Europe FX Forecast Revision – April 2021

( 12 min )

- Go back to blog home

- Latest

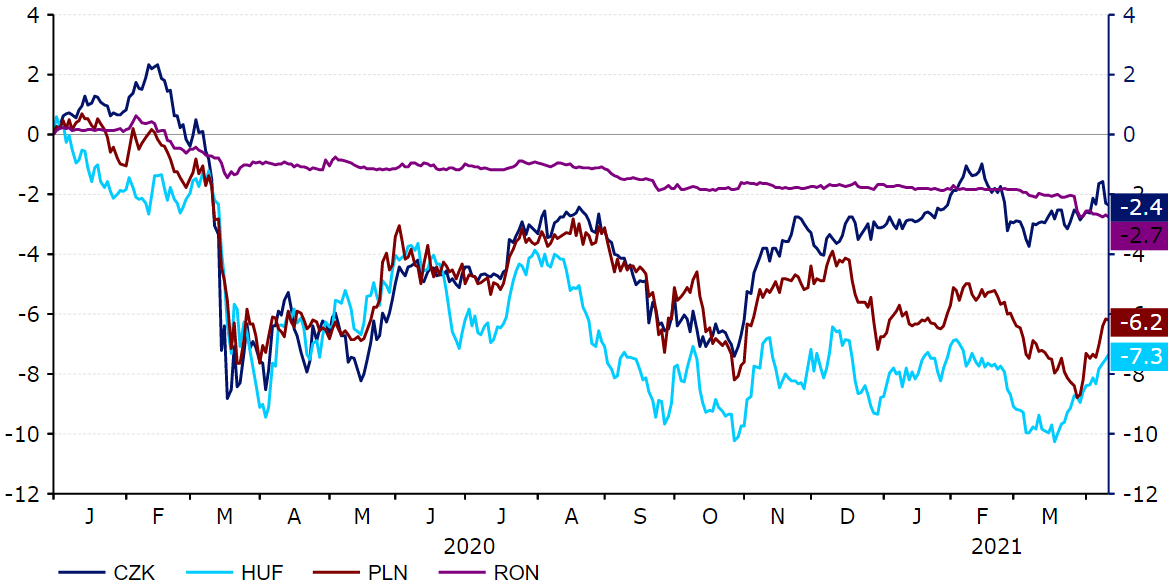

While the sell-off in Eastern European currencies was not quite as dramatic as other regions in 2020, the moves lower witnessed in the region was of a magnitude unseen in years.

Figure 1: CZK, HUF, PLN & RON [% change vs. euro] (April ‘20 – April ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

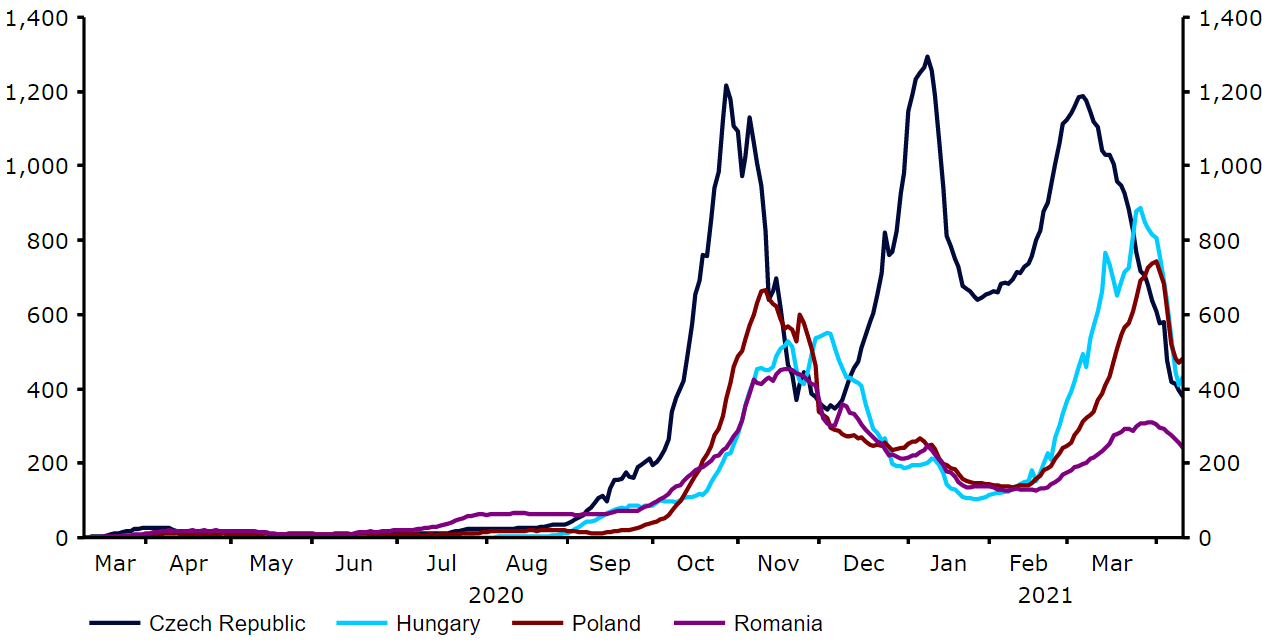

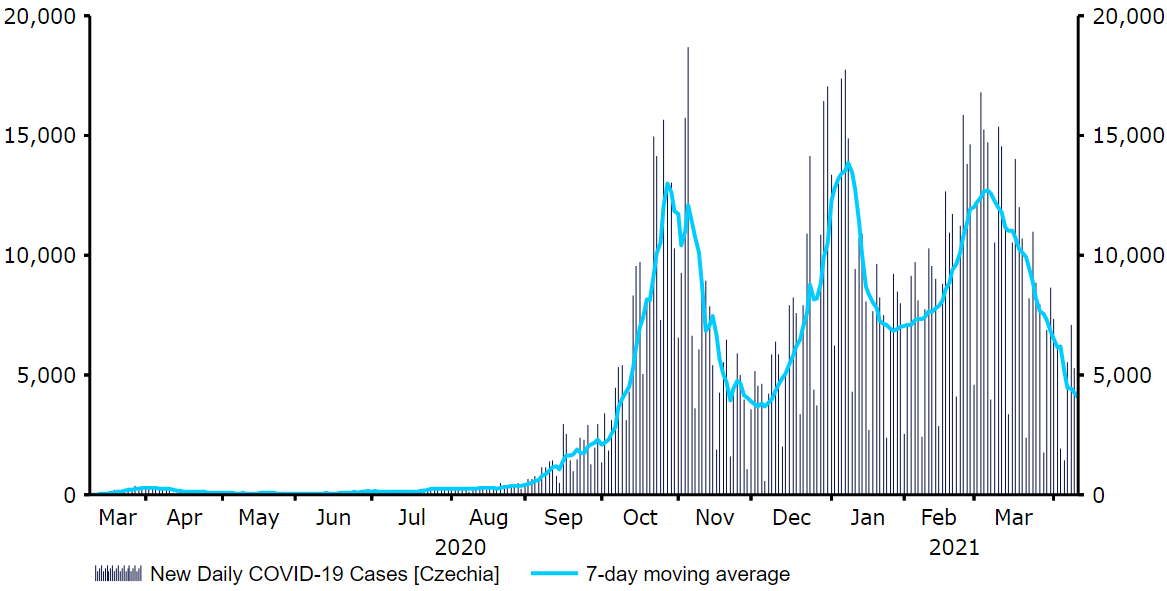

Since our latest European forecast revision in December, most of the currencies in the region have seen gains reversed, with both internal and external factors turning unfavourable. The pandemic situation has worsened in the region since late-February, partly a result of the emergence of faster-spreading strains of the virus. The most rapid increase in new cases took place in the Czech Republic, where the 7-day moving average of new cases reached a peak in early-March, just below the previous one set in early-January. In other countries covered in this report, this peak in caseloads has taken longer, although the worst of the third wave of infection in the region as a whole tentatively appears to be behind us.

Figure 2: New COVID-19 Cases [CEE] (March ‘20 – April ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

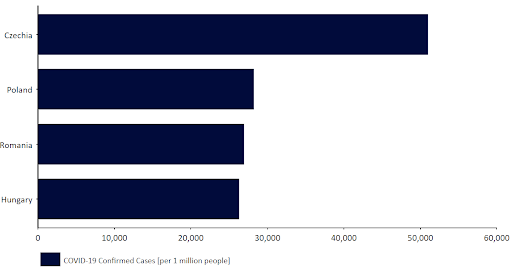

Of the four countries, Romania has so far experienced the lowest rate of infection per capita (around 51,000 per 1 million people) – partly a product of relatively limited testing. The Czech Republic has fared the worst (more than 145,000 per 1M) (Figure 2), although we note that the 7-day average of Poland’s test positive rate, which represents the number of confirmed virus cases per 100 tests, is now at around 30%. This continues to outstrip the other three nations throughout the third wave of the virus. That being said, Poland’s COVID-19 death rate per 1 million people remains the second-lowest (1,473) after Romania (1,283), with the Czech Republic having the highest (2,548)*.

Figure 3: COVID-19 Confirmed Cases and Deaths [per 1M people] [CEE] (as of 13/04)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

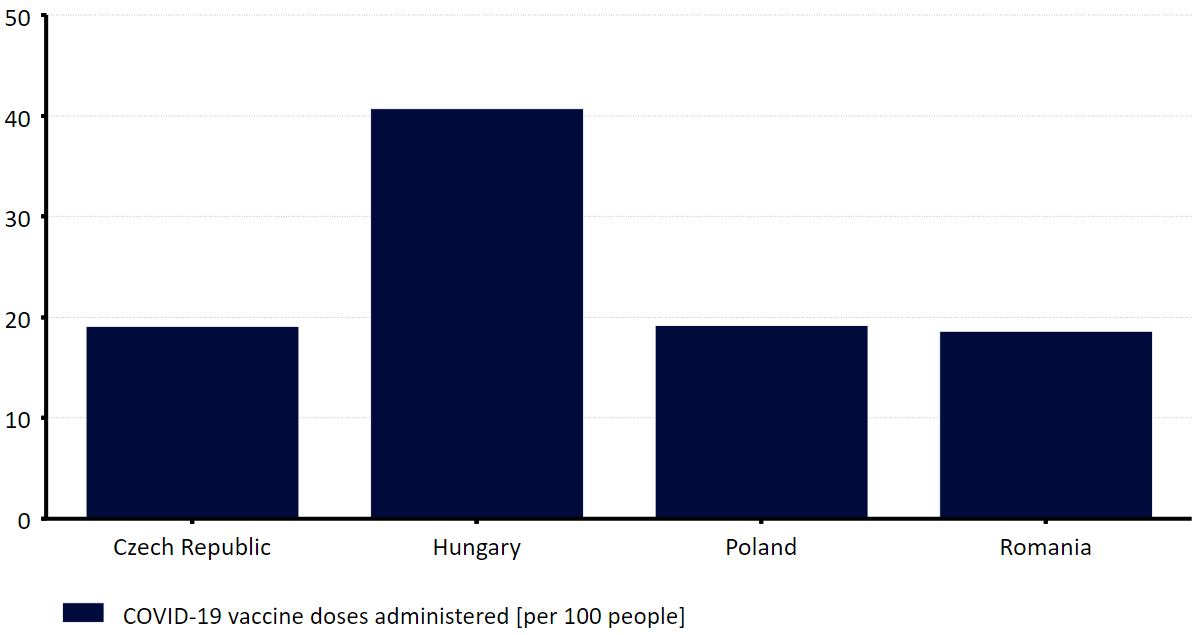

As has been the case in other EU countries, vaccine progress in the CEE region has been rather slow. Most of them have distributed around 17 doses of the vaccine per 100 people at the time of writing. The outlier, Hungary, has distributed around 37 doses of vaccine per 100 people so far using the Russian (Sputnik V) and Chinese (Sinpoharm) vaccines. The pace of vaccinations eased somewhat in the EU and most CEE countries on two occasions: in mid-March (which we attribute to concerns regarding possible side effects of the AstraZeneca vaccine) and in early-April (which we attribute to the Easter holidays). Inoculations are, however, expected to accelerate in the next few months. Based on the available information, we expect the pace of vaccinations to increase notably in the region in the second and third quarters of 2021.

Figure 4: COVID-19 vaccine doses administered [CEE] [per 100 people] (as of 13/04)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

In addition to the resurgence of the virus in the region, the CEE currencies have been hurt by externalities, in particular rising US bond yields, a weaker euro and a strengthening of the US dollar. While sentiment towards Eastern European currencies has remained far from positive in the past few months, we are confident that the majority of them have the potential to reverse most, if not all, of their losses over our forecast horizon. Acknowledging the unfavourable present situation we have pushed our expectations regarding an appreciation of the Polish zloty and the Hungarian forint forward. We continue to believe that the zloty and Czech koruna will emerge as the region’s best performers in 2021. On the other side of the spectrum lies the Romanian leu, for which we predict a continued, albeit limited, downtrend. Much of this will, of course, depend on how well each economy bounces back once virus restrictions are lifted.

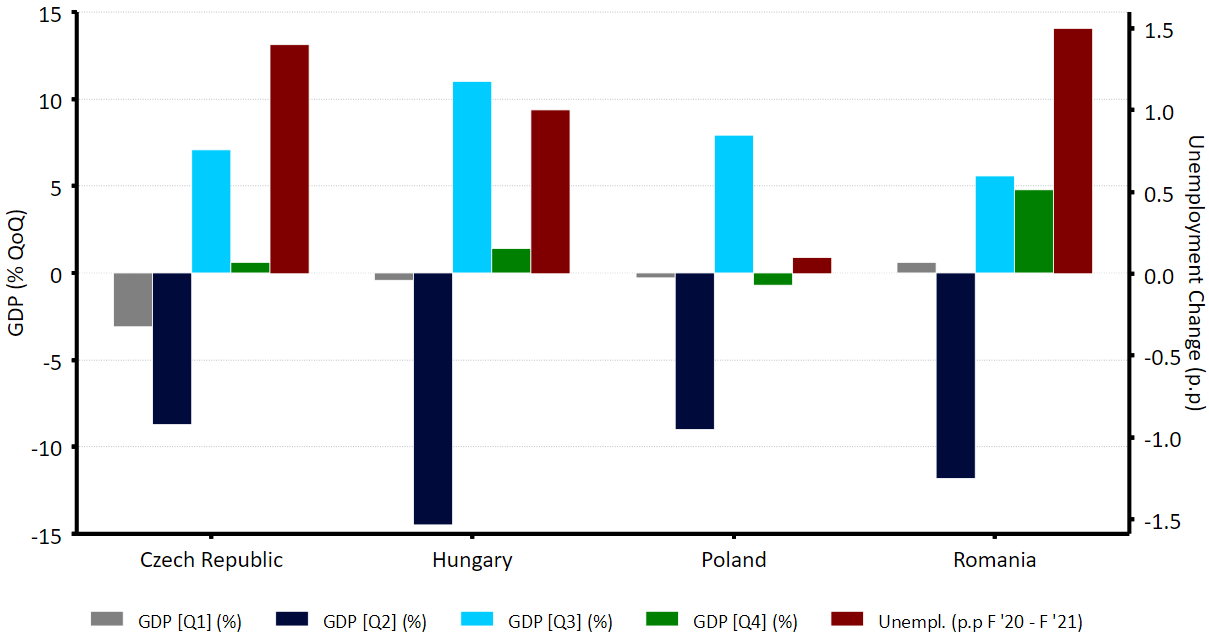

So far, the strict measures put in place to limit the spread of the virus have led to sharp deteriorations in the region’s economies. In each of the countries mentioned in this report, the yearly decline in 2020 was of a more limited extent than in the Eurozone or the EU as a whole. Of the bunch, the Czech Republic has experienced the worst downturn, while Poland the smallest. Labour market data also tells a similar story, with all four nations suffering from a shallower increase in joblessness than most EU nations since the beginning of the crisis. The best indicator for cross-country comparison, the seasonally-adjusted ILO unemployment rate, increased by +0.1 p.p. in Poland (to 3.1%), +1 p.p. in Hungary (4.5%), +1.4 p.p. in Czech Republic (3.2%) and +1.5 p.p. in Romania (5.7%) between February 2020 and February 2021 (Figure 4).

Figure 5: CEE Macroeconomic Performance [during COVID-19 pandemic]

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

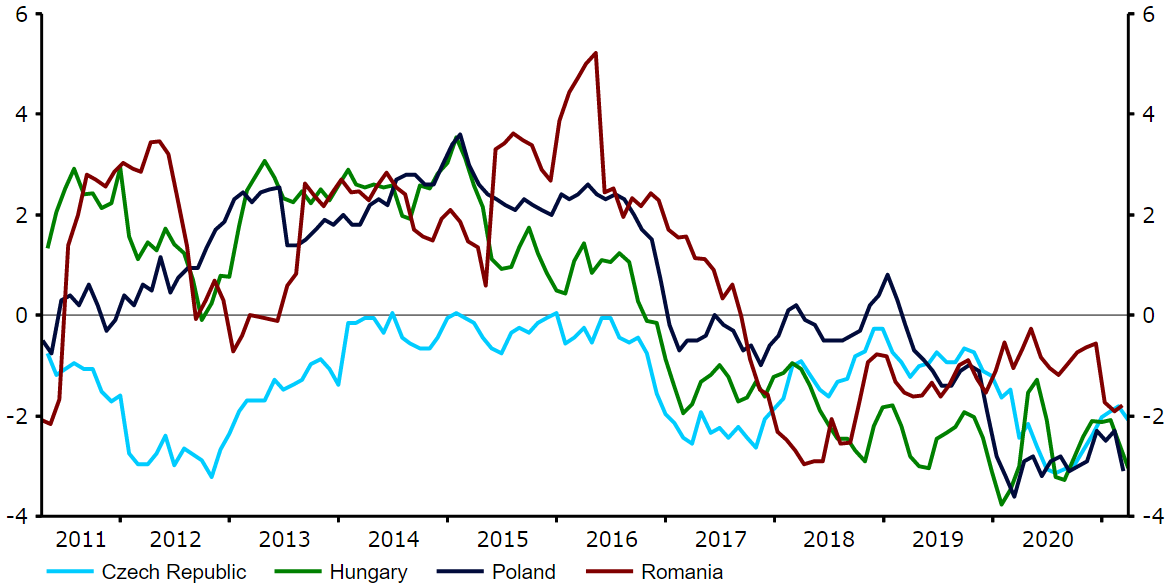

We believe that these four currencies have an advantage over non-European emerging market currencies due to the simple fact that the respective countries lie in Europe and are all members of the European Union. This, in our view, has led to a decrease in perceived risk of them as a group among investors. In addition, most of them have very sound macroeconomic fundamentals, comparable to more developed nations, carry limited political risk premiums and are not commodity-dependent. This leads to typically lower volatility than seen among many of their emerging market peers and supports our call regarding their rebound. A potential issue for these currencies is that real interest rates in the region are now all firmly in negative territory (Figure 6), which does present a bit of a downside risk.

Figure 6: CEE Real Interest Rates (2011 – 2021)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

*COVID-19 cases and deaths statistics used in this report come from Worldometer (Worldometers.info), as of 13/04/21

**COVID-19 testing and inoculation rates used in this report come from Our World in Data (ourworldindata.org), as of 13/04/21

Czech Republic Koruna (CZK)

The Czech Republic koruna fell by around 9% versus the euro year-to-date at one stage in March 2020, with pandemic fears sending the currency to its lowest level since early-2015.

Since then, the currency has managed to regain around half of its losses, although it sold-off again near the end of the summer as the second wave swept through Europe, hitting the Czech Republic particularly hard. As cases began to ease, the currency managed to rally and continued on its upward path even as the pandemic situation in Czechia worsened again in late-December. The koruna finally crumbled under the pressure in late-February, with rising caseloads and higher US bond yields pushed the EUR/CZK pair higher. At the time of writing, the koruna is currently trading around the 25.8 level versus the euro (Figure 7), having regained most of its losses on improving domestic virus news and an uptick in sentiment towards EM currencies.

Figure 7: EUR/CZK (2020 – 2021)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

The third wave of the virus has hit the Czech Republic particularly hard. The country has reported around 1.6 million cases since the beginning of the crisis (more than 147,000 per 1 million people) and 28,000 deaths (2,614 per 1M). Around two-thirds of these deaths have been reported since our last update in December. The situation is now improving, with Czechia one of a handful of countries in the region to post declines in both new cases and deaths. Due to increased testing the country’s test positive rate has dropped to around 3% of the time of writing – by far the lowest of the four countries in this report.

Figure 8: Czech Republic New COVID-19 Cases (March ‘20 – April ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

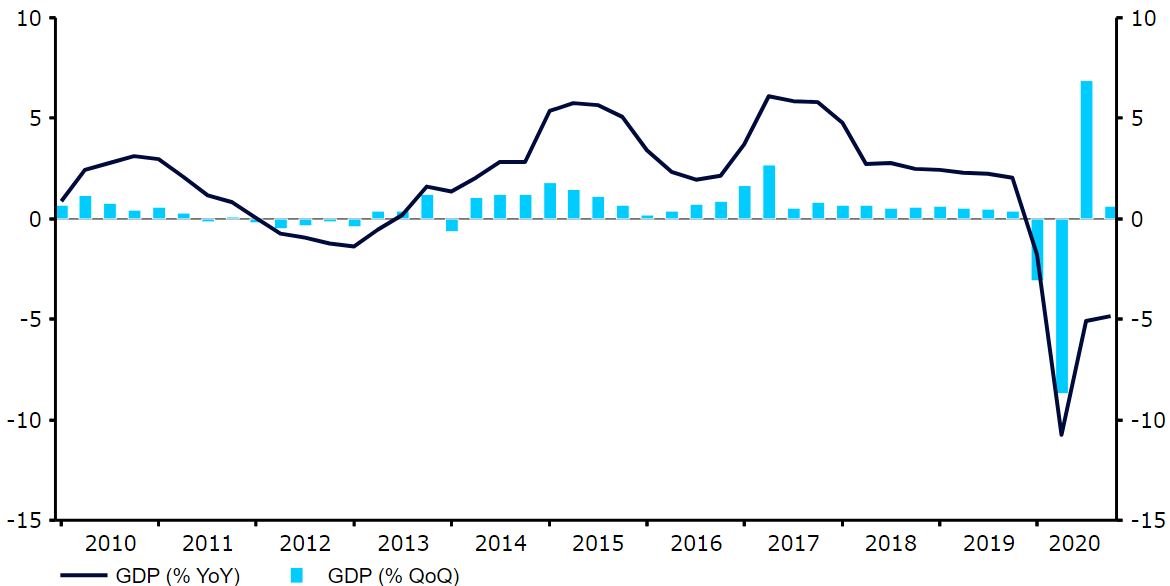

The Czech government acted early during the first wave of infection and was one of the first EU countries to close its borders, introduce a nationwide quarantine and the mandatory wearing of face masks. While this helped limit the spread of the virus in the spring of 2020, it took a toll on the country’s economy. Manufacturing, which plays a larger role in the Czech Republic than in the EU and in the other three CEE economies analysed in this report, was hit particularly hard. GDP fell by 1.8% year-on-year in the first quarter of last year and dropped by an eye-watering 10.8% in the following one.

The decline in the first quarter was driven largely by changes in gross capital formation (namely a drop in investments), while in the second quarter the slowdown was due to a decline in net exports, consumption and gross capital formation. Activity picked up in the second half of 2020, although GDP still declined by 5.1% year-on-year in the third quarter and by 4.8% in the fourth. The decline in that period was driven by changes in gross capital formation and to a lesser extent consumption, with trade contributing positively to overall growth.

Figure 9: Czech Republic Annual GDP Growth Rate (2010 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

The high importance of trade to the country (exports accounted for 75.5% of overall GDP in 2019) is a challenge given the ongoing pandemic. Recent data has, however, provided hope that exports could be one of the key engines for the country’s economic rebound. While the industrial sector is continuing to face difficulties, the improvements witnessed in business activity data provide reason to be hopeful – the manufacturing PMI surged to 58 in March, its highest level in more than three years.

With one of the lowest public debt levels in Europe, the Czech Republic has been able to use its fiscal space to support the economy. The government announced a fiscal package worth around 18% of the country’s GDP in mid-March last year, which was then expanded in the following months. The vast majority of this does, however, come in a form of loan guarantees and other indirect measures. One of the key elements of the package, the Antivirus Programme, has helped shelter jobs and was recently extended again to support employment through to the end of April 2021. As expected, the country also approved a large tax plan worth around 100 billion CZK (close to 1.5% of GDP) near the end of the year. This should ease the burden on employees and further support the economy both this year and next. In addition, the Czech Republic can count on further support from the EU as a beneficiary of the €750 billion recovery fund launching this year on top of a variety of measures introduced earlier in 2020.

In response to the crisis, the Czech National Bank (CNB) eased monetary policy by cutting interest rates by a total of 200 basis points between March and May last year, while also introducing other supplementary measures. In contrast to the other three CEE countries in this report the bank didn’t introduce an asset-purchase programme. During its last meeting in March, the central bank kept interest rates unchanged. Given the downside risks associated with the third wave of the virus both in Czechia and other countries in Europe, it is unlikely that the bank will rush into tightening monetary policy, although we think that the CNB will most likely hike rates before the end of the year. Our expectation is supported by the CNB’s own forecast for 3M PRIBOR, which indicates 3-4 hikes in 2021.

Nonetheless, the pace of tightening implied by the forecast appears to be too fast and the CNB Board continues to distance themselves from it by noting that it “assessed the uncertainties and risks of the forecast in the context of the ongoing pandemic as remaining very substantial. This could lead to a need to keep the monetary conditions accommodative for rather longer than in the forecast.”

We continue to believe that the Czech koruna may be one of the best-performing CEE currencies in the coming quarters. While the Czech economy has been battered by the pandemic we think that it has every reason to recover in 2021, particularly given the government’s accommodative fiscal policy. The third wave of the virus presents a challenge, although we’re encouraged by recent improvements on that front. The Czech Koruna also has one of the best, if not the best, fundamentals in the region, including a positive current account and fiscal environment which, in our view, should also help the currency recover versus the euro.

While we find it hard to believe that the CNB will be able to tighten monetary policy to the extent indicated in its February forecasts, we think a hike in the second half of 2021 is more likely than not and believe that the Czech Republic will be the first among the countries in this report to begin policy normalisation. This should further support the koruna during our forecast horizon. We are, therefore, keeping our EUR/CZK forecast unchanged from December.

Hungarian Forint (HUF)

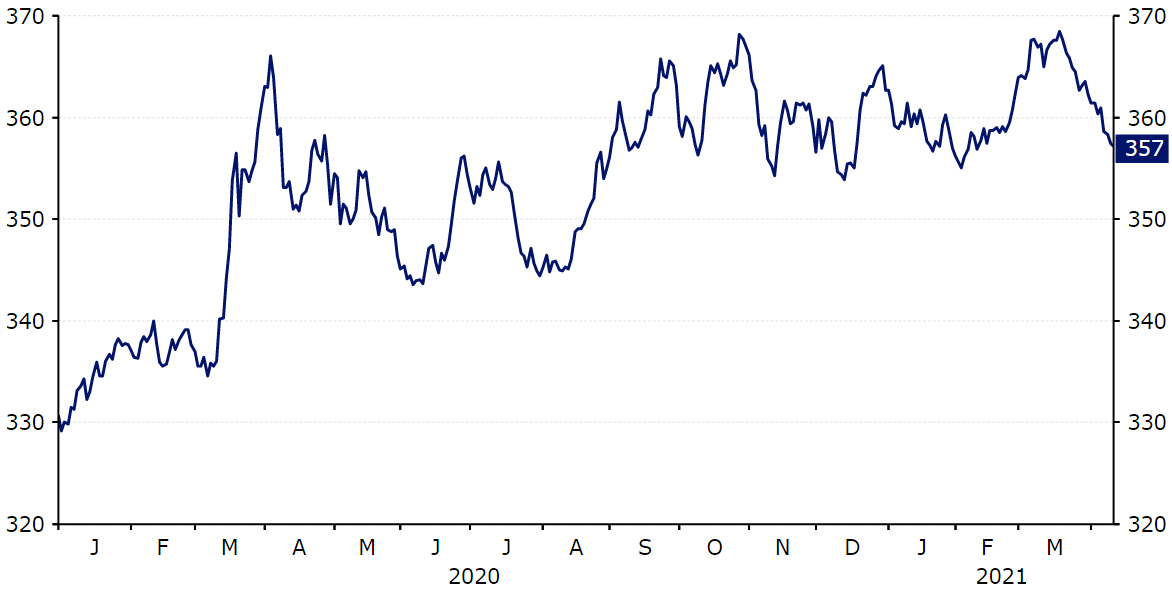

In the months between the beginning of the year to its lowest level during the height of the market panic in late-March 2020, the Hungarian forint sold-off by more than 10% versus the euro.

This depreciation left the forint at its weakest ever level, just below 370 to the euro. Since then it has been quite volatile, enjoying periods of appreciation followed by declines. As a result of risk-off sentiment and a worsening in the pandemic situation, the currency has sold-off again since late-February. In the past few weeks the currency has, however, managed to regain those losses (Figure 10).

Figure 10: EUR/HUF (2020 – 2021)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

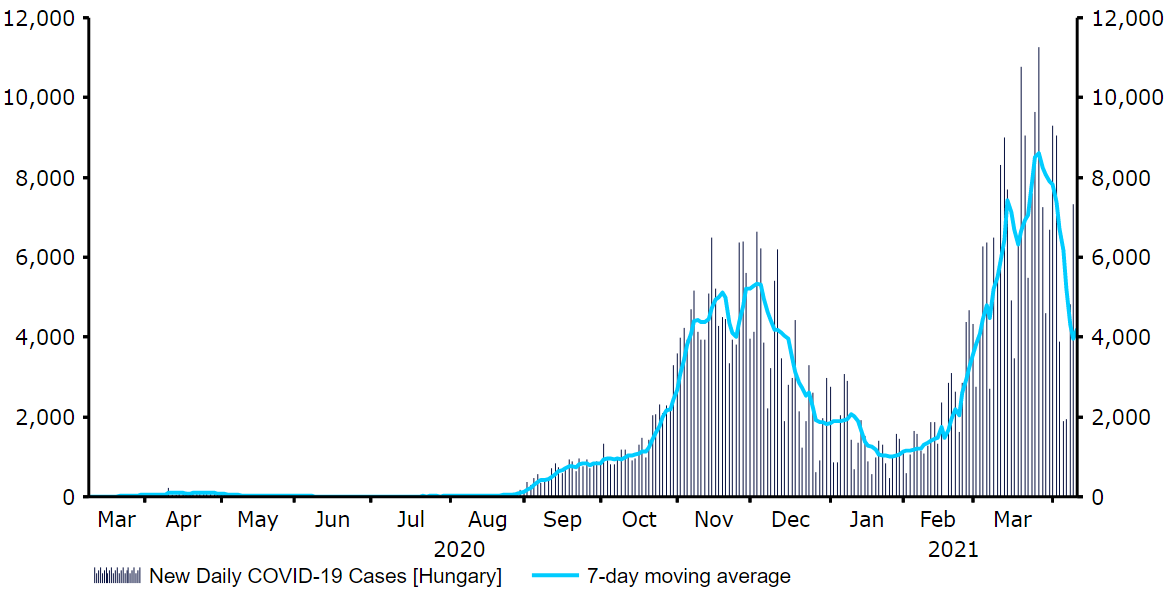

The situation in Hungary has deteriorated since our last revision in December. The country has gone from registering the lowest number of confirmed COVID cases and second-lowest number of deaths of those in this report to the second-worst affected according to those metrics (72,000 and 2,324 per 1 million people respectively).

As has been the case elsewhere in the region, the third wave of the pandemic has proved to be much worst than the first two. The 7-day moving average of new cases rose to 9,500 in late-March, compared to the previous peak at around 5,800 in early-December. While some of the increase has to do with greater levels of testing, this explains only some of the spike in cases. Additionally, new deaths have reached new highs – the 7-day average recently crossing the 250 level for the first time. This led to a tightening of restrictions in early-March for the first time since November last year, including the closure of non-essential businesses. Hungary’s COVID-19 Government Response Stringency index, courtesy of Oxford University, rose to 79.6, its highest level since the onset of the pandemic. Limits on gatherings remain in place, as does the night curfew introduced during the second wave.

Figure 11: Hungary New COVID-19 Cases (March ‘20 – April ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

We have little doubt that the vulnerability shown by the currency during the pandemic period is a product of Hungary’s relatively weaker economic fundamentals. These fundamentals are mostly solid relative to the broad emerging market spectrum, although stand out in a negative way compared to most of its regional peers. Unlike the other three countries in this report, Hungary’s debt-to-GDP ratio was above the EU’s 60% threshold prior to the pandemic, despite improvements in public finances in recent years that have been helped by robust economic growth and low fiscal deficits. Hungary also has the highest level of external debt of the four – above 90% of GDP in 2019.

The country’s creditworthiness is perceived to be the second-worst in the group, after Romania, according to credit ratings and CDS prices. Prior to the pandemic, the country’s monetary policy stance was also looser than its peers, despite stubbornly high inflation. Hungary’s foreign exchange reserves are also relatively scarce and cover the equivalent of only four months of import cover – among the lowest of all the emerging market countries that we cover.

Hungary’s government announced relatively harsh restrictions at the onset of the pandemic, which have limited economic activity in the country since March. This was reflected in the national accounts data. In the first quarter, GDP growth declined to 2.3% year-on-year, around half of its pre-COVID levels. In the second quarter, which saw the greatest period of restrictions, the economy contracted by an eye-popping 13.4%. This record contraction was followed by a much smaller annual decline in the third quarter as activity bounced back from the downturn earlier in the year, with GDP falling by 4.6% from the previous year. As expected, the fourth quarter brought a continued downturn, but at 3.6% it was much more limited than in the second quarter.

In an attempt to support the economy, Hungary’s government has introduced a set of measures which, combined with those from the central bank, are worth approximately 20% of the country’s GDP. These include tax cuts, direct subsidies and a set of indirect measures. Similarly to other European countries, including its peers in the CEE region, the government appears to be placing heavy emphasis on stabilising the labour market from the shock triggered by the pandemic. As in other member countries in the region, Hungary can count on further support from the European Union, particularly in the form of the EU’s €750 billion recovery fund mentioned earlier kicking-off this year.

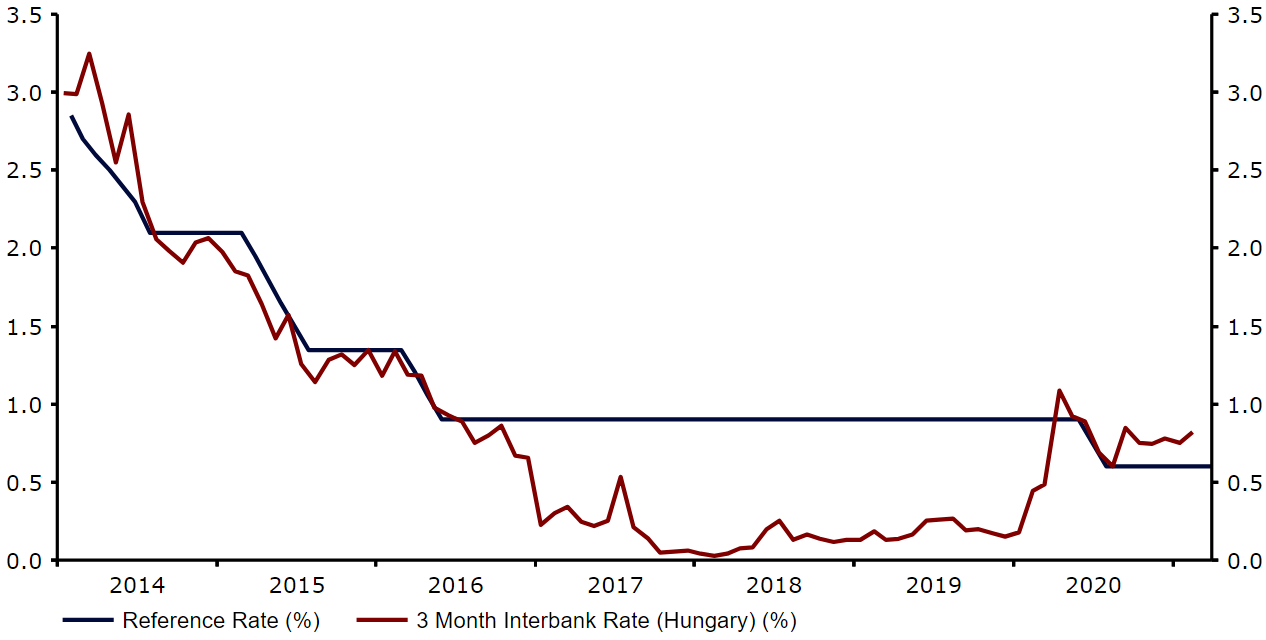

While its main goal is ensuring price stability, the National Bank of Hungary (MNB) has had little choice but to keep a special focus on alleviating the negative impact of the pandemic. Contrary to its regional peers, with the exception of verbal intervention from the CNB, the MNB has acted to support the domestic currency from further depreciation. The forint has been helped by modifications to a number of non-base interest rates and more recently, by more hawkish rhetoric from the MNB. To support the economy, the bank has focused mostly on alternative measures (including different QE and financing programmes). It also lowered its reference rate by a total of 30 basis points to 0.6% between June and July. Nonetheless, it’s important to note that the interbank BUBOR rate remains significantly higher than at the beginning of 2020 (Figure 12), in contrast to interbank rates of the three other countries, which have declined sharply, pushed down by sizable interest rate cuts.

Figure 12: Hungary Interest Rates (2014 – 2021)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

Hard lockdown measures that have recently been tightened due to another wave of the virus suggests that a serious economic rebound will likely be pushed further into the future. Fast vaccination progress and a series of fiscal and monetary measures introduced in order to support the economy do, however, make us hopeful that the country is well-positioned for a rebound in activity after the third wave passes.

That being said, the country’s relatively weak macroeconomic fundamentals compared to most of its peers mean that we think the forint, contrary to the Polish zloty and Czech koruna is unlikely to reach its pre-pandemic levels within our forecast horizon. Acknowledging the unexpectedly harsh third wave of the pandemic in the country and unfavourable external developments, we have revised our short-term forecast for EUR/HUF.

Polish Zloty (PLN)

Soon after our latest regional update in December, the National Bank of Poland unexpectedly conducted a series of FX interventions aimed at weakening the zloty.

Since then, the zloty has recovered some of these losses, although weakened again following the surge in virus cases in the country’s third wave of infection and a worsening investor appetite for risk. At the time of writing, the currency is rebounding again, as the third wave starts to fade and global sentiment improves (Figure 13).

Figure 13: EUR/PLN (2020 – 2021)

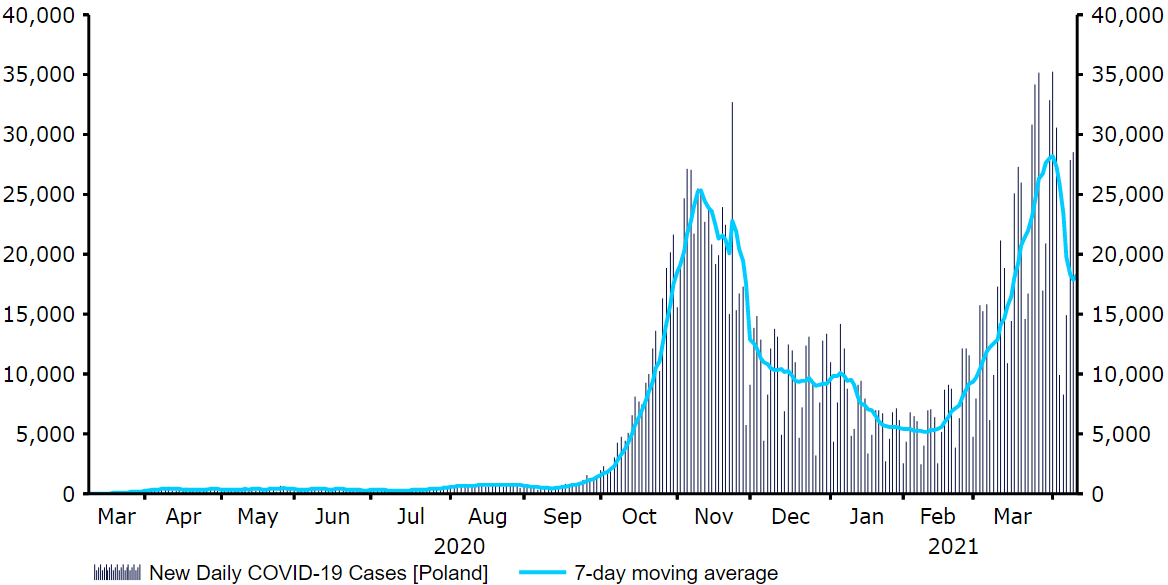

As has been the case elsewhere in the region, the third wave of COVID-19 virus has been significant in Poland. So far, nearly 2.5 million cases of the virus have been confirmed (around 65,000 cases per 1 million people), with more than 55,000 deaths (nearly 1,500 per 1M). Following the outbreak of the virus in early-2020, the Polish government was quick to act – the restrictions put in place were introduced relatively early and were among the harshest in the continent. The second and third waves were much worse than the first one in Poland, leading to a gradual return of many of these restrictions, with the most severe ones reintroduced in October last year and further tightened in March. The key measures currently in place include the closure of restaurants, bars, gyms, and schools, limitations regarding retail stores and non-essential businesses and mandatory mask-wearing in public.

Figure 14: Poland New COVID-19 Cases (March ‘20 – April ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

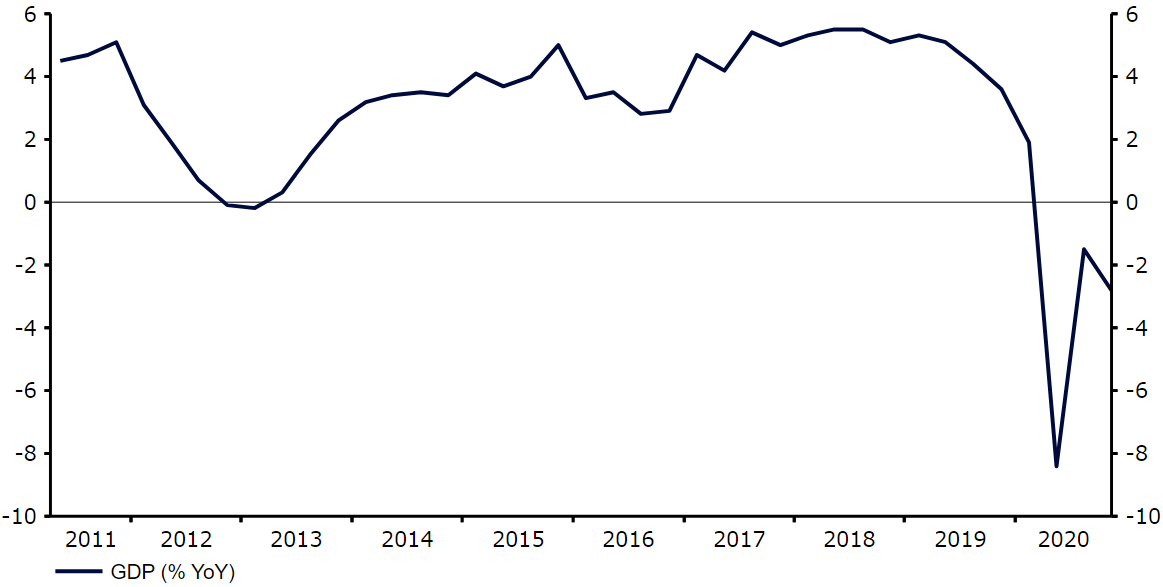

The blow to the Polish economy from the introduction of restrictions designed to halt the spread of the virus resulted in the first annual GDP contraction in Poland since 1991 last year. In the first quarter of 2020, GDP rose by only 1.9% year-over-year – around half its long-term average, with activity declining by 8.4% in the second quarter. Most of this downturn came as a result of a sharp contraction in domestic consumption. Interestingly enough, next to government spending, trade contributed positively to second-quarter GDP. This resilience is one of the most promising signs in the current environment. The economic situation improved noticeably in the third quarter. Despite relatively robust levels of consumer spending, the Polish economy contracted once again, by 1.5% year-on-year. As many restrictions were brought back, the fourth-quarter brought yet another decline of 2.8% year-on-year driven by a decline in investments and consumer demand (Figure 15). Looking at the data for the entire year, regardless of whether we compare the scale of the decline or the difference between the long-term trend and the decline in GDP, Poland still comes out as one of the best-performing economies in the EU. This can be linked with a number of factors, primarily a favourable economic structure in the context of such a shock (including a small share of tourism in the country’s GDP) and significant state support.

Figure 15: Poland Annual GDP Growth Rate (2015 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

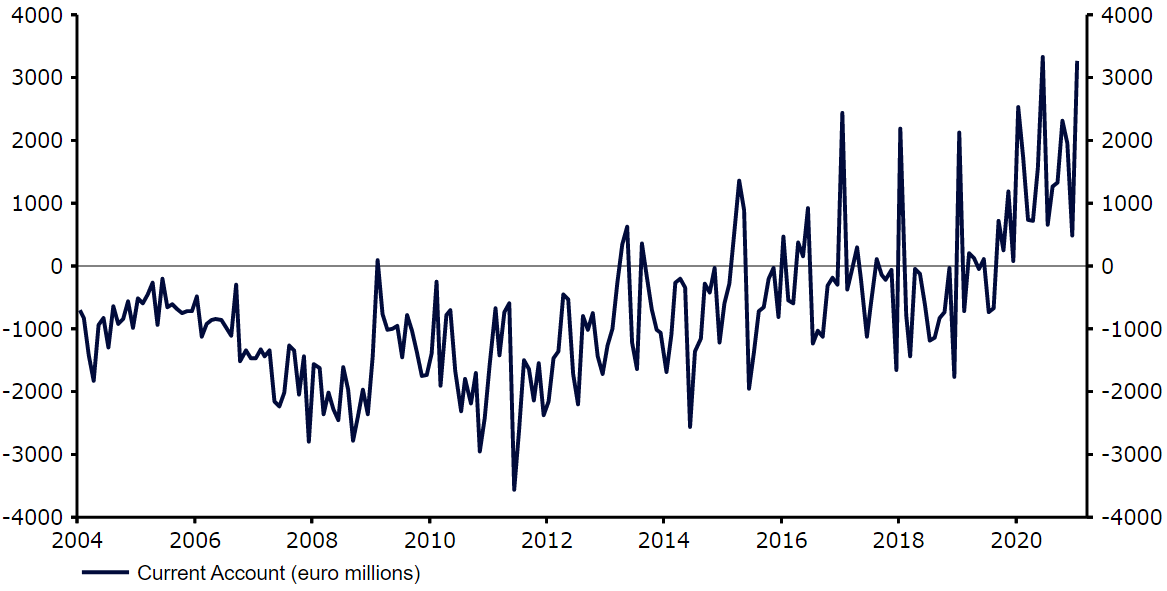

Positive net export growth has also translated into an improvement in the country’s current account. By our calculations, Poland recorded its highest current account surplus as a percentage of GDP since the 1990s at 3.5% in 2020 and the second-highest in the country’s modern history (Figure 16). This, in our view, is a clear positive development for the Polish zloty.

Figure 16: Poland Current Account Balance as % of GDP (1990 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

Despite the severity of both the second and third waves and the harsh restrictions currently in place, Poland’s economic prospects after the passing of the third wave in the weeks to come appear positive. A significant resilience in the country’s labour market should help support economic activity in the coming months. The jobless rate has only increased relatively modestly since the beginning of the crisis, remaining stable at 6.1% in each of the five months through to October – only 0.6 p.p higher than before the start of the pandemic. This metric increased to 6.5% in January and February, but such an increase is normal for the winter period.

A number of indicators suggest that the industrial sector has gathered pace. The manufacturing PMI has remained above the level 50 in each of the past nine months, reaching its highest level since January 2018 in March. Industrial production has also been in positive territory year-on-year since June, and has increased at the beginning of the year in month-on-month terms. Similarly to the situation in the rest of Europe, concerns lie not with the resilient manufacturing sector, but with the performance of the services industry, which has been further harmed by the new restrictions.

Given the resilience in economic data and the fact that the current containment measures are less severe than those imposed in the spring, we are hopeful that the country’s economy will not suffer a blow of a similar magnitude as it did during the first wave. Since the start of the pandemic, the economic recovery has been supported by both fiscal and monetary policy. During the first wave, Poland’s government unveiled a stimulus package totalling an estimated 312 billion PLN – around 15% of GDP. Since then, the country has introduced a series of additional smaller-scale measures, with a 35 billion PLN package announced in late-November. The additional support is expected to be launched in the near future to help ease the burden of the most recent wave. While not all of the support was direct spending, Poland has unveiled one of the largest sets of fiscal measures within the EU relative to the size of the economy. Furthermore, Poland will be one of the biggest beneficiaries of the EU’s €750 billion recovery fund, which kicks off this year.

In response to the crisis, the National Bank of Poland slashed interest rates between March and May of 2020, cutting its reference rate by 140 basis points to 0.1%. It also announced the introduction of its own asset-purchase programme in April last year. The programme was initially comprised of merely government bond purchases, but this has been subsequently expanded to include treasury bills and government-backed bonds. The scale of the asset-purchase programme is significant. The NBP has already amassed more than 100 billion PLN of the country’s public debt, which has contributed to a significant expansion of its balance sheet.

The end of December brought a series of unexpected actions by the National Bank of Poland, which intervened several times in the currency market to weaken the national currency. Those actions were supported by the bank’s communication, which led to the market pricing in the possibility of further FX intervention and a lowering of interest rates in the first quarter of 2021. In our view, the key reason for these interventions was a desire to support public finances – most of the NBP’s profit supports the country’s budget, with a weaker zloty at year-end leading to a larger profit. We base our view on the timing of the interventions and the fact that Poland’s exports are doing exceptionally well and do not seem to be in need of support.

We believe that the NBP’s appetite for further intervention has decreased markedly for the below reasons:

1) We have not seen any currency interventions from the NBP since December.

2) Historical data suggests that the Polish economy has grown more resilient to the negative effects of the pandemic, and the outlook remains favourable despite the third wave.

3) Interest rates have been kept stable so far in 2021 and the NBP’s recent communications suggest that a cut is unlikely.

We think that the NBP will not undertake any serious currency interventions nor other significant actions even if the zloty were to strengthen from current levels in line with our forecast. We don’t think that the central bank will lower interest rates any further, even in the face of the third wave, nor do we pencil in a hike in 2021.

We revised our EUR/PLN forecast higher in early-February following FX intervention from the NBP and its impact on the market. Following the fierce resurgence of the virus in Poland and unfavourable external developments, we are revising our short-term forecast upwards again. We do, however, continue to believe that the zloty should return to levels more in line with the strong fundamentals of the country’s economy in the long-run. We remain very optimistic about the Polish currency and are encouraged by recent developments.

Romanian Leu (RON)

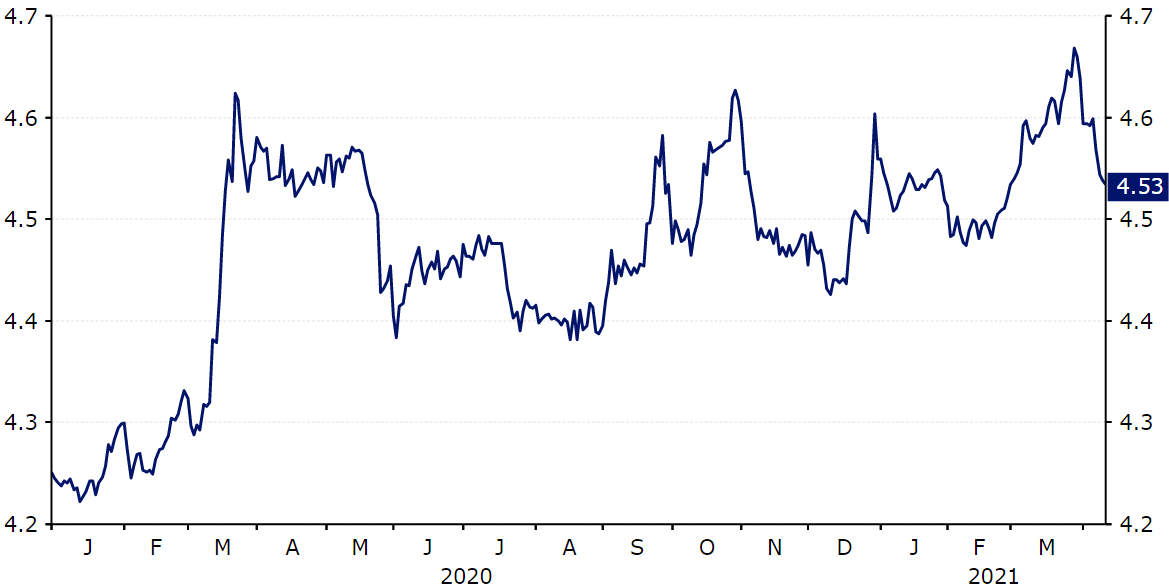

The Romanian leu (RON) lost around 2% of its value versus the euro in 2020. The pair has remained remarkably stable since late-September, which led us to revising our EUR/RON forecast in early-February to show more limited depreciation than previously expected (Figure 16).

In percentage terms, the leu’s decline in 2020 was rather limited, although this is a rather notable shift for a currency that is ordinarily largely stable versus the euro. The sell-off came amid a broad sell-off in risky assets induced by the pandemic, which led to mass moves lower in almost every emerging market currency. Despite relatively poor fundamentals, the scale of the leu’s decline was much more limited than those of its regional peers. We attribute this mainly to the fact that Romania’s currency is much more closely controlled by the central bank than its regional counterparts – the leu is typically one of the least volatile currencies globally.

Figure 17: EUR/RON (2020 – 2021)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

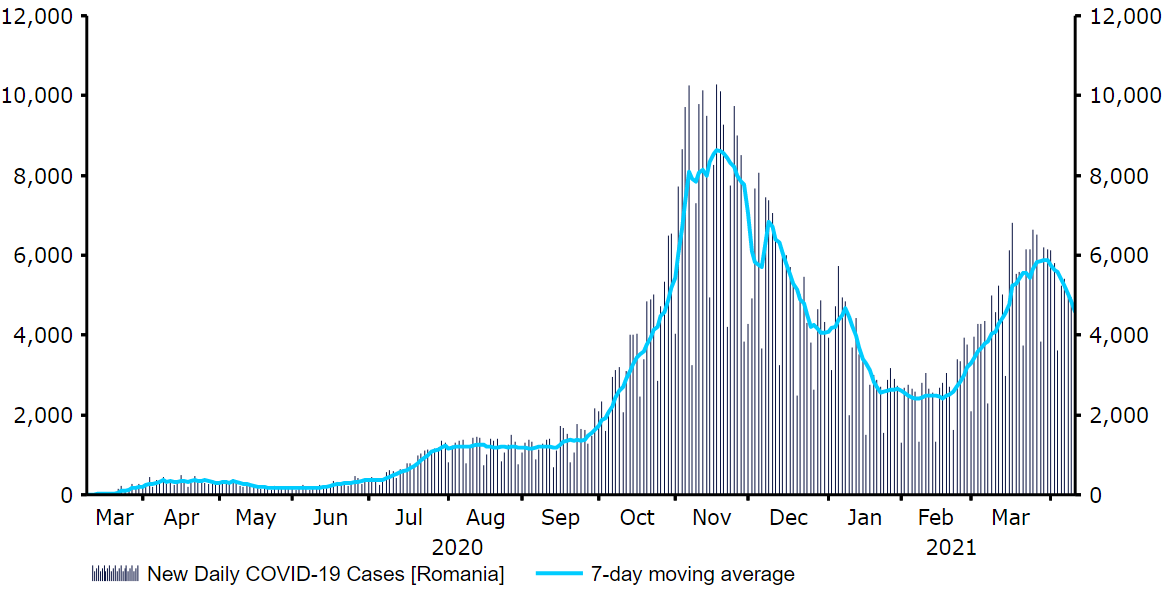

Both the second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic have led to a significant jump in both the number of new confirmed cases and deaths caused by the virus in Romania. Since the beginning of the pandemic, more than 988,000 cases (more than 51,500 per 1 million people) have been reported in the country, with approximately 24,500 COVID-19 related deaths (nearly 1,300 per 1M).

Figure 18: Romania New COVID-19 Cases (March ‘20 – April ‘21)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

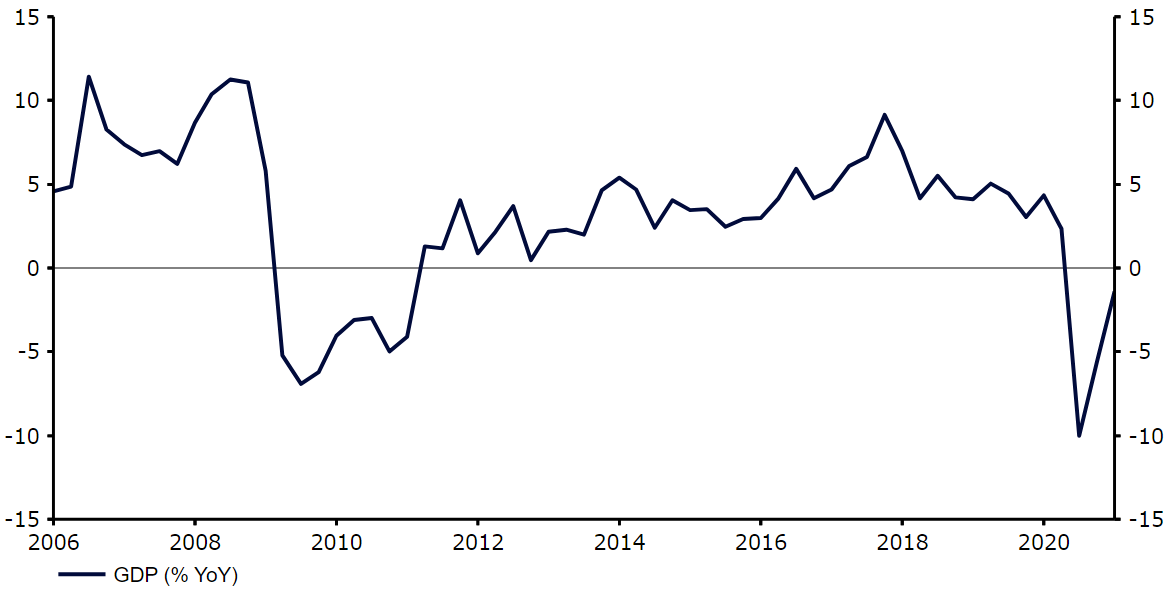

Romania’s government took drastic steps to limit the spread of the virus in 2020. The national lockdown imposed by the government in late-March last year took a significant toll on the economy. GDP growth came in below its long-term trend at 2.4% in the first quarter of 2020, albeit remained in positive territory. The hit to growth in the first quarter was limited by the fact that the harshest containment measures were not imposed until very late in the quarter. In the second quarter, gross domestic product contracted by 10% year-on-year (11.8% quarter-on-quarter). The economy did bounce back in the third quarter of the year as lockdown measures were unwound, posting growth of 5.6% quarter-on-quarter.

On an annual basis activity did, however, remain deep in contractionary territory at -5.6%, ensuring that Romania significantly underperformed its peers. The final quarter did, however, bring a significant surprise as the previously underperforming economy grew by 4.8% from the previous quarter, far outperforming its peers (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Romania Annual GDP Growth Rate (2006 – 2020)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

Both the National Bank of Romania (NBR) and the country’s government have introduced a set of measures aimed at allaying the downside impact of the lockdown measures. To ease pressure on the government, firms and households, the central bank has cut interest rates on four occasions since the onset of the crisis, taking its reference rate down by a total of 125 basis points to 1.25%, with the last cut taking place in January this year. It also introduced other measures, chief among which is its asset-purchase programme that has seen the central bank buy government bonds in the secondary market. The programme’s aim is to suppress bond yields and lower the cost of financing. An increase in inflation since the beginning of the year means that Romania’s real rates have decreased sharply of late, falling to -1.8%.

During the initial emergence of the virus, the government introduced a series of measures to support the economy. The key ones included targeted health care expenditures, wage support for some workers, additional financing to SMEs and modifications to tax measures. While the measures were not very large compared to those introduced in other European countries they have, alongside a relatively recent pension hike, led to a decrease in tax revenues and a deterioration of the country’s fiscal position. Even prior to the pandemic, Romania has been infamous for its comparatively large fiscal deficits, with the deficit-to-GDP ratio standing at 4.3% in 2019. On a more positive note, Romania is set to be one of the biggest beneficiaries of the EU’s €750 billion recovery fund, kicking off this year.

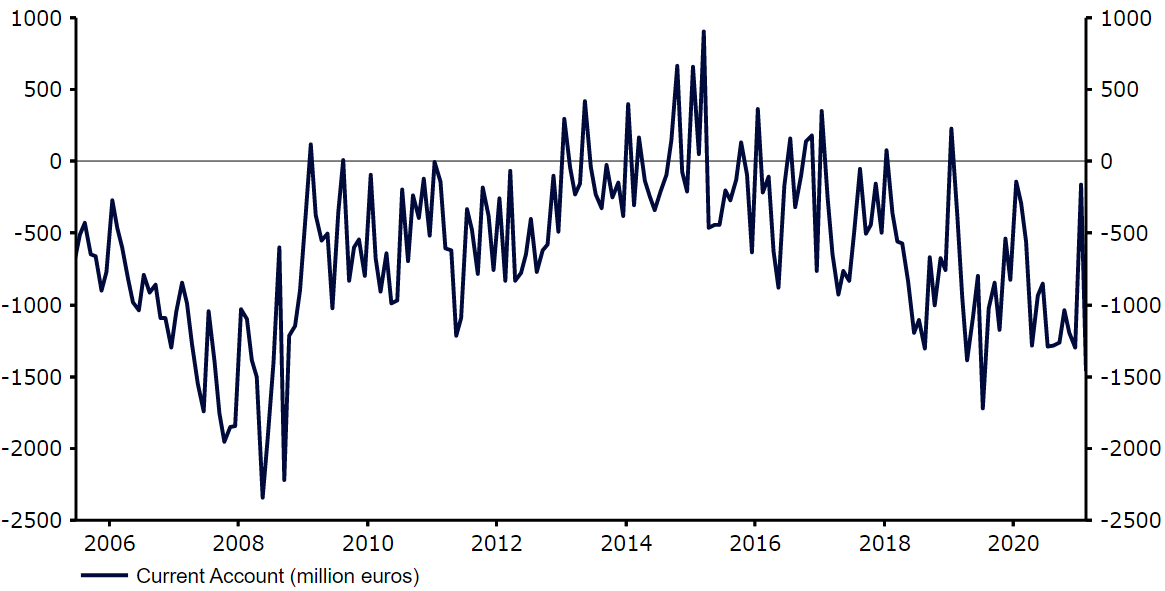

A negative for the leu is that Romania has one of the largest current account deficits among the EU countries. This deficit has deteriorated in the past five years, reaching 4.6% of GDP in 2019, and was similarly negative throughout 2020 and in early-2021 (Figure 20). This imbalance is one of the main reasons why we believe that the leu is likely to remain under pressure versus the euro over our forecast horizon.

Figure 20: Romania Current Account [mln EUR] (2005 – 2021)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream Date: 13/04/2021

Even following the resurgence of the virus in Europe our positive view of emerging market currencies going forward has not changed. We expect most of them to rebound and regain either a portion or all of their losses that they incurred as a result of the pandemic sell-off. The leu is, however, one of the few exceptions. We think that the country’s poor macroeconomic fundamentals, namely the country’s large twin deficits that are unlikely to go away any time soon, ensure that the Romanian leu is likely to remain under pressure even once the global economy gets back on track. We believe that these imbalances have been a key reason as to why the leu has failed to rebound in line with a general improvement in global market sentiment, contrary to its peers.

We think that Romania is also one of the few countries where the risk of rating cuts from the main rating agencies remains high – our view is supported by the fact that all Big Three rating agencies have already cut the country’s rating outlook to ‘negative’. These ratings are important for Romania given that they are all hovering only one notch above the non-investment grade level. Should they drop into junk, some investors will need to force-sell and others will not be able to buy the country’s debt due to restrictions on holding non-investment grade assets. In addition, Romania’s political environment remains one of the most fragile in Europe. We’re hopeful that the country will be able to start reforming its public finances after the pandemic threat abates, although this remains uncertain.

We are of the opinion that the prospect of a significant fiscal boost from the EU will not be enough to offset the negative effects of other factors that are likely to work against the leu, especially given that the country’s real rates have decreased sharply since the beginning of the year. Based on the currency’s past behaviour, and the fact that it remains closely controlled by the central bank, we do, however, believe that the scale of the depreciation against the euro should be relatively contained.

In fact, due to a resilience of the Romanian currency in early-2021, we revised our EUR/RON forecast lower in early-February to reflect a more gradual depreciation, even in the face of political turmoil and a surprise interest rate cut in January. A depreciation of the currency in late-March, which brought the EUR/RON to the 4.92 level, could mean that the leu will be temporarily weaker than we expected, but we feel overall comfortable with our current forecast, especially over the medium- and long-term.