Latin America FX Forecast Revision – July 2020

( 17 min )

- Go back to blog home

- Latest

Find below our latest analysis of the Latin America currencies: Brazilian Real (BRL), Mexican Peso (MXN), Chilean Peso (CLP), Peruvian New Sol (PEN) and Colombian Peso (COP).

The Brazilian real (BRL) has been one the worst performing major currencies in the world since the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus turned it into a full-blown pandemic.

The currency has lost around one-fifth of its value versus the US dollar since the beginning of March (Figure 1), as investors flocked to low beta assets and sold those deemed as higher risk. This sell-off sent the currency to its lowest ever level at just shy of 6 to the USD, although it has since recovered some of these losses.

Figure 1: USD/BRL (July ‘19 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

Ongoing political unrest in Brazil and criticism of authorities’ handling of the pandemic has significantly soured sentiment towards the real so far in 2020 and has been behind much of the currency’s underperformance. Far-right President Jair Bolsonaro has, like many of his predecessors, faced allegations of corruption in the last few months that have resulted in calls for his impeachment.

Until recently, investors were compensated for Brazil’s heightened political risk premium by the country’s very high real interest rates, which peaked at almost 8% in 2017. A series of interest rate cuts from the Central Bank of Brazil so far this year in response to the crisis has, however, significantly lowered the currency’s appeal. Rates have been slashed by a total of 200 basis points since the onset of the pandemic to 2.25%, which has significantly dented Brazil’s appeal from a carry trade perspective.

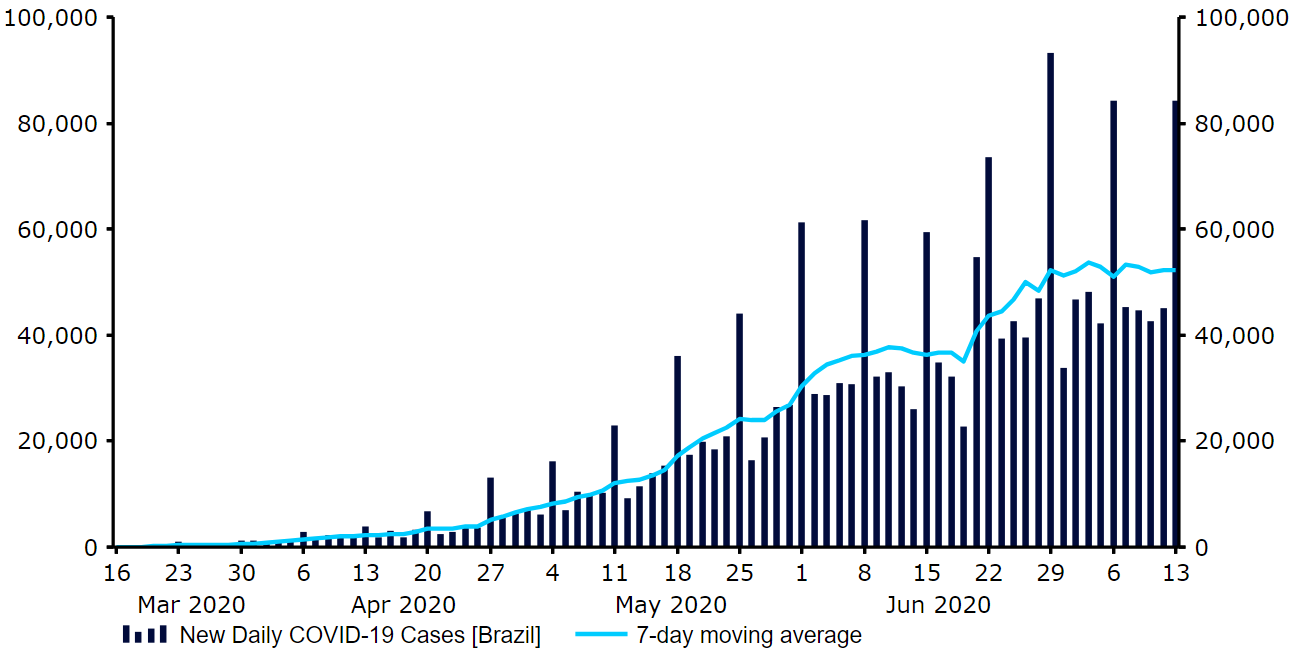

Even more troubling for investors has been the President’s approach to dealing with the COVID-19 virus outbreak. Bolsonaro has actively encouraged people to defy social distancing, ignore regional lockdown and partake in large gatherings. Brazil has racked up the second largest number of reported cases of the virus in the world and over 70,000 deaths at the time of writing – numbers that are likely much higher in reality due to very limited levels of testing. The country remains in the high growth phase of the virus, at a time when healthcare systems in some of the worst affected regions are already reportedly approaching full capacity. Reports that the majority of the population in some of Brazil’s largest cities, including Sao Paulo, are ignoring isolation orders is unlikely to help suppress the spread of the virus at the rate that we have witnessed across much of the rest of the world. An inability to rein in the number of new infections could lead to an even more severe recession in Brazil this year, in our view.

Figure 2: New Daily COVID-19 Cases [Brazil] (March ‘20 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

There is some good news in Brazil’s solid macroeconomic fundamentals. From a fundamental perspective, we think BRL is one of the better placed EM currencies to weather additional losses:

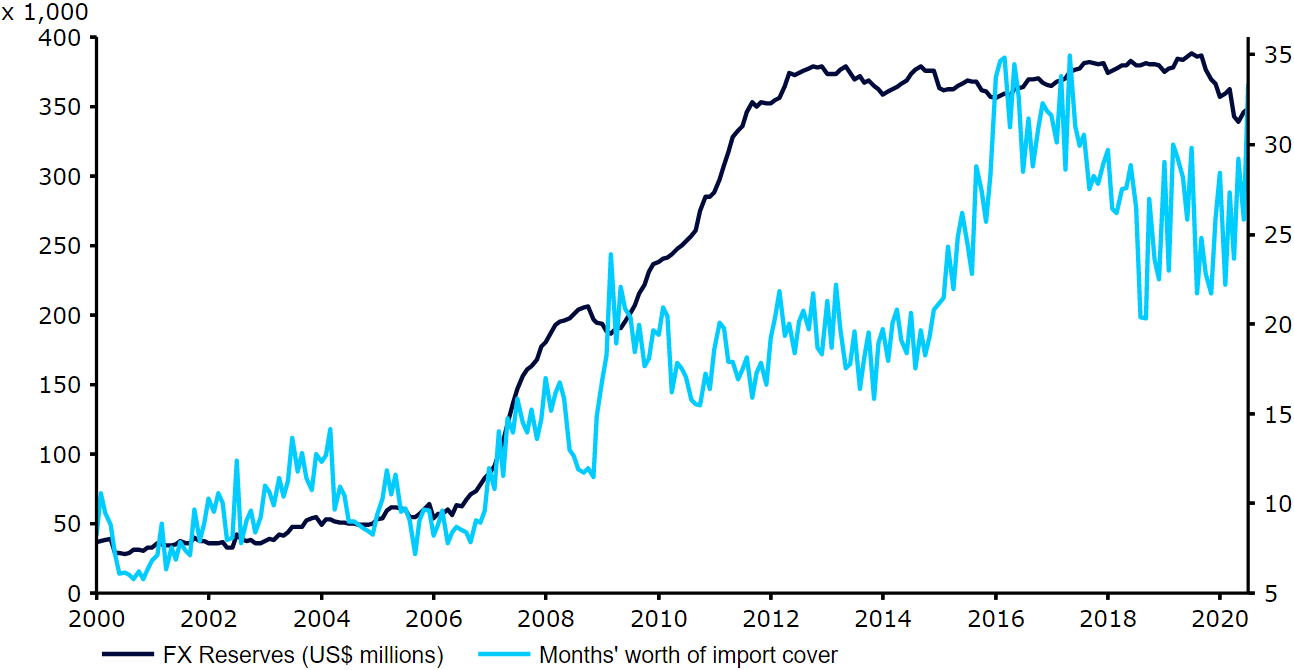

High FX reserves that equate to almost 30 months’ worth of import cover. This is an ample level of ammunition for the Central Bank of Brazil to successfully intervene in the market in order to reverse the currency’s sell-off. Central bank President Roberto Campos Neto stated in May that the bank had plenty of room to intervene and may step up its efforts to support the currency, should it deem necessary.

Figure 3: Brazil FX Reserves (2000 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

Low levels of external debt that equate to approximately 18% of GDP – among the lowest in South America. The recent sharp depreciation in BRL does, however, increase the real value of the debt payments.

A manageable, albeit rising, current account deficit. This deficit increased to 2.7% of GDP in 2019, although remained comfortably financed by foreign direct investment (FDI).

Depreciation in FX does not seem to be filtering through to higher inflation, so an inflationary spiral in which currency depreciation feeds on itself seems unlikely.

Given the above supportive factors, and our view that the currency is very cheap at current levels, we do not think that a continued sell-off in the real at the rate witnessed since the onset of the crisis is likely in the long-term. We are instead continuing to pencil in a recovery for the currency against the dollar through to the end of 2021, and think that Brazil’s solid macroeconomic fundamentals should allow the currency to successfully bounce back once the worst of the crisis is over. The main issue for the real is, of course, the extent to which Brazil is able to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus. An inability to do so relative to most of the rest of the world, and subsequent economic damage that this would cause, presents itself as a significant downside risk to our outlook.

Chilean Peso CLP

The Chilean peso (CLP) has been one of the more resilient currencies in the Latin America region since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, although it is currently still trading comfortably lower year-to-date versus the US dollar.

Since the beginning of the year, the currency has lost approximately 5% of its value against the dollar, having recovered over a half of its losses since the peak in late-March (Figure 4).

Figure 4: USD/CLP (July ‘19 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

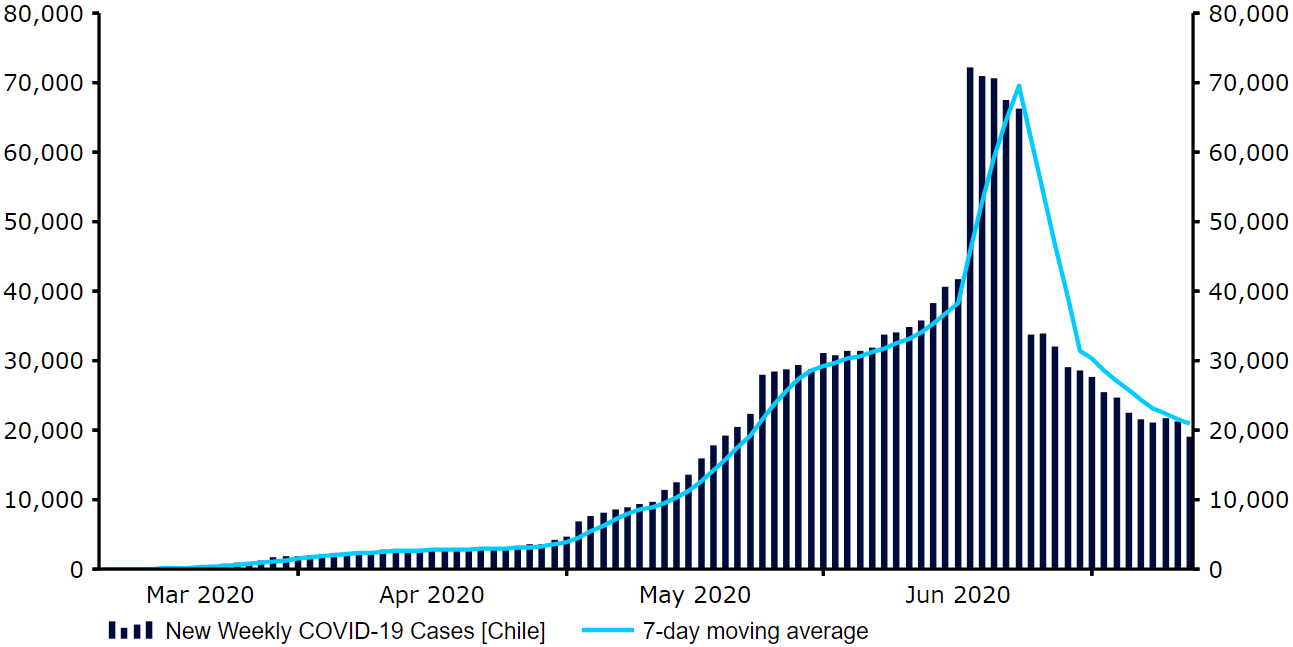

The relative resilience of CLP, particularly since the height of the general market panic in March and April, has defied the aggressive spread of the COVID-19 virus in Chile. Chile has been one of the worst affected countries in the world to the virus, with reported cases there now in excess of the 300,000 mark. As a percentage of the total population, the country currently has the fifth highest rate of infection in the world and the worst in the Latin America region.

This is almost certainly a consequence of the less strict containment measures imposed by the Chilean government since the beginning of the crisis, with the country one of the minority in the world to not impose a national lockdown. Encouragingly, however, the number of new daily cases and deaths caused by the virus have begun to ease, with the regional shutdown measures appearing to have at least some positive impact on containing the virus’ spread.

Figure 5: Chile New Weekly COVID-19 Cases (March ‘20 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

Similarly to its neighboring Peru, the Chilean government has had plenty of fiscal wriggle room to provide financial support to the domestic economy. The government has unveiled more than $30 billion in stimulus measures (greater than 12% of GDP), which place a heavy focus on income support and worker subsidies. This impressive financial response appears to have calmed some of the political unrest surrounding rising costs of living and high inequality that was triggered following the subway fare hike in October last year. A constitutional referendum was due to be held in April, although this has now been delayed until October due to the pandemic.

The political uncertainty associated with the unrest continues to place a risk premium on the peso, although we think that the referendum should help towards ending the uncertainty.

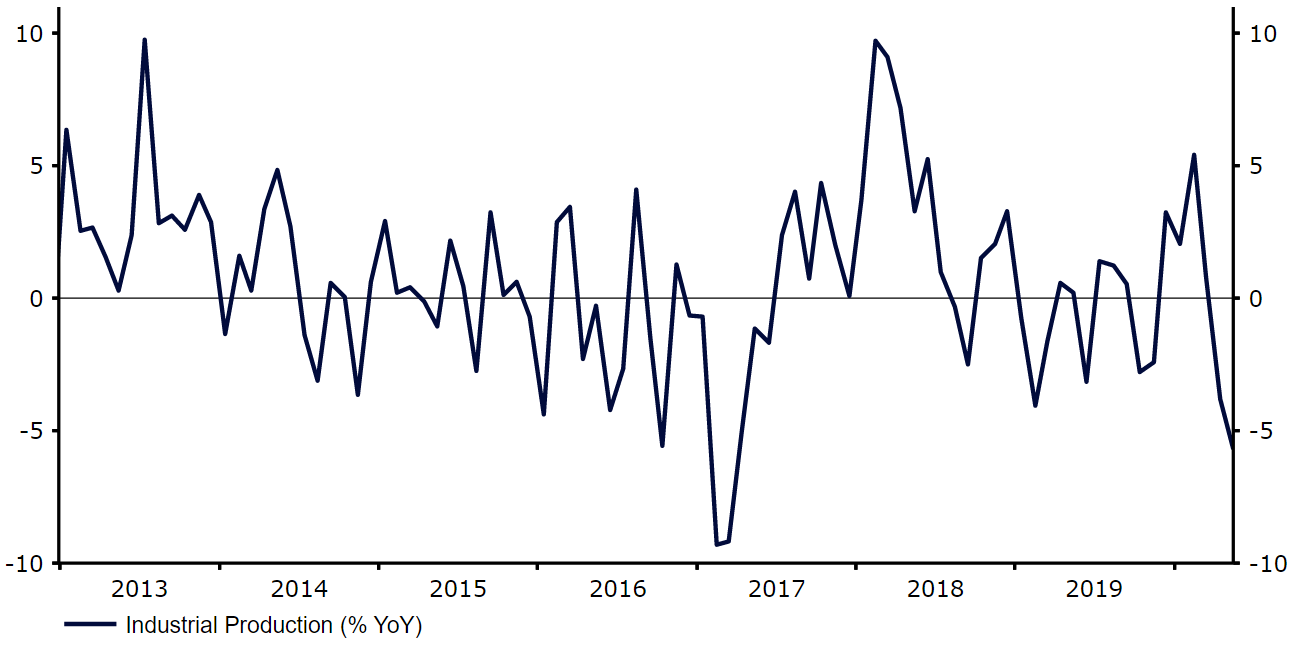

The less strict containment measures imposed in Chile has allowed the Chilean economy to outperform many of its peers during the crisis period – an outperformance we think can be attributed to at least some of the resilience in the peso. The economy actually posted a surprisingly high expansion of 3% quarter-on-quarter in Q1, its fastest rate of growth in over a decade. This does, however, have much to do with the base effect after the previous quarter’s violent contraction that was triggered by the mass protests in the country. More up-to-date measures of economic activity have deteriorated, notably retail sales that posted around 30% year-on-year contractions in both April and May. Output data, including industrial (Figure 6), mining and steel production has, however, held up much better during the pandemic period and has proved generally more resilient than in many other neighbouring Latin American countries.

Figure 6: Chile Industrial Production (2013 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

We remain optimistic regarding the Chilean peso. While the aggressive spread of the virus in the country is undoubtedly a cause for concern, the relatively less strict containment measures and large-scale fiscal response ensure that we think the Chilean economy will continue to outperform many of its peers. This, we believe, should allow the currency to post decent gains against the US dollar this year. Real rates in negative territory and an increasing current account deficit do, however, provide downside risks to these forecasts.

Colombian Peso COP

The Colombian peso (COP) has roared back sharply since falling to an all-time low versus the US dollar during the height of the sell-off in emerging market currencies earlier in the year.

The peso shed around one-fifth of its value in the first three weeks or so of March (Figure 7), extending its year-to-date losses to almost 30% at one stage. It has, however, since led the gains among Latin American currencies, recovering the majority of these losses amid the general improvement in risk sentiment and move higher in oil prices. The Colombian peso has been the best performing currency in the world since it fell to its all-time low on 19th March.

Figure 7: USD/COP (July ‘19 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

The sell-off in the peso was exacerbated by the dramatic collapse in global oil prices, to which the Colombian economy is closely linked. The peso has historically followed a remarkably similar trend to that of global oil prices, given that oil accounts for around two-thirds of Colombia’s overall export revenue.

Global Brent Crude oil prices crashed below $20 a barrel in April, although have since recovered sharply to back above $43 a barrel on hopes of a faster-than-expected recovery in the global economy.

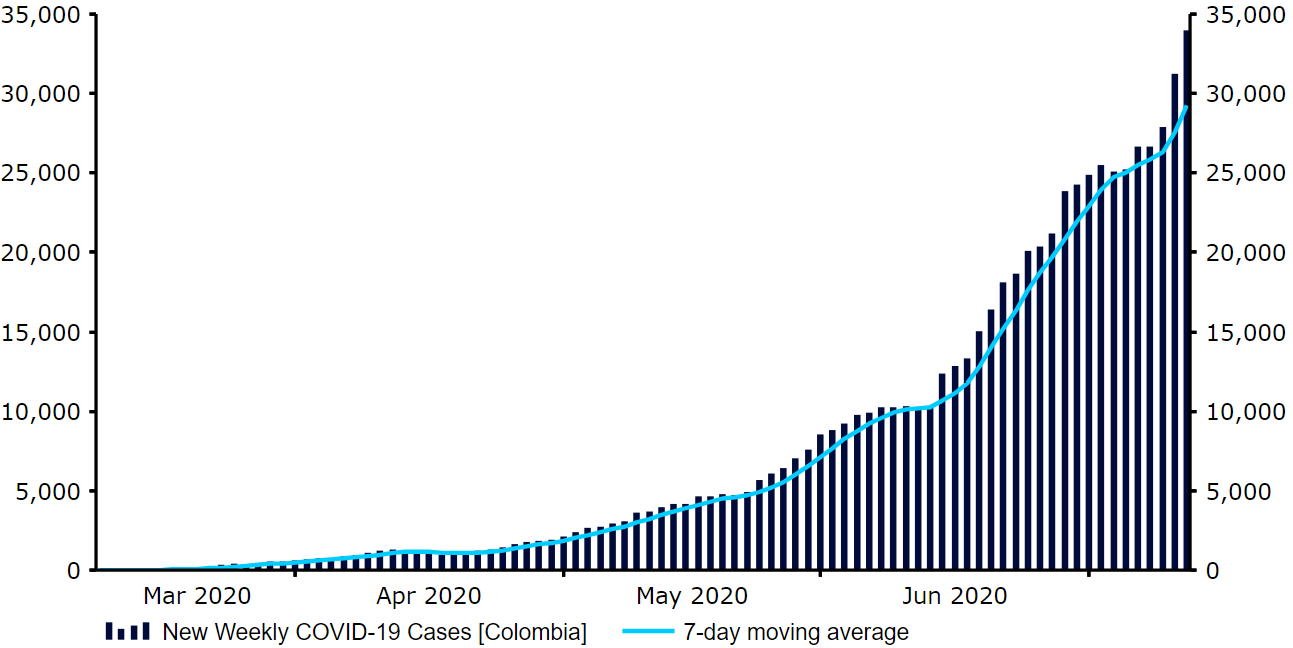

A less aggressive spread of the virus in Colombia relative to some of its neighbouring peers has also allowed COP to bounce back since the worst of the market panic. Colombia has reported approximately 130,000 cases of the virus at the time of writing. While this puts Colombia as the fourth worst affected country in South America, the number of cases per 1,000 people (2.96) is significantly lower than a country such as Brazil (8.8), which has carried out a similar amount of tests. The number of reported cases and deaths caused by the virus per 1,000 tests conducted have also been much lower in Colombia than most of the rest of the region. A significant cause for concern is, however, the fact that we have not yet seen any signs of an easing in the number of new daily cases of the virus in Colombia. Restrictions have been eased only gradually by the Colombian government, with the national lockdown extended until at least 1st August.

Figure 8: Colombia New Weekly COVID-19 Cases (March ‘20 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

Despite the national lockdown being imposed late in the first quarter of the year, Colombia’s economy contracted by 2.4% quarter-on-quarter in Q1, its largest downturn on record. Economic data for April indicated a much sharper contraction, notably the 42.5% collapse in retail sales and 26.7% drop in industrial production. We have, however, seen a general improvement in soft activity data since then, which provides reason for optimism. Colombia’s manufacturing PMI leapt back to a nine year high 54.7 in June, with business confidence also picking up from its lows.

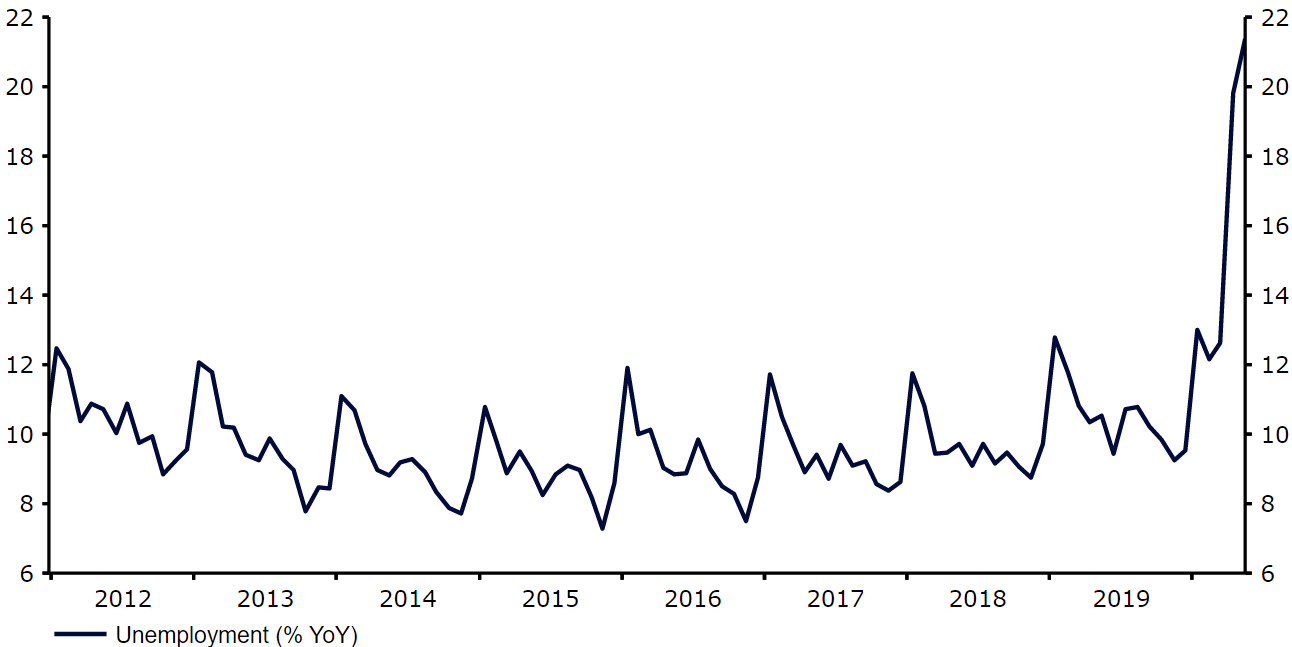

While the scale of the fiscal response from the Colombian government to deal with the crisis has so far been rather limited, the suspension of the country’s ‘Fiscal Rule’ designed to rein in the deficit suggests that more spending is on the way. This will be welcome news for a labour market that has been battered by the lockdown and oil price collapse – the jobless rate surged to a record high 21.4% in May (Figure 9). There also remains additional room for further central bank cuts, in our view. Interest rates were cut for the fourth consecutive Central Bank of Colombia meeting in June, with the base rate lowered by another 25 basis points to 2.5%. Two of the seven members voted for an immediate 50 basis point cut, suggesting that more easing may be on the way at upcoming meetings.

Figure 9: Colombia Unemployment Rate (2012 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

We remain largely optimistic regarding the Colombian peso. The country’s fairly solid fundamentals, notably high FX reserves equivalent to twelve months of import cover and low external debt (40% of GDP), should continue to support the currency, in our view. The possibility of additional fiscal and monetary stimulus should also continue to alleviate pressure on the Colombian economy as it continues to gradually unwind lockdown measures. A slight concern is the country’s growing current account deficit that rose to more than 4% of GDP last year, partly a result of the economic crisis in neighbouring Venezuela. The deficit does, however, remain almost completely financed by relatively high quality FDI flows. We therefore forecast continued gains for the peso against the US dollar this year and next.

Mexican Peso MXN

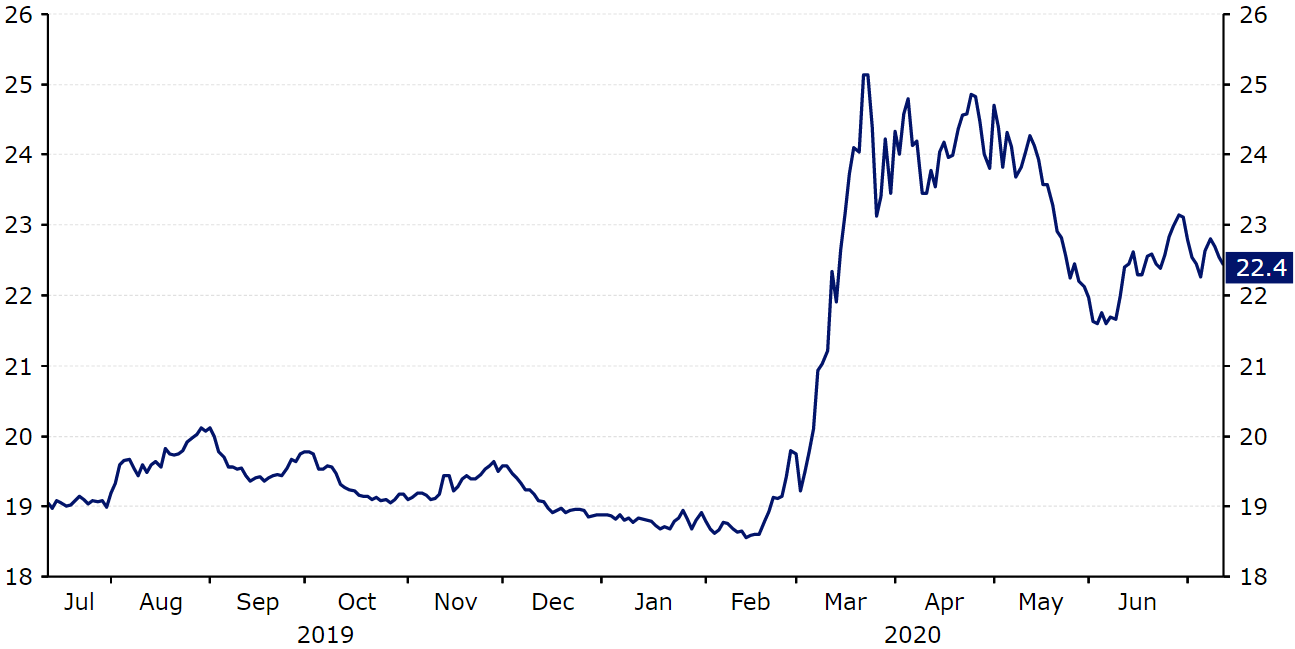

The Mexican peso (MXN) was one of the worst-performing currencies in the world at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in March and April.

MXN shed around one-third of its value in the three weeks or so from the beginning of March, sending the peso to an all-time low north of 25 to the US dollar. Since then, the currency has stabilised somewhat, although its rebound has been limited, with the peso still trading almost 20% lower year-to-date (Figure 10).

Figure 10: USD/MXN (July ‘19 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

A number of factors contributed to the large-scale depreciation witnessed in the peso at the onset of the pandemic. The currency’s attractiveness from a carry trade perspective also exacerbated the move lower, in our view, as investors began unwinding positions and exiting these carry trades en masse during the intense ‘risk off’ mode in March. Since the beginning of the pandemic Banxico has, however, cut interest rates aggressively, lowering its main rate by a total of 225 basis points to 5%.

The decision to cut rates at the most recent central bank meeting in late-June was a unanimous one, with the language in the statement leaving the door open to additional easing. This presents a possible downside risk to the peso, particularly given Mexico’s positive carry has long been one of the currency’s key appeals to foreign investors.

A further cause for concern among currency traders has been the Mexican government’s unwillingness to spend money to protect the economy. Unlike most of the world, Mexico’s President, López Obrador, has resisted pressure to loosen fiscal policy. Obrador has voiced concerns over taking on additional debt, despite the country’s relatively low public debt-to-GDP levels. As things stand, Mexico is set to increase its spending by less than 1% of GDP this year – a meagre level compared to most of its peers.

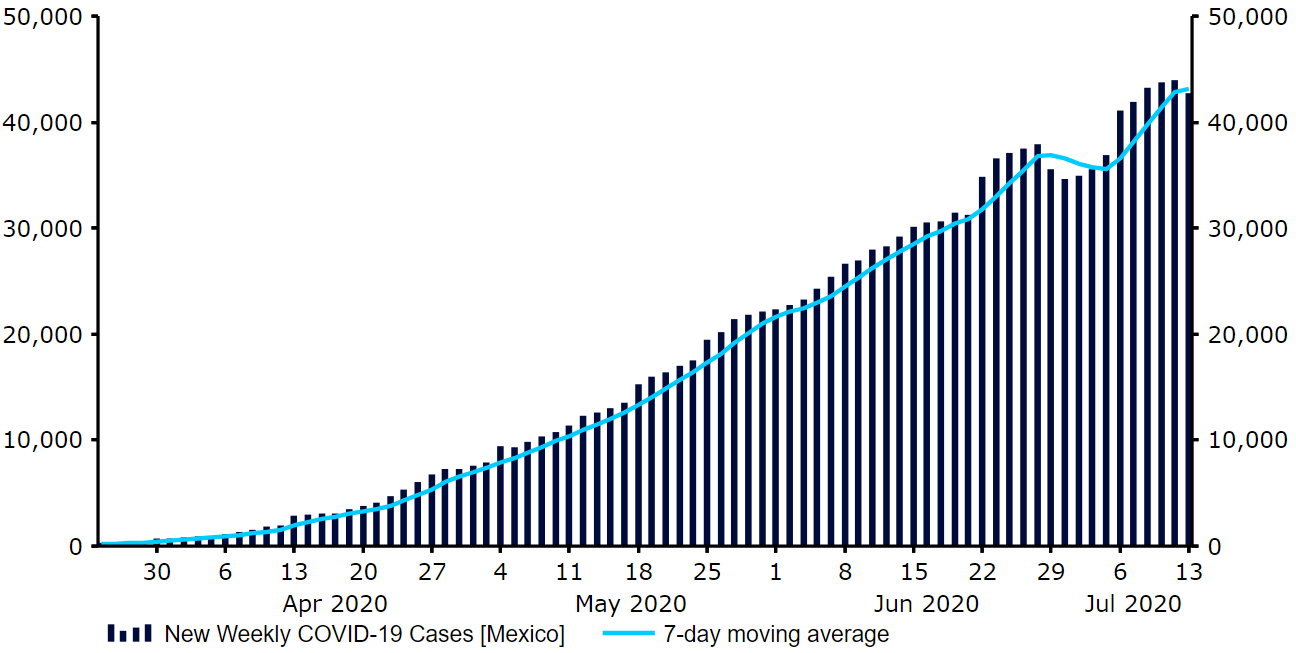

While the spread of COVID-19 has not yet been as aggressive in Mexico as some of its regional peers as a percentage of the population, the country remains in the high growth phase of the virus at the time of writing. New weekly cases have shown tentative signs that they may be easing, although there has thus far been no clear signs that the virus is yet to have peaked (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Mexico New Weekly COVID-19 Cases (March ‘20 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

There have, however, been serious doubts regarding the accuracy of these numbers, with a number of independent reports suggesting that the actual death toll could be much higher.

Despite the high and rising levels of new virus cases, authorities have begun to open-up Mexico’s economy in an attempt to alleviate further stress. Even prior to the current crisis, the country’s economy had been under pressure, contracting in six of the last eight quarters. Fears of a deep recession have amplified concerns that Mexico’s credit rating could be slashed to ‘junk’ territory in the coming months for the first time in almost two decades. Since the beginning of the pandemic, activity data has unsurprisingly deteriorated further, including a 25% contraction in industrial production and 22% drop in retail sales in April from the previous month. While the easing of lockdown measures should help in this regard, the inability of authorities to control the spread of the virus does add a potential risk to the peso.

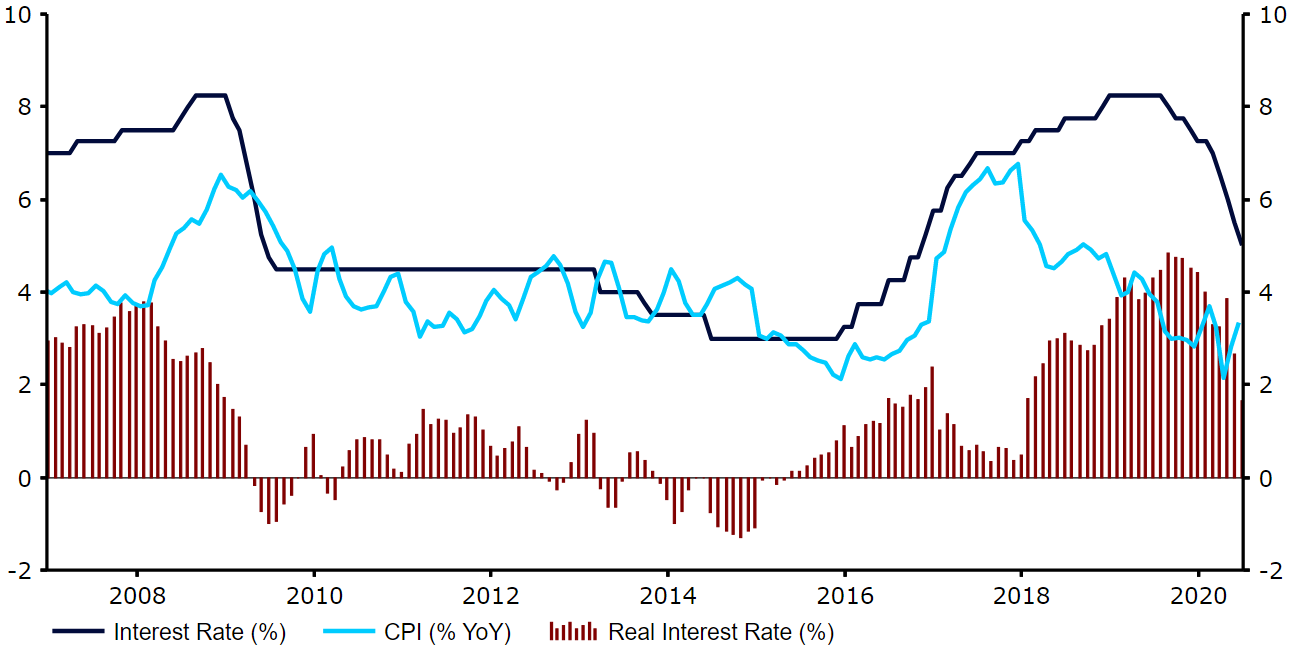

That said, we continue to think that the peso is in a good position to post reasonable gains versus the US dollar this year. We think that the sell-off induced by the pandemic has left MXN at undervalued levels that are not justified by the country’s economic fundamentals. Mexico’s external position has improved, with the current account balance largely flat last year and around its healthiest position relative to GDP since the late-1980s. The country’s external debt level is low compared to many of its regional peers at approximately 30% of GDP. Despite recent policy easing, the peso also remains one of the highest-yielding currencies in the Latin America region. With a weaker peso not yet filtering its way through to higher inflation, real interest rates remain firmly positive at approximately 2%. This should, we believe, continue to provide an attractive proposition to investors once the pandemic has eased.

Figure 12: Mexico Real Interest Rates (2007 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

We think that there are enough supportive factors to ensure that the peso should be able to post strong gains against what we think will be a broadly weaker US dollar this year. The unwillingness of the Mexican government to support the economy through fiscal spending does, however, ensure that we think these gains may be slightly less pronounced than they otherwise would have been.

Peruvian New Sol PEN

The Peruvian new sol (PEN) has been one the best performing currencies in the Latin America region since the onset of the crisis, though the currency is still currently trading lower versus the US dollar year-to-date.

The new sol fell to a nineteen year low at the height of the market panic in March, before erasing the majority of its losses amid an aggressive stimulus injection from the Peruvian government. Since mid-June PEN has, however, begun to sell-off again, an idiosyncratic move that we think has been triggered largely by the aggressive spread of the virus in the country. This ensures that the currency is now trading appropriately 6% lower since the turn of the year (Figure 13). In relative terms, the currency continues to remain the least volatile in Latin America, largely due to ongoing intervention from the Central Reserve Bank of Peru.

Figure 13: USD/PEN (July ‘19 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

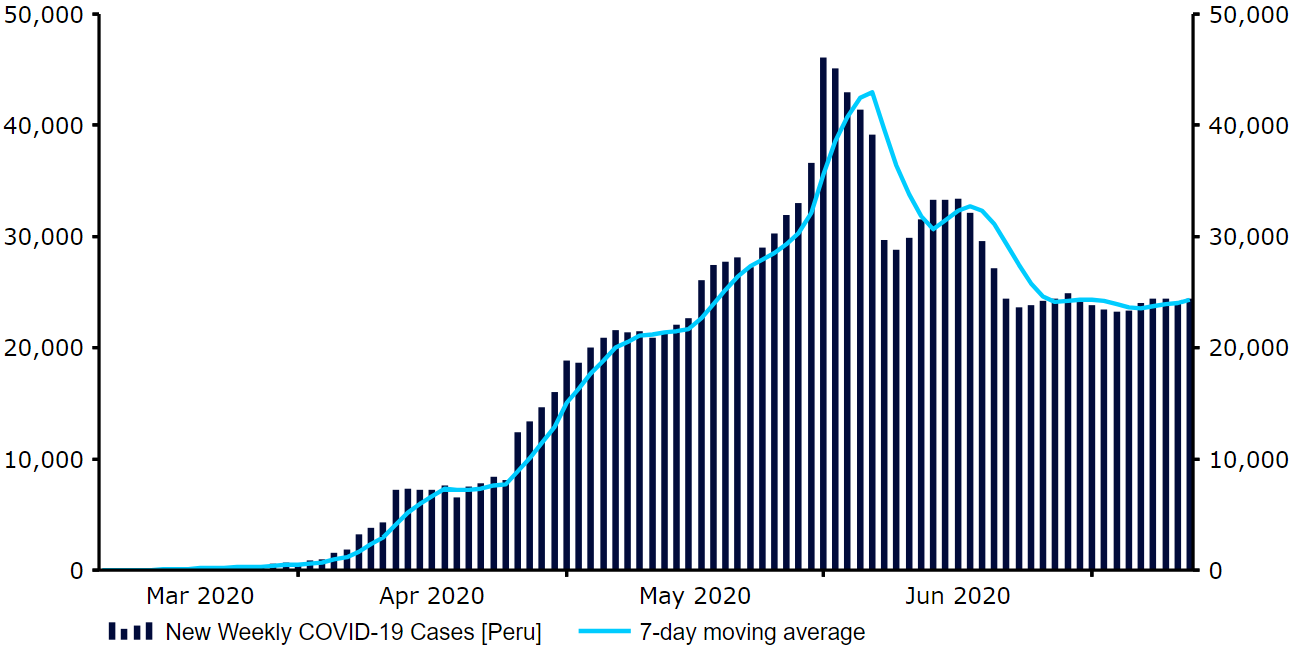

Peru has been one of the worst affected countries in the world by the pandemic, so far reporting more than 325,000 cases at the time of writing – among the highest in the world in terms of cases per capita. While the number of official new cases appear to have stabilised (Figure 14), the number of deaths caused by the virus has continued to increase. An inadequate health system, including unequal access to health care and a shortage of medical supplies, has left some regions ill-equipped to deal with the pandemic. Corruption has also reportedly left many of the most vulnerable without financial assistance, causing large numbers to flaunt the strict lockdown measures. More than 500 inquiries have been opened up since the beginning of the national lockdown in March, with most looking into whether officials have embezzled funds designed to pay for aid or protective equipment.

Figure 14: New Weekly COVID-19 Cases [Peru] (March ‘20 – July ‘20)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

With low levels of government debt (27% of GDP) and a vast hoard of savings, the Peruvian government has been in the enviable position to be able to pump a huge amount of stimulus into the economy since the onset of the crisis.

Authorities in Peru have unveiled mammoth and wide-ranging stimulus programmes equivalent to almost 17% of the country’s GDP – the largest in the region. This includes spending on healthcare, cash handouts and targeted relief for those worst affected areas of the economy, such as tourism. While this has helped support local assets, the high levels of corruption at the municipal level ensures that efforts to provide financial aid to those that most need it have not been entirely successful.

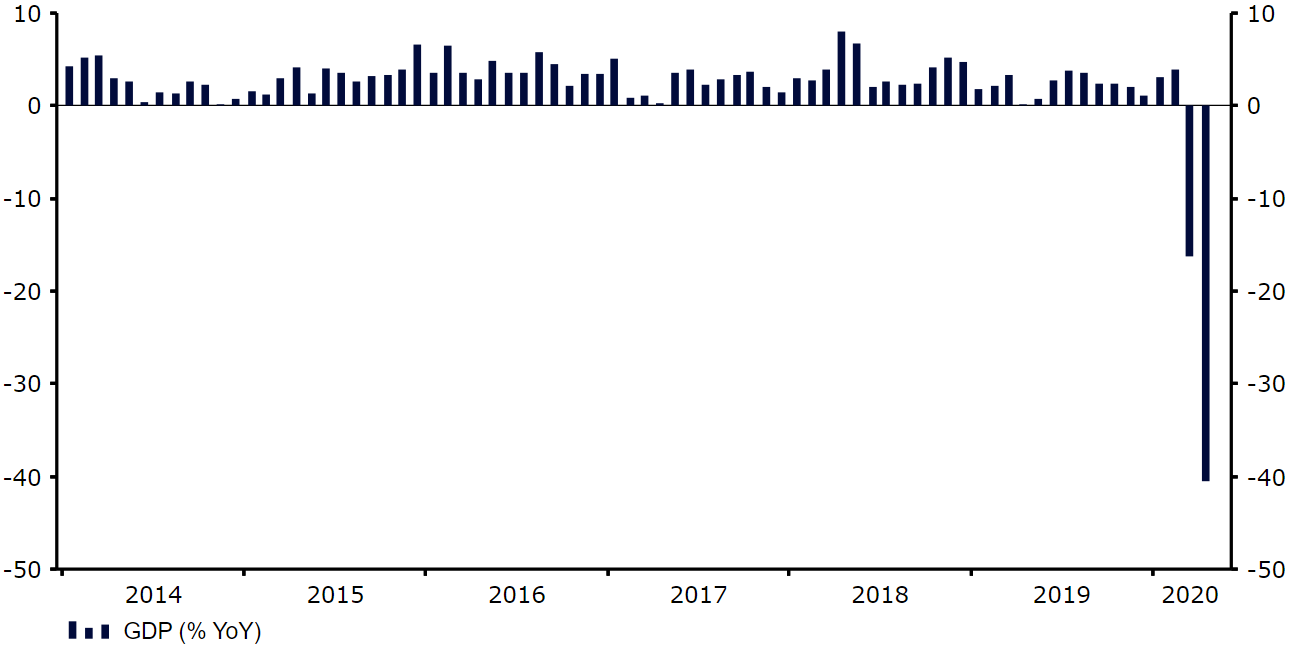

Amid the drastic measures to contain the spread of the virus, the impact on the Peruvian economy has been devastating, highlighting the need for the aforementioned stimulus. Peru’s GDP contracted by 40.5% year-on-year in April (Figure 15), its largest downturn on record. This was driven by complete collapses in the construction (-89.7%), manufacturing (-54.9%) and mining (-42.3%) sectors. Most economic indicators for May are not yet available, so we have so far seen no signs of a rebound in activity from these lows.

Figure 15: Peru Annual GDP Growth Rate (2014 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 14/07/2020

We remain optimistic over the new sol. The sell-off in PEN since June has created a rare divergence in the currency with that of global copper prices, to which the Peruvian economy is heavily linked. London Metal Exchange (LME) copper prices have continued to rise at a steady pace since tumbling to a more than four-year low in March and are now back above US$6,000 per tonne. Should this uptrend in copper prices continue, we think that we would likely begin to see this translated into a stronger new sol.

The Central Reserve Bank of Peru has also continued to intervene in the market in order to protect the currency, selling its FX reserves aggressively during the height of the turmoil in March and April. We think that it will continue to do so in the coming months, should sentiment towards PEN take a turn for the worse. With foreign exchange reserves still equating to around 35% of GDP, we think that the central bank should have plenty of room to continue intervening in order to limit currency fluctuations. Peru’s current account is also very manageable, with the deficit standing at just 1.5% of GDP last year. A combination of emigrant remittances and foreign direct investment should be sufficient to cover this deficit. The return of real interest rates back into negative territory for the first time since 2016 after 200 basis points of central bank cuts does, however, present a downside risk to the new sol.

Given the ample room available for continued central bank intervention and additional fiscal spending on top of the sizable measures already announced, we think that the new sol is well placed to rebound against the US dollar from current levels. We think the central bank should then have no problem in maintaining stability in the USD/PEN exchange rate around the 3.30 level over the longer-term.