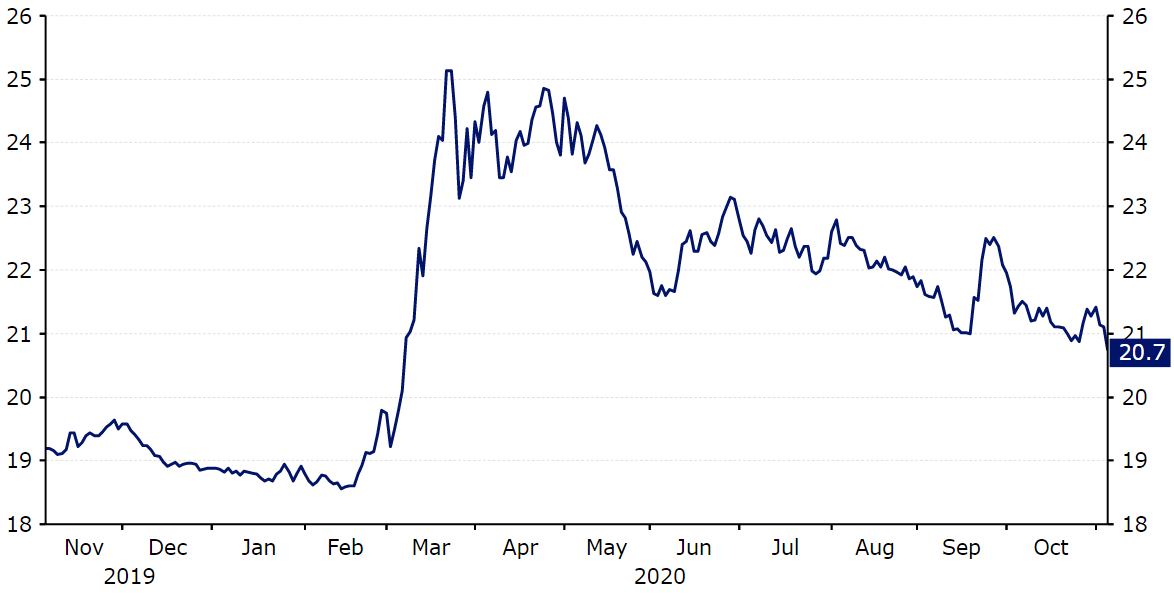

Similarly to many of its regional peers, the spread of the COVID-19 virus has become much more aggressive in Mexico than at the time of our most recent Latin America forecast revision. Despite conducting among the lowest levels of testing per capita in the world, Mexico now has the tenth highest number of confirmed cases of the virus. Mexico’s ratio of virus deaths per 1,000 people is also comparable to that in the US, despite the country only conducting levels of testing that equate to around 4% of that undertaken in America. This high level of infection may be due to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador being slow to impose lockdown measures and then the early phased re-opening in May amid fears about the country’s flagging economy.

Figure 11: Mexico New Weekly COVID-19 Reported Cases (April ‘20 – Nov ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 25/10/2020

Even prior to the current crisis, the country’s economy had been under pressure, contracting in six of the eight quarters leading up to the pandemic. Since the beginning of the pandemic, activity data has unsurprisingly deteriorated further, with the 17.1% plunge in activity in the second quarter of the year one of the deepest downturns in the region. This dismal economic performance has further worsened satisfaction with President Obrador who has seen a dramatic collapse in his approval rating since taking office. The recovery since then has not been quite as rapid as witnessed among some of its peers – retail sales for instance remained in excess of 10% smaller than a year previous in August. We think that much of this slower recovery has to do with the mass job lay-offs in Mexico. Approximately 12 million jobs were lost during the height of the lockdown during March and May alone (around 21% of the total labour force) amid a lack of support from the Mexican government.

That said, we continue to think that the peso is in a reasonable position to post modest gains versus the US dollar next year. Mexico’s external position has improved, with the current account balance largely flat last year and expected to remain around its healthiest position relative to GDP since the late-1980s this year. The country’s external debt level is low compared to many of its regional peers at approximately 30% of GDP. Real interest rates also remain positive, for now, although a sharp jump in consumer inflation and recent policy easing from the central bank means that the real rate of return on Mexican assets has declined rather sharply since prior to the pandemic.

Figure 12: Mexico Real Interest Rates (2007 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 25/10/2020

We think that there are enough supportive factors to ensure that the peso should be able to post decent gains against what we think will be a broadly weaker US dollar in the next twelve months or so. The unwillingness of the Mexican government to support the economy through fiscal spending does, however, ensure that we think these gains may be slightly less pronounced than they otherwise would have been.

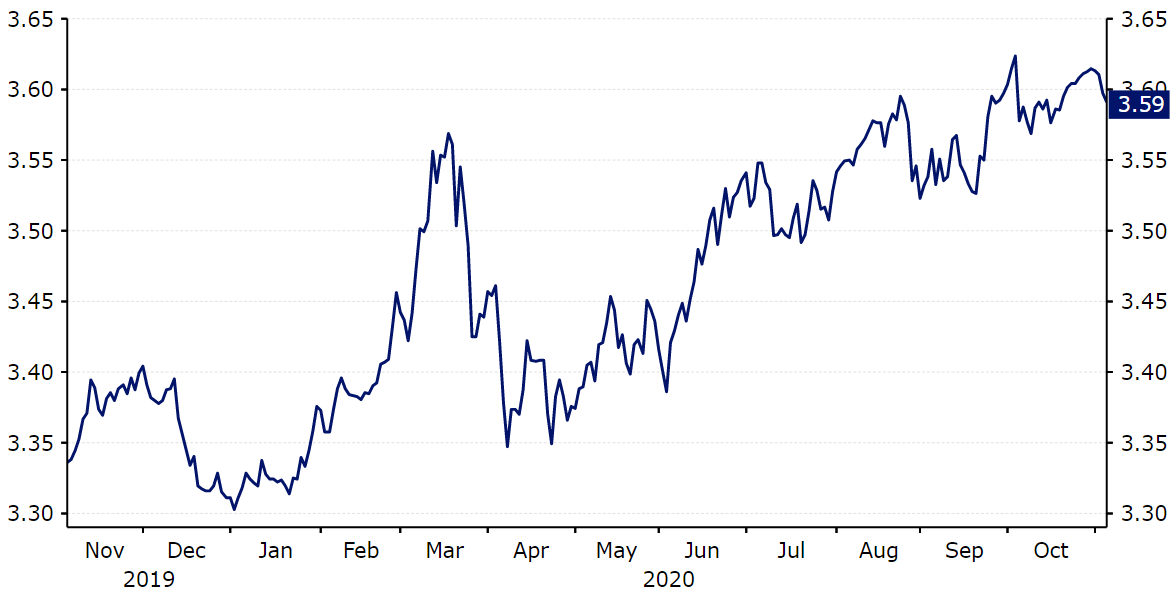

Peruvian New Sol (PEN)

The Peruvian new sol (PEN) was one the best performing currencies in the Latin America region during the peak of the crisis earlier in the year.

The new sol fell to a nineteen year low at the height of the market panic in March, before erasing the majority of its losses amid an aggressive stimulus injection from the Peruvian government. Since mid-June PEN has, however, begun to sell-off again, collapsing to fresh lows in late-August at a time when most other emerging market currencies have rallied amid largely ‘risk on’ trading. We think that this idiosyncratic move has been triggered, at least in part, by the very aggressive spread of the virus in the country. This ensures that the currency is now trading appropriately 8% lower since the turn of the year (Figure 13), despite ongoing intervention from the Central Reserve Bank of Peru.

Figure 13: USD/PEN (November ‘19 – November ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 28/10/2020

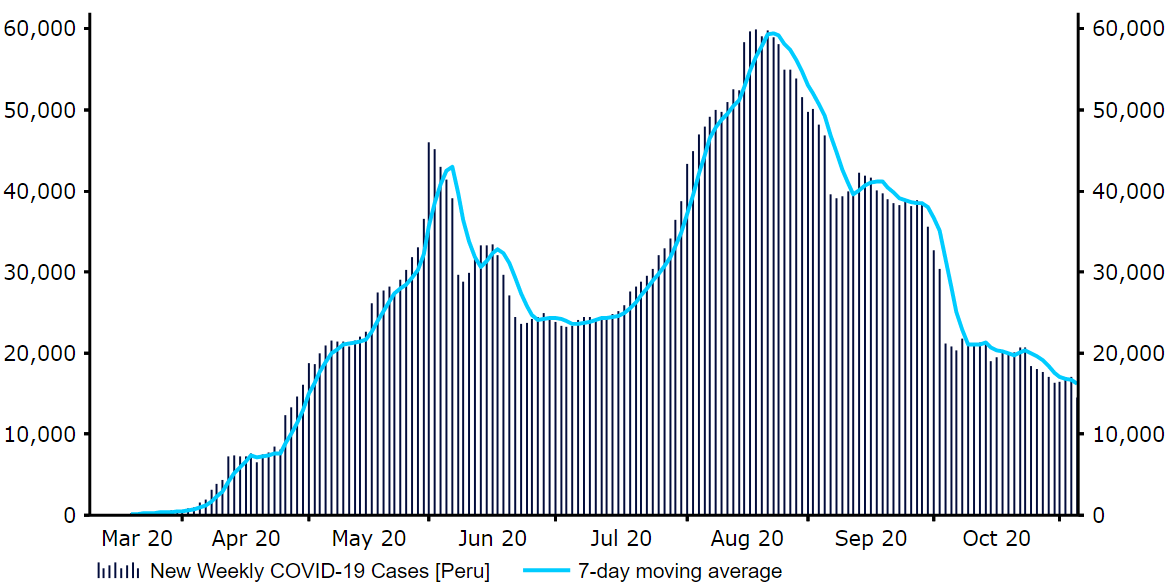

Peru has been one of the worst affected countries in the world by the pandemic, so far reporting more than 900,000 cases at the time of writing – the highest in Latin America terms of cases per capita according to worldometers (27,600 cases per 1 million people). The number of new confirmed cases peaked in August, partly due to greater levels of testing, although have since stabilised. Far more concerning is that Peru now has the third highest number of deaths per capita in the world (1.05 per 1,000 people), behind only the small nation of San Marino and Belgium. An inadequate health system, including unequal access to health care and a shortage of medical supplies, has left some regions ill-equipped to deal with the pandemic. Corruption has also reportedly left many of the most vulnerable without financial assistance, causing large numbers to flaunt the strict lockdown measures. A raft of inquiries have been opened up since the beginning of the national lockdown in March, with most looking into whether officials have embezzled funds designed to pay for aid or protective equipment.

Figure 14: New Weekly COVID-19 Cases [Peru] (March ‘20 – November ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 24/10/2020

With low levels of government debt (27% of GDP) and a vast hoard of savings, the Peruvian government has been in the enviable position to be able to pump a huge amount of stimulus into the economy since the onset of the crisis. Authorities in Peru have unveiled mammoth and wide-ranging stimulus programmes equivalent to almost 17% of the country’s GDP – the largest in the region. This includes spending on healthcare, cash handouts and targeted relief for those worst affected areas of the economy, such as tourism. While this has helped support local assets, the high levels of corruption at the municipal level ensures that efforts to provide financial aid to those that most need it have not been entirely successful.

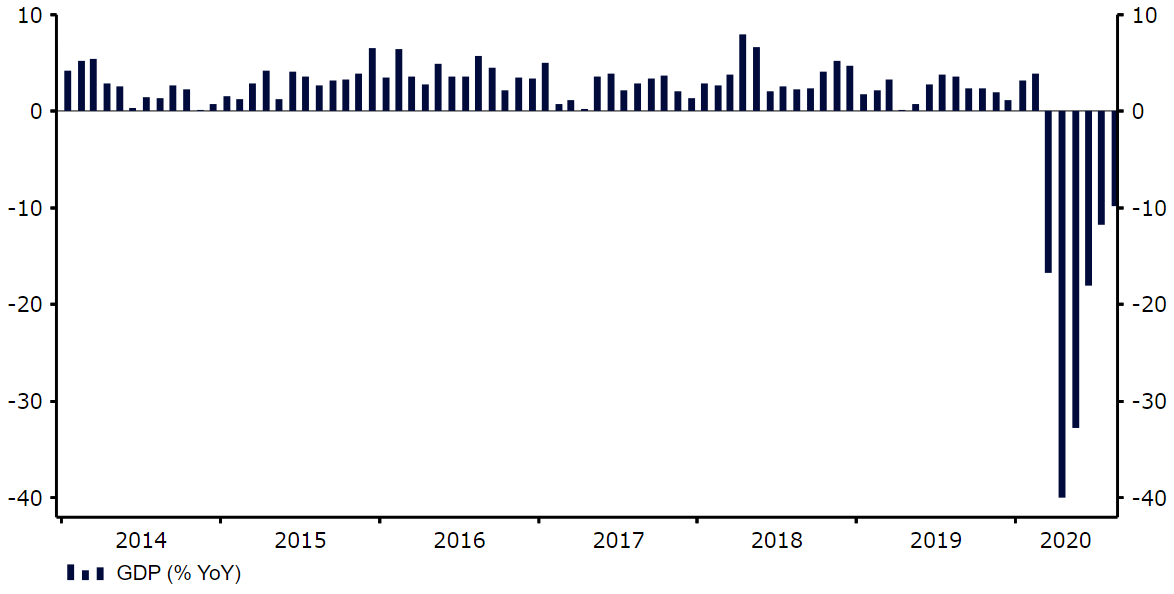

Amid the drastic measures to contain the spread of the virus, the impact on the Peruvian economy has been devastating, highlighting the need for the aforementioned stimulus. Peru’s economy contracted by 27.2% QoQ in the second quarter of 2020 – by far the worst downturn of all the countries in the region and one of the largest in the world. The downturn was due in large part to one of the strictest lockdowns in the region, with many of the smaller services companies plunged into bankruptcy due to the collapse in activity. This triggered a sharp decrease in active employment, down 40% in the second quarter from a year previous.

Figure 15: Peru GDP Growth Rate (2014 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 24/10/2020

While the aggressive COVID spread in Peru presents a downside risk to the new sol, we believe that there remain a number of undoubted positives for the currency. The sell-off in PEN since June has created a rare divergence in the currency with that of global copper prices, to which the Peruvian economy is heavily linked. London Metal Exchange (LME) copper prices have continued to rise at a steady pace since tumbling to a more than four-year low in March and are now back above US$6,500 per tonne. Should this uptrend in copper prices continue, we think that we would likely begin to see this translated into a stronger new sol.

The Central Reserve Bank of Peru has also continued to intervene in the market in order to protect the currency, selling its FX reserves aggressively during the height of the turmoil in March and April. We think that it will continue to do so in the coming months, should PEN continue to sell-off towards undesirable levels. With foreign exchange reserves still equating to around 35% of GDP, we think that the central bank should have plenty of room to continue intervening in order to limit currency fluctuations. Peru’s current account deficit also looks very manageable so far this year, having stood at just 1.5% of GDP last year. A combination of emigrant remittances and foreign direct investment should be sufficient to cover this deficit. The return of real interest rates back into negative territory for the first time since 2016 after 200 basis points of central bank cuts earlier in the year does, however, present a downside risk to the new sol.

Given the ample room available for continued central bank intervention and additional fiscal spending on top of the sizable measures already announced, we think that the new sol is well placed to rebound against the US dollar from current levels. We think the central bank should then have no problem in maintaining stability in the USD/PEN exchange rate around the 3.30 level over the longer-term. We are, however, revising our short-term forecasts slightly higher.